For the purposes of this article, we use the term ‘women’ to include people with ovaries and people who identify as women, recognizing that both sex and gender affect vulnerability to asbestos-related illness.

Mesothelioma has long been considered an “old man’s disease” because people working in high-risk industries — like construction, mining and firefighting — were most likely to be diagnosed with the rare, aggressive cancer caused by asbestos exposure decades later. But a new face of mesothelioma is emerging: women under the age of 50 with no known asbestos exposures.

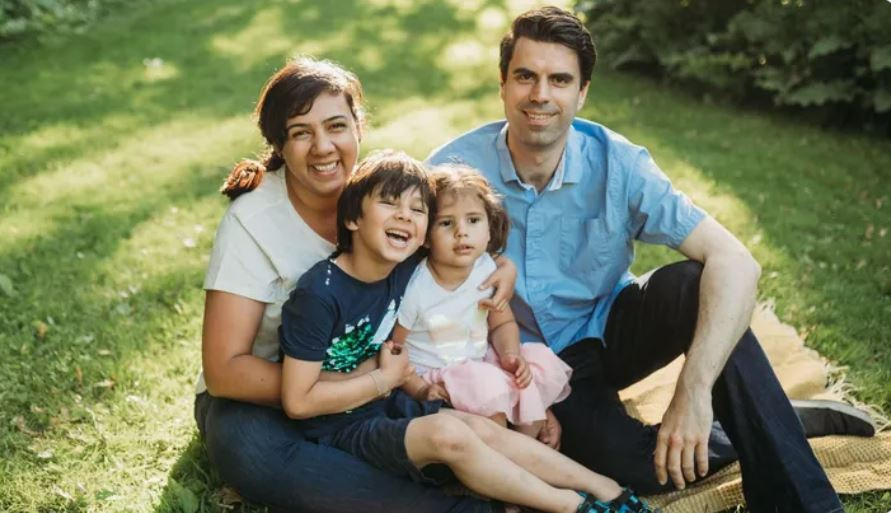

Take Sheila Colla, a 41-year-old racialized woman, associate professor, and mother of two young children. Last fall, Colla was diagnosed with biphasic pleural mesothelioma, which affects the lining of the lungs.

“I grew up in the city of Toronto, I lived in North York and Scarborough. We rented most of our lives, so I never lived through renovations of houses. I just went to really old schools and old community centers here,” Colla explains. “I've been exposed to asbestos somewhere in the city. And I don't know how it happened.”

The truth about asbestos

Asbestos is a mineral that, a generation ago, was commonly used in building materials to make them long-lasting and fire-resistant. Inhaling asbestos fibres can cause mesothelioma, lung cancer, and scar the lungs (asbestosis). Mesothelioma typically develops 15-40 years after asbestos exposure. This, coupled with multiple possible sources of non-occupational exposure to asbestos (including environmental exposures), makes it almost impossible to pinpoint the “where” and “when.”

Asbestos can be found in older car parts, in our roads, and in the building materials of our homes, schools and workplaces (especially buildings constructed before 1990). Asbestos has also been found in Canadians’ drinking water, because the asbestos cement pipes that carry our drinking water are deteriorating. Ingesting asbestos via drinking water may cause mesothelioma in the lining of the abdominal organs (peritoneal mesothelioma); the evidence of potential harm is strong enough that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) considers asbestos to likely be a human carcinogen when ingested.

Talc (the main ingredient in baby powder, also found in cosmetics such as blush, bronzer, and eye make-up) is an often-overlooked source of asbestos exposure. Talc is a natural mineral that often forms in close proximity to asbestos, thus raising the risk of asbestos contamination. In fact, exposure through asbestos-contaminated talc explains many cases of mesothelioma once deemed idiopathic (i.e. no known cause), especially among women.

Regular use of baby powder is common amongst racialized women — but this isn’t a coincidence. Baby powder was initially marketed to mothers for diaper changes. But when studies in the 1950s revealed the health risks of breathing in talc, Johnson & Johnson shifted their advertising focus to young women as a “simple, feminine way to smell clean and fresh” — perpetuating the misogynistic myth that vaginas are dirty — and to Black and Hispanic women, capitalizing on the racist stereotype that women of colour are inherently unclean.

In 2019, the United States Food and Drug Administration ordered a recall of certain Johnson & Johnson baby powder products after testing showed trace levels of asbestos. Johnson & Johnson has been criticized for continuing to sell talc-based products despite knowing about potential asbestos contamination.

“They knew that they had asbestos in their product, and they still sold it,” Sheila Colla explains. “We had baby powder in our house for 12 years — maybe I was exposed that way.” Now, Colla is considering joining others pursuing legal action against the company.

With so many potential asbestos exposure sources, how can we avoid it?

The short answer is, we can’t. The responsibility of avoiding exposure cannot fall on the individual; it is our governments’ responsibility, and they’re not doing enough.

Health Canada introduced regulations in 2018 that prohibit the manufacture, import, sale and use of asbestos and asbestos-containing products. But this ban does nothing about the structures and products that already contained asbestos before 2018, and has some dangerous exemptions that will continue to expose workers and nearby communities. The ban also doesn’t impact the occupational exposure limit for asbestos, even though there is no safe level of exposure and Canada’s limit is 10 times higher than that of the European Union.

Health Canada claims that asbestos in building materials is not dangerous if left undisturbed, and suggests that anyone doing renovations or activities that may disturb the asbestos should hire asbestos testing and removal professionals. But how will that prevent everyday asbestos exposures like walking past (or living and working near) active construction sites?

Despite growing concerns and calls for action, Health Canada refuses to investigate water as a source of asbestos exposure or establish drinking water guidelines. This is because it has determined “there is no consistent, convincing evidence that asbestos ingested through water is harmful to your health,” even if pipe deterioration increases levels of asbestos in drinking water. Health Canada claims that this conclusion is supported by the World Health Organization, but fails to mention WHO’s acknowledgement that lack of data should not stop countries from taking action to reduce asbestos exposure through drinking water, including by replacing asbestos-cement pipes.

Alarmingly, Health Canada does not have to approve consumer products and cosmetics like baby powder before they are sold. Given that Health Canada permits trace levels of asbestos in consumer products, doesn’t regularly test cosmetics for toxic substances (and finds high rates of non-compliance when it does), it is quite possible that asbestos-contaminated talc products are on Canadian shelves as we speak.

Asbestos exposure is an environmental justice issue

Thanks to targeted marketing and eurocentric beauty standards, women (racialized women in particular) are more likely to be exposed to asbestos in talc-containing personal care products. Low-income and racialized communities in the US and Canada are more likely to live in older homes with deteriorating building materials, less able to cover asbestos testing and removal costs, and are often located closer to environmental hazards such as former asbestos mines and landfills containing asbestos-containing materials.

This is environmental racism, a major issue that our federal government has committed to addressing under Bill C-226 (The National Strategy Respecting Environmental Racism and Environmental Justice Act). This law requires data collection on the link between environmental risk, race and socioeconomic status, and presents a vital opportunity for the government to identify populations that are disproportionately impacted by asbestos exposure and address these health inequities. For example, layering a map of asbestos mines over a map of First Nation reserves could help identify communities facing greater asbestos exposure.

Health Canada needs to take concrete action now to get asbestos out of our buildings, drinking water, roads, and personal care products, as well as expand mesothelioma research to include younger people and women.

Colla is currently undergoing immunotherapy at Princess Margaret hospital, and is doing much better than last fall. But her future is far from certain.

“Mesothelioma has a pretty bad prognosis. If the numbers are right, I probably won't be here in a year. I hope they're wrong, because the numbers are based on 70-plus year-old males,” says Colla.

“I was a newly tenured professor at the height of my career. I have two small kids who are very worried about me. I can’t plan more than three weeks in advance. From day to day, I don’t know how I’m going to feel, if I’ll be able to get out of bed or not.”

You can donate to Sheila Colla’s GoFundMe campaign here.

Kanisha Acharya-Patel (she/her) is an intersectional feminist, environmental justice advocate, and public interest lawyer.

Anna-Liza Badaloo (she/her) is a health equity writer, environmental justice educator, and founder of Anemochory Consulting.

Comments