Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Most of us think about Pinterest as the place to go for recipes and craft inspiration, but a new analysis suggests the platform may have been an important source of extreme, hyperpartisan political content during the federal election, much of which was promoted by the platform’s own algorithm.

The analysis, conducted by researchers at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRL), found that after clicking just one anti-Trudeau post on Pinterest, the platform’s algorithm quickly steered users into a far-right ecosystem flooded with disinformation, conspiracy theories and inflammatory memes.

Users didn’t have to “like,” share or save a single post for the algorithm to start recommending far-right propaganda; they simply had to click on one partisan meme, and the algorithm took care of the rest.

The study concludes that, through its algorithm, “Pinterest may contribute to the dissemination of extremist memes as recommended popular items on its app.”

The findings are particularly important given that Pinterest is the second-most popular social media platform in Canada, accounting for 22 per cent of all traffic from Canadian social media users, according to the web analytics company StatCounter.

Despite its popularity, Pinterest is often left out or glossed over in discussions about mis- and disinformation on social media. Yet according to the DFRL researchers, as election day approached, the platform increasingly “became a repository for meme-based political smear campaigns.”

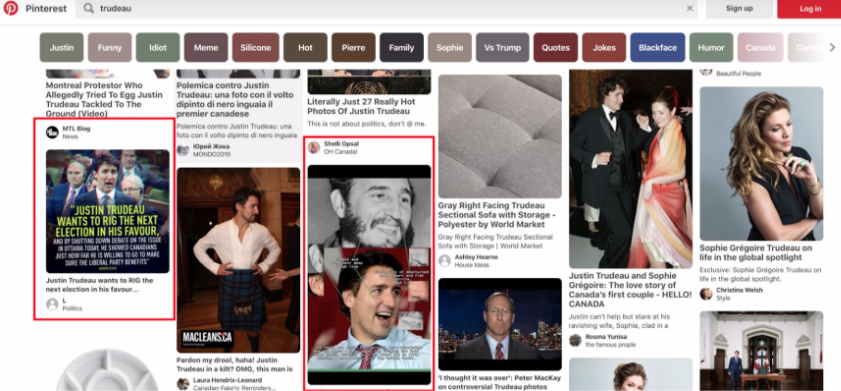

To get an idea of whether and how Pinterest’s algorithm would promote this hyperpartisan content, DFRL research associate Kanishk Karan and visiting research fellow John Gray started by performing a simple search for the keyword “Trudeau.”

The initial page of results returned a range of posts, including two explicitly anti-Trudeau memes near the top of the results. One of the memes claimed that Trudeau was trying to rig the election, and the other promoted a conspiracy theory that Trudeau is the son of Fidel Castro.

After clicking on just one of the anti-Trudeau memes, Pinterest recommended a flood of other anti-Trudeau content, effectively steering users into an echo chamber of far-right conspiracy theories and disinformation.

Despite being a source of disinformation and conspiracy theories, memes are often tagged as humour, Karan said, so they tend to slip under the radar of social media filters.

“Disinformation is embedded in these memes, but they’re being promoted by Pinterest’s algorithm,” Karan told National Observer. “When you’re consuming these memes, it shapes your opinion about the subject.”

Furthermore, the algorithm didn’t stop at anti-Trudeau content. After clicking on just two anti-Trudeau memes, users were steered toward a “far-right meme ecosystem” that encompassed topics ranging from climate change to immigration to feminism.

In a second round of research, DFRL confirmed its findings by having someone who had never used Pinterest before create a new account. As required by the platform, the individual selected five topics of interest (“notionally unrelated-to-politics”), and in the process of doing so, clicked on one anti-Trudeau meme. After logging out and then logging back in, the user’s homepage was flooded with anti-Trudeau memes, based on a single click on a single meme.

While this study focused on Trudeau-related content, it also found similar results for a search for the keyword "Trump" from a blank Pinterest profile. The findings revealed a tendency for Pinterest to promote hyperpartisan content, including both far-left and far-right content, and to narrow future recommendations based on the user's first few clicks.

In other words, while Pinterest’s algorithm was determining recommendations in part based on a user’s own behaviour, it was also restricting users’ options to increasingly narrow choices and increasingly extreme content, creating a vicious feedback loop.

This phenomenon, described as algorithmic confounding, can ultimately shape how people perceive the world by filtering out contrary viewpoints and pushing users towards more extreme, polarized positions.

This produces much more insidious effects that are difficult to measure, yet may have huge implications for political discourse and democracy more broadly, Gray told National Observer.

“We have to start asking ourselves how the algorithms are affecting and framing and having an influence on what we’re seeing,” Gray said. The memes themselves are just manifestations of the algorithms, “but what we should be looking at is how the algorithms are influencing what we’re seeing and how we’re seeing it.”

With the rise of social media, political memes have become an increasingly prominent part of our political discourse, yet visual platforms remain understudied and relatively poorly understood, Gray said.

“We’re failing ourselves in this conversation of understanding the visual component of the web,” he said. “What this comes down to is, we’re really handicapped in terms of access to data.”

So could memes like these influence voters in the federal election? According to Gray, we don’t know for sure and the data to answer that question are not readily available.

While the federal government says there was no election interference that met the threshold for public reporting, this study shows there are many avenues of influence that we may not even be aware of — yet. This includes possible foreign interference, Gray said, noting that memes make it even easier to obscure the original source of content.

“Just because you don’t see the evidence, doesn’t mean something isn’t going on,” Gray said. "We’re really handicapped in terms of research and this is why we really need some good quality open source investigation."

This type of research is slow, he added, but "it's a really vital part of the story."

Comments

Excellent informative article thanks for writing. As mentioned, I never think of Pinterest in the context of the fake news challenge.

This is great research, but it drys out for a follow-up article based on a discussion of these results with Pinterest.

"cries out"