The new year is a time of reflection for many, a time to consider the trials of the past and the solutions of the future. With 2018 behind us — filled with wildfires, floods, droughts, and climate negotiations — we start 2019 looking up, with a climate deal entering into force that can change the course of our warming planet.

The Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol carries the promise of nations to phase down the use of powerful climate-warming greenhouse gases by more than 80 per cent over the next 30 years. These hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs, are used in our refrigerators, air conditioners and other cooling products. Replacing them with less harmful chemicals could avoid up to 0.4°C of global warming by the end of the century.

The amendment expands on the Montreal Protocol, adopted in 1987, perhaps the most successful international treaty the world has ever known. Universally recognized by 197 parties and its guidelines widely implemented, the Montreal Protocol reversed the hole in the ozone layer by phasing out substances that cause ozone depletion.

The international agreement made the very real threats of ozone depletion seem like a distant memory. There is already a whole generation for whom the hole in the ozone layer is nothing more than some old-fashioned reference, much the same as a world with dinosaurs and a life before Wi-Fi.

But while celebrating our joint efforts and ultimate success, the world has to now brace itself for a new climate reality: in 2018, global carbon dioxide emissions rose again after several years of stabilization, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recently warned us that we only have until 2030 to hold the increase in average global temperature to 1.5°C.

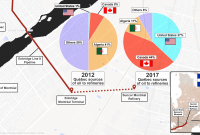

With economies growing in some of the hottest places on earth, there is no avoiding that both the need and access for cooling is rapidly growing, especially in Asia and Africa. The sweaty reality is that of the approximately 2.8 billion people living in places with average daily temperatures above 25°C all year, only eight per cent currently have an air conditioner in their home. By 2050, around two-thirds of the world’s households could own an air conditioning unit.

All this means that the energy consumption of the cooling and heating sectors could surge as much as 33 times by 2100. If this power comes from fossil-fuel sources, it contributes to climate change, which in turn increases global temperatures and the need for cooling. Breaking the vicious circle of rising temperatures and increased demands for cooling takes nothing less than the joint action that yielded the great success of the Montreal Protocol.

With Africa at the forefront on this projected rise in demand for air conditioning, it is only fitting that the new amendment was agreed in the very heart of the continent. Rwanda hosted the negotiations in its capital and Mali became the first country to ratify the document, which came into effect on January 1, 2019.

The Kigali Amendment puts countries in Africa and Asia ahead of the curve as the world moves into an insecure climate future. It gives governments and the private sector the opportunity to embrace new opportunities for sustainable refrigeration and air conditioning, and prioritize sectors and technologies that do not use HFCs, right at the moment as the demand for air conditioning is about to see a sharp increase.

As we look ahead at what 2019 will bring, the new deal will allow all countries to take stock of what is needed to keep global warming in check, and move forward with all the agreements and support on how to manage our new climate reality firmly in place.

Joyce Msuya is the acting executive director of UN Environment

Comments

Justin is doing his best to please the UN. The rest of us?

The more important question is, is Justin committed to saving the planet so that future generations have somewhere to live?

What new deal? Gotta link?

The UN stands for united nations. Are they?