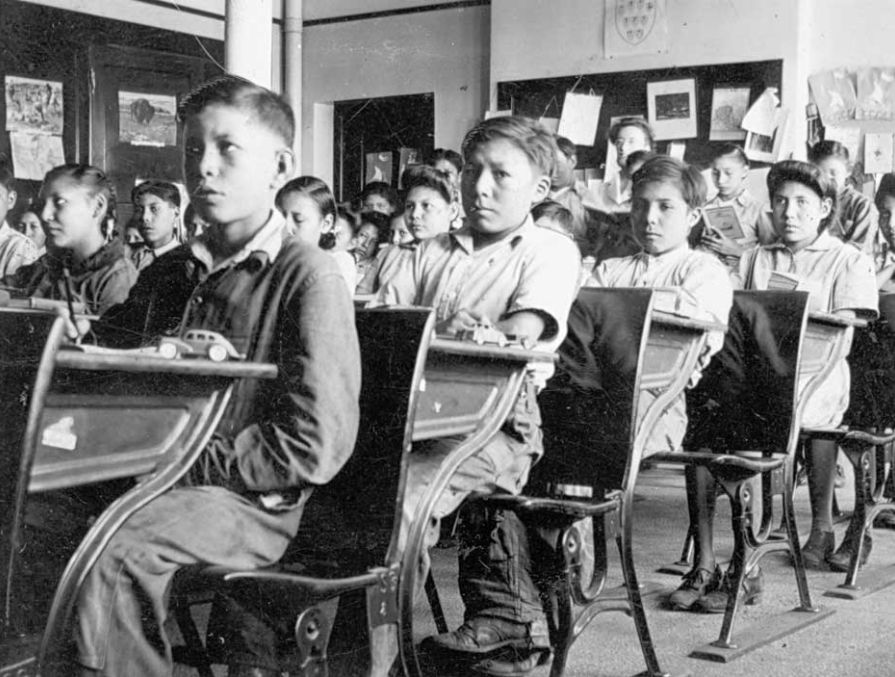

“Instead of the isolation and neglect of the past, a free and equal chance with children in urban centres.” This is the voice of a male narrator in a March 1955 CBC television piece about Canada’s residential schools.

Since that piece aired more than six decades ago, the way Canadians look at residential schools has changed. The federal government’s own examination culminated in the official apology, read in the House of Commons by Prime Minister Stephen Harper in June 2008.

As a newcomer to Canada in 2000, I was astounded at the wide range of views that Canadians possessed whenever residential schools were mentioned. Some pointed the finger at the federal government, the clergy or both. Others staunchly defended the policy and described two solitudes that simply had to be forced to work together. Another person sounded like an adapted version of the 1955 CBC report. Residential schools, in his view, ultimately afforded a neglected group of Canadians the chance to compete with more privileged ones.

The first place where we usually learn about historical wrongs is school. When looking at possible ways to survey how Canadians feel about residential schools, I settled on one sample source (adults who attended elementary and/or high school in Canada) and three simple questions: were you told about residential schools during your time as a student, what were you told and how do you feel about them now. In October, 812 adults responded to the survey.

The first surprise came in the massive differences related to the simple notion of even discussing the topic at hand. Almost half of respondents (47 per cent) say they did not learn about residential schools in any classroom. This includes majorities of those aged 35-to-54 (54 per cent) and those aged 55 and over (61 per cent). Among those aged 18-to-34, the proportion that did not discuss the topic drops dramatically to 21 per cent.

Millennials are more likely to have heard about residential schools during their time as students and to have started looking at the issue in elementary school. When analyzed by region, the data suggests that two school systems were far behind in discussing residential schools in the classroom. More than half of residents of Alberta (56 per cent) and Ontario (54 per cent) said they never reviewed this topic at their own schools.

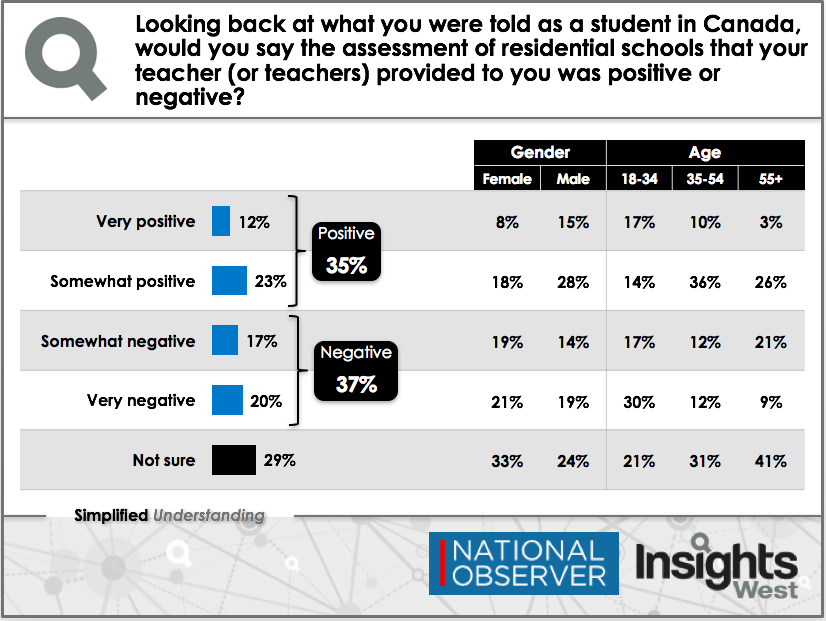

When asked about what they were told about residential schools by their teacher (or teachers), 35 per cent respondents say the assessment that was provided in the classroom was “positive”, while a similar proportion (37 per cent) recall it as “negative”.

This time, it is Generation X that shifts the numbers, with 46 per cent of respondents aged 35-54 saying their teachers spoke about residential schools in a “positive” light, compared to 29 per cent for those aged 55 and over and 31 per cent for those aged 18-to-34.

Almost half of Millennial respondents (47 per cent) say they were taught in school that residential schools were bad. According to the Truth and Reconciliation commission, around 4,000 Indigenous students died in residential schools, which were operated from the 1870s to 1996, and sexual and physical abuse in these schools was rampant. Teachers were more likely to look at residential schools positively in Quebec (45 per cent) and Atlantic Canada (43 per cent), while British Columbia was at the lowest end of the spectrum: just 17 per cent remember their teachers speaking positively about the issue.

There is a significant difference in what students remember hearing in their classroom and their current assessment of residential schools. More than half (53 per cent) say their own personal assessment of residential schools is now “negative”—a proportion that includes 78 per cent of British Columbians, 62 per cent of Ontarians and 61 per cent of Albertans.

There is a noticeable generational gap that cannot be understated. Millennials, who heard more about residential schools in their classrooms, do not deviate too much from the assessment they received from their teachers (47 per cent say their teachers told them residential schools were bad and 49 per cent say their own view currently is “negative”.).

This research has allowed me to review how the topic of residential schools was addressed in Canada’s classrooms—and the fact that, in some cases, it was not addressed at all. Most older Canadians have become aware of the issue and view it in a more negative light now, even after one-in-four of them state that the “official story” delivered by their teachers was different than the reality they are now able to grasp, decades later.

Comments

Being in my eightees I can say without a doubt that the entire subjects of aboriginal education or the abhorrent Doctrine of Discovery were never mentioned in any classes I attended. It wasn't until I was 77 years old that my education was startingly broadened by my reading on the Doctrine of Discovery through a pamphlet published by the Seventh Generation Fund for Indigenous Peoples, Inc.. For others in my age category who believe you learn something new every day I highly recommend this as a starting point to all the exploitative behaviors of governments ever since then. It is puzzingly titled "A Red Paper" which reveals nothing about the time bomb inside it. But its subtitle reveals its evil contents very succinctly, "The Human Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Doctrine of Discovery: Medieval Christian Theology at the Heart of Modern International Policy", and clearly reveals the rationale for the capitalistic subjugation of indigenous cultures around the world. If you read it thoroughly, you, like me, will be appalled that the whole continuing mess was initiated by a religious proclamation given by Pope Urban II in his speech at Clermont in 1095 . Almost four hundred years later, in 1492, it led to led to Christopher Columbus stating, "I do not wish to delay, but to discover and go to many Islands to find gold". And boy, did he ever! And the rampage since then has swept the world. Not until the United Nations proclaimed the "United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples" (UNDRIP) as a fundamental principle of all humans has there been even an adjustment of international greed and theft of resources. But UNDRIP still has to become the law of all nations before our present social and economic systems can be torn apart and rebuilt in a harmonious manner.

Even though I spent my entire working life as a school teacher I was totally unaware of the doctrine upon which European Christian civilization rationalized their divine right to dominate the world.

We get so soon old and so late smart.

Thanks very much for your insightful comments re: education/lack thereof on this issue, Ian. It's interesting to think how something a lot of under-35 people think of as common knowledge isn't depending on the generation.