Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

A multinational scientific expedition is set to launch to solve the mystery of what happens when salmon head into the Pacific Ocean and how climate change is impacting both the iconic fish and their marine environment.

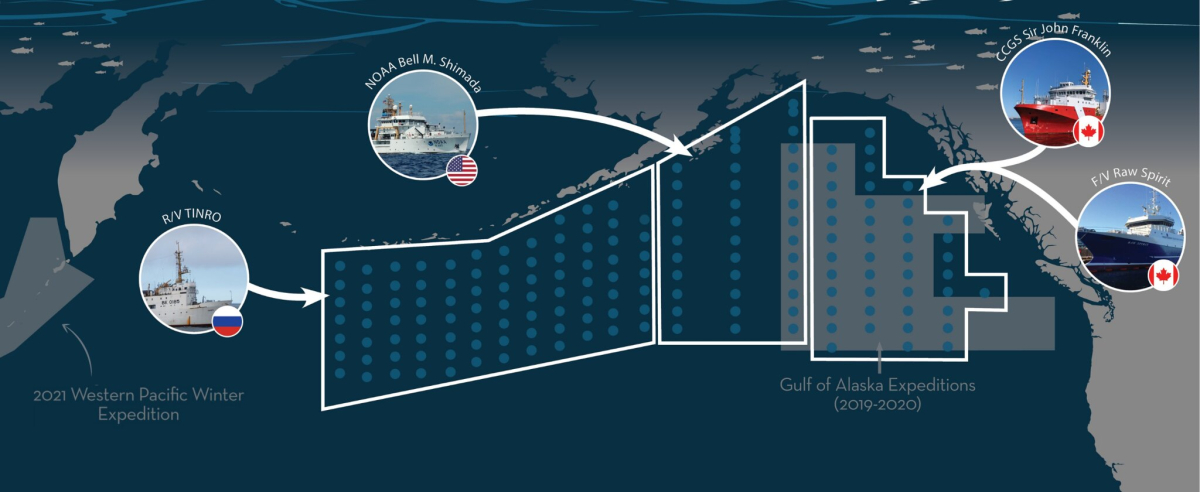

Four vessels and more than 60 international scientists from Canada, Japan, the U.S., Russia and Korea are taking part in one of the largest-ever surveys of salmon in the North Pacific from February to March, said Brian Riddell, science adviser for the Pacific Salmon Foundation.

Science has barely scratched the surface of what is going on with diminishing stocks of Pacific salmon when they head out into the high seas as conditions change with global warming, Riddell said, noting oceans absorb 90 per cent of the globe’s surplus heat.

“This expedition is really important,” he said, adding it will provide a solid foundation for more extensive international research efforts in the future.

“There’s almost no assessment going on in the North Pacific about what (climate change) is doing to fishery resources and the systems in the ocean,” said Riddell, who helped establish the research initiative.

“We have to play a lot of catch-up.”

There’s clearly a general understanding that shifting ocean and climate conditions impact salmon stocks, Riddell said.

“We certainly see the effects,” he said, citing the widespread closures of commercial salmon fishing on the West Coast, and the diminishing availability of the fish for First Nations food, social and ceremonial needs.

But what specific factors affect salmon productivity, distribution or survival need more examination, he added.

The expedition will build on findings from other associated, but smaller-scale, expeditions between 2019 and 2021 — which are all part of the International Year of the Salmon research initiative by the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission (NPAFC).

This winter, four vessels — research boats from Canada, United States and Russia, as well as a Canadian fishing boat for catch surveys — will check out four zones along the B.C. coast, the Gulf of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands.

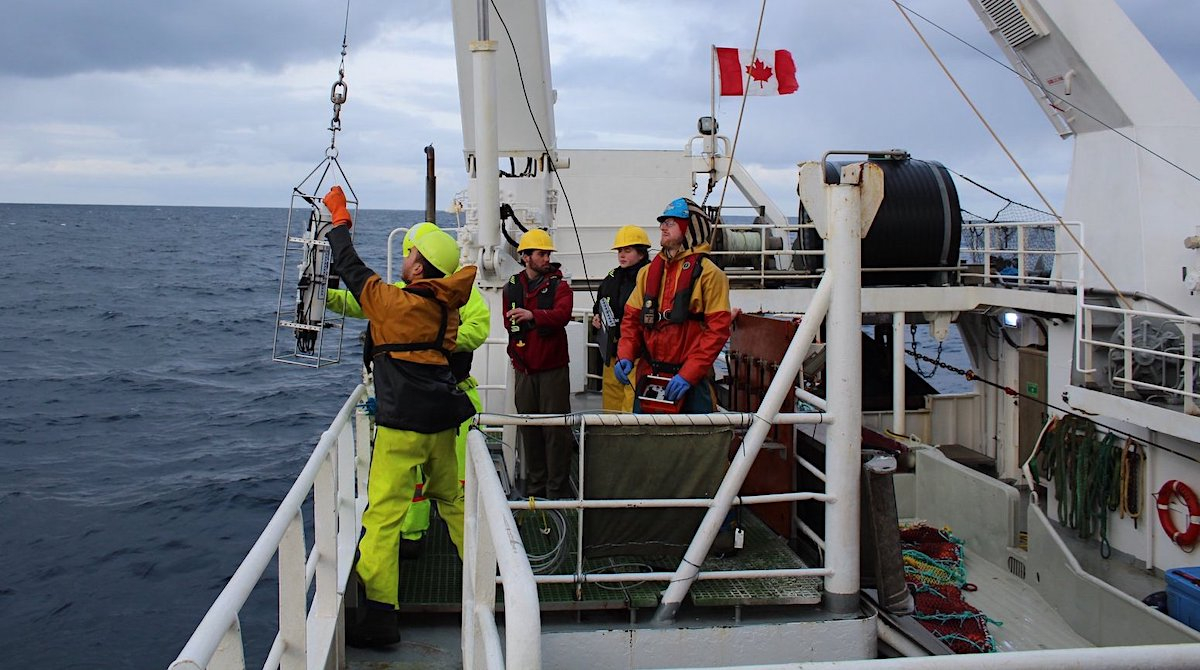

To get a better read on salmon ecology, the boats will use equipment and nets to gather water and biological samples as deep as 1,000 metres at co-ordinated stations 60 nautical miles apart from each other.

The goal is to explore the marine ecology looking for what salmon eat or what eats them — including plankton or large predators such as salmon sharks — while tracking the main objective, various salmon stocks both abundant or threatened.

Novel technologies will also be used, including environmental DNA (eDNA), which examines loose-floating fragments of genetic material to get a wider look at what lives in the ocean even if the creature that left it behind is no longer in the area, said Riddell.

“It means we can take a water sample, we concentrate it and amplify the DNA, and then you can look at the different species that are using the habitat, even though we don't catch them,” he said.

“So we can actually look at the biological diversity in the ocean without killing all the animals we’re sampling.”

And salmon DNA will be used to identify their river systems of origin to try to pin down the patterns of movement for particular stocks through the North Pacific.

The expedition is transformative in nature given the scope and international co-operation and is a model to extend international research even further to understand the ecology of the North Pacific salmon, Riddell said.

“This is the first time that we've done a trans-Pacific survey in probably over 50 years,” Riddell said.

“You can't really study these things unless you study them across large spaces, and a co-ordinated effort is almost essential.”

The end goal is to expand the number of people in the scientific community working together, Riddell said.

“It’s not just about the science, but doing the training, universities recruiting young scientists, and improving communication and building international collaboration between these different countries,” he said.

“That really is the future of being able to understand climate effects.”

Rochelle Baker / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

Comments