Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

The climate mobilization in Canada, as I’ve written in previous columns, has yet to feel like a grand societal undertaking. Among the bold initiatives that would send such a signal — a Youth Climate Corps.

As young people come to the end of a school year unlike any before, and those in their teens and early 20s wrestle with the prospects of a dismal job market, post-secondary institutions still reeling with post-pandemic realities and, looming over it all, the escalating climate crisis, now would be a very good time to offer an ambitious new opportunity for those looking for something hopeful and meaningful.

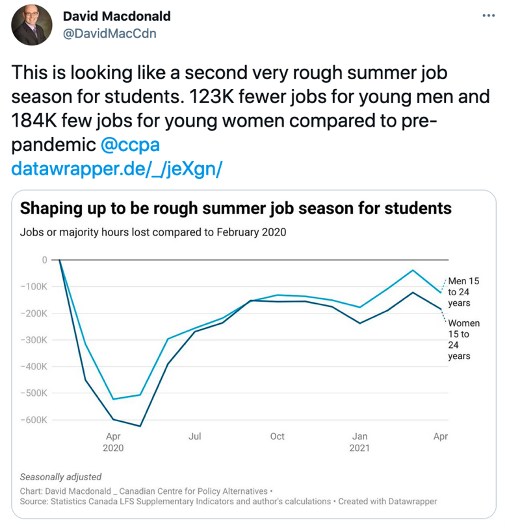

The economic and mental health impacts of the COVID pandemic have been especially hard on young people, and those impacts are likely to have a long lag. David Macdonald, senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, notes the summer of 2021 is looking grim for the youth job market, with 123,000 fewer jobs for young men and 184,000 fewer jobs for young women than in the month before the pandemic.

Generally the last hired and first fired, economist Jim Stanford notes that “26 per cent of workers under 30 lost their jobs in the first two months of the pandemic, compared to 12 per cent of workers older than 30.” The subsequent rebound in employment “has been much weaker for young workers. More than two-thirds of all remaining job losses (relative to pre-pandemic levels) are among workers under 30, even though they account for barely one-fifth of the working age population… This summer the pandemic still rages, but there are no targeted benefits for young workers.”

But it’s not just the job numbers. Stanford worries young people will likely suffer the worst long-term social and economic consequences from the pandemic. “Young Canadians are experiencing an epidemic of suicide, substance abuse and eating disorders that rivals the coronavirus in ferocity; health officials have declared a youth mental health emergency. Disrupted schooling has held back educational progress at all levels, with lasting ramifications for students’ learning and future employment.”

Young people are struggling (not least with the mental anxiety of climate distress). And our leaders can and should step up to help. “An ambitious strategy to help young people rebuild their lives when this is all over is a vital prerequisite for long-term economic and social recovery,” concludes Stanford. “Governments need to think big and move fast to support young workers.”

Agreed. And an audacious Youth Climate Corps — a youth mobilization to confront today’s gravest threat — could be just the solution.

It sure would have been nice if we’d been preparing for this over the last year. Not to mention if the Trudeau government hadn’t made such a hash of potential youth programs with the WE scandal. It is deeply frustrating that a year ago the government opted to contract out the delivery of a bold youth program when the federal and provincial governments already had numerous youth service, training and employment programs in place, perfectly able to scale up if the funding had been made available.

In contrast to the hand wringing of the present, consider how youth signed up in response to a previous existential threat, and how the government encouraged and supported their efforts.

In the Second World War, over one million Canadians enlisted for military service from a population at the time of about 11.5 million, a remarkable level of participation, particularly given what those who signed up were prepared to sacrifice. Of those who went to fight overseas, from all corners of the country and all ethnic backgrounds, the overriding characteristic most had in common was their youth — about 64 per cent of the Canadians who enlisted during the Second World War were under the age of 21.

Back then, when young people stepped up to serve, our government was eager to receive them (even when, in the early years, the readiness of the training programs was still being hurriedly patched together). Today, young people would surely jump at the chance to meet this new generational moment. As the world has begun to confront the climate crisis, the last few years have seen a burgeoning of youth leadership. As in the war, youth are once again mobilizing to secure our collective future. But so far, our governments have failed to create public programs to accept and deploy their energies and talents.

The good news for today is that the crises we must confront call upon us to help and to heal — both society and the planet — rather than to fight and kill.

Canada needs a new youth corps, focused on the helping and healing work required to tackle the climate emergency. Not a compulsory form of youth service, as still exists in some countries, but an attractive one.

The closest such program we have is Katimavik, a federal youth program created under the government of Pierre Trudeau (and at one time chaired by Justin Trudeau) that has been operating off and on since the late 1970s, which has placed more than 35,000 young people into community service volunteer work. But Katimavik is only a half-year program with just a handful of spots available each year. More recently, the federal government initiated the Canada Service Corps, but it, too, is a relatively small program that merely offers short-term volunteer opportunities to young people.

Last year, in the early months of the pandemic, the environmental NGO Wildsight partnered with the City of Nelson, B.C., in the Kootenays and created a Youth Climate Corps (yes, they even used the same name I’m proposing). It looks like an inspiring program that combines climate-related education and field work. But again, it is a tiny initiative, only able to offer a little over a dozen placements.

We need something at a much larger scale. Now is the perfect time to quickly retool these initiatives and launch a new national project.

A large-scale Youth Climate Corps (YCC) could be aimed at young people who have finished their high school education and invite them to spend two years working on projects that seek to expedite our climate transition. Like the military, the YCC would offer room and board and decent pay. The program should be open to all youth who wish, although special efforts could be made to encourage systematically marginalized youth to enlist. And like the military, when they complete their service, they could be offered free post-secondary education or training.

Members of the YCC could be engaged in restoring ecosystems that help capture carbon, responding to climate disasters and enhancing community resilience, and building the new climate infrastructure we desperately need (renewable energy projects, building retrofits, high speed rail and more). YCC youth could also be involved in low-carbon caring work (elder and child care) at the heart of a Green New Deal. The work must not displace other workers, but as there is so much climate-related building and restoring to be done, there is no reason such a program should be seen as a zero-sum game. Rather, it could offer apprenticeship training to a generation of youth in the climate and energy transition jobs of the future.

Such a program could be a win-win — youth would be engaged in meaningful work and gain valuable experience for their future plans and careers, while society gains an eager army of climate warriors helping us rise to the climate emergency.

In the U.S., the new Biden administration, heeding the call of the youth-led Sunrise Movement, has launched a similar initiative — a Civilian Climate Corps — and has asked Congress for $10 billion to seed it. Inspired by the Depression-Era Civilian Conservation Corps (a foundational element of President Roosevelt’s New Deal that employed about 300,000 people), this new program isn’t explicitly youth focused but seems oriented that way. You can read more about what this program could look like here. Or check out this short video Sunrise produced, offering a flavour of what they envision, here. I dare you to watch it and not feel inspired to call for something similar in Canada.

Don’t ask youth to wait. The emergency is now.

If I were 18 today, finishing up high school and contemplating post-secondary studies or some job, I’m fairly sure I’d be wondering: “What’s the point, if the emergency moment is now?”

Why, at this time of heightened crisis, with a civilizational threat again at our doorstep, would we want young people eager to act to wait? In the Second World War, hundreds of thousands of young Canadians deferred their studies, they left their farms, they delayed plans to join the workforce or launch their careers — and instead they enlisted, because the emergency was immediate. Today, a new generation of young people needs a way to meet this moment.

Young people crave a sense of purpose — a desire to believe in something greater than themselves. We all do, of course, but this too often gets squashed out of the older among us as we deal with the daily demands of work and family. That yearning for a sense of purpose is what led many to enlist in the Second World War. It is what American philosopher William James sought to find in a non-destructive cause in his 1910 essay “The Moral Equivalent of War.” James was an anti-war activist but believed people need the sense of meaning, purpose and common struggle that often comes with war. James proposed a form of youth conscription but directed towards something more worthy than war, and he sought examples of events or struggles that could “inflame the civic temper as past history has inflamed the military temper.” To which the climate crisis replies, look no further.

Climate change will be the defining issue facing today’s youth, with profound consequences for their futures, families, communities and careers. How we confront the largest collective action puzzle of human existence will be the story of their lives. We would do well to fully enlist them in the challenge as soon as possible.

Comments

For the most part, I agree with you, Seth. However, your comments about the WE affair are disingenuous. The initiative for a youth corps to help fight the Covid pandemic was first envisioned as a scaled up program under the existing Canada Service Corps. The public service, however, advised that neither the Canada Service Corps nor any other existing federal youth program could be scaled up quickly enough to meet the government’s requirements. Although the time constraints are less binding for climate action (perhaps), your comment that there are presently numerous programs that could be easily scaled up seems to directly contradict this. Do you have any evidence, or is this just wishful thinking, compounded by ignorance?

I fully agree that there should be a programme that urges or assists young unemployed people to find jobs. I much prefer the idea of high school graduates spending a year in the work force before entering a post-secondary education institution. They truly need to see the real world in order to determine what sort of future they wish to pursue. Many work suggestions have been proposed, but for some reason, no one to my knowledge has mentioned a trade. We currently, across Canada, have a severe shortage of trades people. This is an opportunity seeking a place to happen. Young people coming our of high school could learn a trade and be paid for the training. Many may even decide that a trade is preferable to university. I suspect, however, that the greatest impediment to such a proposal is that Canadians still look down their noses at trades. It was true when I was growing up 70 years ago, and it's still true today. Parents want their kids to go to university and push them in that direction, even though many or perhaps most of those kids are unsuited to academia. I recall speaking to two math professors at Waterloo several years ago. They both felt that as many as 60% of university students did not belong in university. So here's an opportunity for productive employment for young people who are currently struggling in the gig economy. Why not seize it? What's wrong with being an electrician, a plumber, a carpenter or a stone mason? Young people can make the world a better place by actually building something rather than just talking about it.