Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

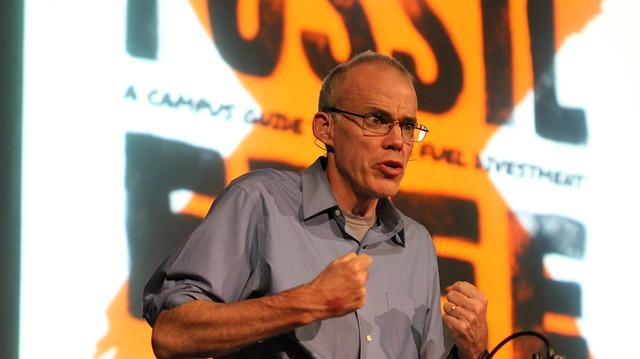

Veteran climate activist Bill McKibben strived to convey a sense of urgency Thursday when he told a group of hundreds that the climate crisis "... will determine what our world is like for everybody who comes after us."

Calling climate change "the defining question of our century," McKibben spoke with Linda Solomon Wood as part of an hour-long interview on Conversations, produced by the Canadian Centre for Journalism and sponsored by Canada's National Observer. Nearly 800 people participated in the live virtual event.

In the wide-ranging discussion, the author, environmentalist and co-founder of 350.org talked about the urgent need to divest from fossil fuels, how grassroots movements can push political leaders to action, and the path for Canada to achieve a net-zero future by 2030 — if the government accepts the fact “it needs to leave carbon in the ground.”

Here's some of what he had to say...

Carbon bombs, climate change and Canada

McKibben once called Canada's oilsands "ground zero of climate change" and a "carbon bomb."

Today, he said, "Canada has a big role to play by virtue of the fact that it has a lot of carbon in the ground — if it chooses to leave it there. If it decides, as it seems to have been committed to for years now, that it wants to dig up as much of it as possible and sell it to people to burn, then it makes the math of climate change much harder."

Atmospheric carbon contributes to rising global temperatures, and McKibben warned of the danger of even incremental increases in those temperatures, noting that an uptick of just 3 C could result in drastic changes.

"If that happens, we won't be able to have civilizations like the ones we're used to. So that's why the fight is on," he added.

In order to prevent further warming, McKibben pointed to recent U.S. climate policy as an example of government taking action to move away from fossil fuels.

"Look at what's happening now south of the border," he said. "The Biden administration actually seems really serious about starting to get things done. They've put John Kerry in charge of global climate diplomacy. On his first day in office, he said, 'We've got to stop building new stuff, new fossil fuel infrastructure, because we're going to have to abandon it in 10 or 20 years.'

"That's just how it works. It's not that the story is complicated here. It's difficult because of vested interests, but the basic story isn't complicated."

As for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, McKibben told Solomon Wood the federal government has an opportunity to limit Canada's carbon output thanks to the price of solar and wind power, which he said has dropped by nearly 90 per cent and is now the cheapest way to produce energy across most of the world.

At a time when anxiety over the energy transition’s financial cost and climate change are at all-time highs, he noted Trudeau has a productive solution within his grasp.

"What I'd say is, (Trudeau is) a lucky guy," McKibben said. "You happened to be in power at the moment when the engineers have given you an extraordinary gift."

'Canada is blessed'

“Canada is blessed with sun and a lot of wind," McKibben told Solomon Wood. "It has extraordinary possibilities to start doing things that will put lots of people to work."

In the lively chat that accompanied the interview, former federal Green Party leader Elizabeth May agreed.

"We absolutely can deliver real climate action," she said. "The provinces are not the barrier. The absence of political will is the problem."

The transition to clean energy is inevitable, McKibben said, and moving toward it quickly would be like “ripping the Band-Aid off.” McKibben referenced a New Yorker story he wrote recently about retraining oilfield workers to service wind turbines, noting the skill sets “cross nicely,” the jobs are easier on workers’ bodies, and they're “not subject to the same kind of boom-and-bust cycle that governs the oilpatch.”

Movements can 'change the zeitgeist'

McKibben, who began his career as a New Yorker Talk of the Town writer, spent part of his youth in Toronto. His father was a journalist who covered Canada for Business Week magazine, and he attended grades 1 through 5 in Toronto — one year behind a boy named Stephen Harper.

"I think I may have talked on the playground to Stephen Harper, but Pierre Elliott Trudeau was an important name in our household growing up," he said.

But while McKibben has "followed young Mr. Trudeau's career with great interest," the activist said he has never talked with him. He prefers to bring about change through movements and activism rather than backroom conversations, he said, adding leaders rarely lead, but, rather, follow the public will.

"In my world view, sitting down with the guys who (are) nominally in charge of things is rarely the way that you make change happen. Change happens when people build movements that change the zeitgeist, that change people's sense of what's normal and natural and obvious. And once you do that, then the little politicians can move into that space and implement things," McKibben said.

"We labour under the idea that our political leaders are leaders. And that's rarely, I think, the case. They perform important roles, but those roles are mostly about occupying space that people have cleared for them.

"My interest always is not in sitting down behind closed doors with leaders. My interest is always in helping build movements that change what's possible. And there's a lot of that going on in Canada."

Divestment movement has diverted trillions from fossil fuels, McKibben says

A total of $15 trillion in endowments and portfolios has been divested “in part or in whole” from fossil fuels, McKibben said.

"When we started, we did not expect it would grow to become what I think is arguably the largest anti-corporate campaign ever," he added, explaining that he and Naomi Klein, who originated the movement, were encouraged by Bishop Desmond Tutu to pursue divestment as a tactic after thinking back to their school days when divestment over apartheid in South Africa became popular.

"One of the ironies of all of this is that, you know, probably Naomi and I are not the first people in the world you would turn to for investment advice," McKibben said. "It's not really our specialty in the world. But as it turns out, we were very prescient about all this."

And, he pointed out, those who have divested have “made out like bandits because the fossil fuel sector has been the worst-performing part of the economy for the last 10 years.”

The divestment movement cuts to the core of how McKibben views the global movement to halt climate change. At first, he said, climate change felt like a nightmare to him, where he could see a monster coming, but couldn’t get anyone else to pay attention to it. He tried desperately to pile up reports and statistics to support his arguments, a tactic he described as a mistake.

“It took me too long to figure out that we were engaged not in an argument, but in a fight, and that the fight was not about data and reason,” he said. “It was about what fights are always about: Money and power.”

Going net zero by 2050

McKibben expressed skepticism about Canada’s plan to hit net-zero emissions by 2050. The focus, he said, should be on 2030. “2050 is not a very interesting year,” said McKibben. “2030 is an interesting year, that’s what scientists have told us. That’s when we’ve got to do most of the work to break the back of this problem, so that means doing big things right now.”

He said 2050 is comforting for CEOs and politicians. McKibben warned against net zero turning into an “elaborate accounting” scheme including tree-planting to offset emissions. He likened this approach to the Catholic Church’s practice of selling indulgences to get followers out of purgatory. “Maybe it works in purgatory, but it doesn’t work here,” said McKibben.

McKibben also said Canada has an outsized role to play in any net-zero plans: It needs to keep fossil fuels in the ground. “The biggest problem is that Canada so far can’t seem to come to terms with the fact that it needs to leave carbon in the ground,” said McKibben.

He referenced Justin Trudeau’s 2017 remark at an oil and gas conference that “no country would find 173 billion barrels of oil in the ground and leave them there.” If Canada chooses to leave it there, “it will play a huge role in helping ward off the worst outcomes,” said McKibben. But if Canadian leadership continues extracting those resources, McKibben said it would use up 30 per cent of the planet’s remaining carbon budget, while Canada accounts for less than one per cent of the world’s population.

“That’s not OK,” he said.

Pipelines and Indigenous leadership

While McKibben is a renowned leader in the fields of environmentalism and climate activism, on Thursday evening he was quick to defer credit for leadership to Indigenous organizers.

“The people who got me going on a lot of this work years ago are First Nations leaders across Canada,” said McKibben, citing Melina Laboucan-Massimo, Clayton Thomas-Muller and Rueben George. He credited Laboucan-Massimo with making him aware of the situation in Canadian tarsands projects. McKibben applied that knowledge during the fight against the Keystone XL pipeline, during which he was arrested for civil disobedience.

Of the Keystone project, into which Trudeau and Alberta Premier Jason Kenney have poured millions of dollars, McKibben was unequivocal: “There’s no way the Keystone pipeline is getting built.”

Given U.S. President Joe Biden’s stated opposition to the project prior to his inauguration, McKibben said Trudeau and Kenney’s inability to predict this outcome “indicates a certain naivete about American politics.”

On pipelines in general, McKibben said, “The thing to always remember about this is: a) if it spills, it’s a disaster; and b) if it doesn’t spill, it’s a disaster.” In practical terms, McKibben said, a spill on the ground is no worse than the successful delivery, refinement and burning of fossil fuels.

McKibben observed Canada is also unique in its state support for and investment in oil and gas projects. “In America, at least the pipelines we were fighting were private corporations,” he said. “In Canada, you’ve taken this to a whole new art, and … decided it would be a good idea to literally put the taxpayer on the hook for building the pipelines.”

McKibben explained that years ago, he decided that since he and climate activists wouldn’t be able to amass the capital to compete with major oil and gas companies, they would have to mobilize the masses.

Question from a 15-year-old

"How does my generation stop the need for greed?" one attendee, James Doyle, asked, adding: "I'm 15 and I'm going to fight."

"Well," said McKibben, "the question is not what 15 year olds need to be doing, because they're doing it. I mean, look, young people are the absolute heart of this fight now. Everybody knows Greta Thunberg ... She's one of my favourite people in the world to work with. She's an innovator in non-violent action in the same way that Gandhi and King were. She's just smart. And there are 10,000 Greta Thunbergs scattered around the planet, and there are 10 million young people following them, and that's remarkable."

McKibben's focus shifted to baby boomers. "Older people have so much political power because they vote and have so much economic power because that's who ended up with most of the money out of the prosperity of the last decades ... so it's going to be really important for people as they age to start taking the legacy that they're leaving behind seriously.

"And the legacy we're leaving behind at the moment is not a good legacy. We're the first generations on this planet that are going to leave the world a worse place than we found it. That's not OK. I think the real answer, James, is keep shouting out so that your grandparents have to answer, so that they understand just how much you want them to be taking the steps that, at this point, they can take to follow the lead of young people. It's a real opportunity right now."

Solomon Wood asked McKibben to look back over his decades of work as a climate advocate and reflect: "What's your view of humanity's ability to really face this and move forward?"

"It's a test of whether the big brain was a good evolutionary idea or not," he said. "It clearly can get us in a lot of trouble. And now we're going to find out if it can get us out. And my suspicion is that the big brain will be important in getting us out.

"But the real question will be how big the hearts to which it is attached are. That is, can we understand a new ethic of solidarity in this world?

"Can we understand that this is an opportunity to turn our back on ... what 15-year-old James was describing as a kind of greed-based economy? Can we take up a care-based economy? Can we make those transitions?

"I think we can," McKibben said. "I think that human beings are capable of it."

What he isn't sure of is whether humanity will act quickly enough.

"It's the reason that I get so crazily mad at the Exxons of the world, because their campaigns of deception and disinformation cost us three decades, and now we have to jam into one decade the work of four," he said. "And it's going to be extraordinarily hard. But what's really good is that it's now translated into these big, broad, massive movements. My mistake as a young journalist was in thinking that we were mostly engaged in an argument and that if we just kept piling up more reports and books and articles and things, eventually the powers that be would do the right thing."

He added: "We would have to mobilize. We're never going to have the money that Exxon has or that TransCanada has or that Enbridge has ... And what's happened is that (through movement building) now that power has begun to balance some, and that's why we're able to at least take this on.

"So being a creature of habit, I would say a good recipe for the coming 10 years would be to do a lot more movement helping and keep up that kind of power building and see what we can make happen and how fast we can make it happen."

Comments