Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

"We're not the problem. We can throw all our car keys in Halifax harbour, turn down the heat, turn off the lights, walk around naked in the dark eating organic beets and it won't make a difference."

- Peter MacKay, Conservative Party leadership hopeful, February 2020 as reported by CBC

If Peter MacKay is to be taken for his word, Canada – along with about 185 other countries – has no relevance in the global struggle to abate the climate crisis.

Despite the fact that Canadians are increasingly demanding climate action, as evidenced by the ongoing protests surrounding the Coastal GasLink pipeline, the Teck Frontier mega oilsands project and the vigorous debates about climate in the 2019 election, the argument that Canada is just a bit player in terms of global greenhouse gas emissions is pervasive. The blame for global warming lies elsewhere and therefore Canada should not be responsible for significant mitigation costs, so the argument goes.

One of the most common excuses used is to point a finger at other large emitters, particularly China and India: “What about China and India? They are far worse than us. Why should we do anything when China and India’s greenhouse gas emissions are growing?”

And Peter MacKay is not alone in his casual dismissal of Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions; the same finger-pointing style of excuse has been voiced by several other high-profile politicians:

“We can shut down our economy tomorrow morning and within a matter of weeks China would replace all of our emissions.”

- Andrew Sheer via his Campaign’s Communications Director on Twitter in September 2019

“This [NDP plan to shut down coal power in Alberta] makes no sense in a world that is planning to build some 2,300 coal-fired electricity plants around the globe.”

- Jason Kenney via his Facebook page in November 2016

"Other countries’ emissions for the most part are going up. World emissions are going up. Canada’s have not been going up.“

- Stephen Harper in December 2014 CBC report

And these arguments aren’t just made by politicians, they are oft repeated in major Canadian news outlets, particularly in the comment sections.. But are China and India the real problem or is this just a tactic of climate delayers designed to distract attention away from Canada’s own responsibilities?

To better inform this analysis, a few facts about the CO2 emissions of China, India, Canada and a few comparable countries will be useful.

Share of global CO2 emissions by country, 2018

CO2 emissions per capita by country, 2018 (tons/person)

Clearly China is the country emitting the most CO2, which has been the case since 2005, when it surpassed the United States. India is also a large emitter, with about half the CO2 emissions of the USA in 2018. Canada represents only a small share of global emissions but is among the leaders in terms of emissions per capita. Emissions from China and India have been growing while emissions from the EU, the United States and, to a lesser degree, Canada have been declining.

It is also important to look behind the relatively recent past that coincides with India’s and China’s rise to economic prominence and to account for emissions throughout all of industrial history. As shown below, the United States is responsible for the most historical emissions, but China is catching up.

Cumulative historical CO2 emissions by country, 1750–2018 (gigatons)

Both India and particularly China stand out in the emissions data and are therefore worthy of a deeper analysis. But it is already clear that India is far behind many other countries in terms of responsibility for the global climate crisis.

India

According to IMF statistics, Canada’s GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power is 6.3 times that of India while emissions per capita in India are already 10 times less than in Canada. Furthermore, India has been a leader in renewable energy development. It was a pioneer in wind, with a total of 35 gigawatts of wind power cumulatively installed through 2018, good enough to rank India fourth globally and produce about four per cent of the country’s electricity.

As a low-income country, India was installing significant amounts of wind power before many rich nations; for example, it reached 1 GW of installed wind power capacity seven years before Canada did. The country is also becoming a solar energy super power: it has ranked no. 2 or 3 in new solar installations globally over the past several years, and as of the end of 2018 cumulatively installed almost 27 gigawatts of solar power, the fifth most among all countries. As of the end of 2018 solar and wind combined to generate about 6 per cent of India’s electricity.

According to the Climate Action Tracker, India is the only G20 country whose current policies are compatible with the Paris Agreement target. Canada’s policies have been rated either highly insufficient or insufficient. It’s therefore a bit rich for people in Canada to demand that India take more action before we get serious about reducing emissions. It is also interesting to note that people demanding India “take action” usually don’t lump the United States into their comment, a country with three times India’s nominal emissions but only one-third of the population. The idea that India needs to act before Canada strengthens its own climate ambitions is absurd.

China

China is the world’s largest annual carbon emitter by far. In addition to its annual emissions, the country has emitted the second most greenhouse gases cumulatively – behind the United States – and recently surpassed the European Union in emissions per capita. Clearly, if humanity is going to address its carbon problem, China must play a major role. What is driving China’s emissions growth? What are they currently doing about it? Is there anything that Canadians can do to have an impact?

The largest contributor by far is China’s coal industry, which represents about three-quarters of China’s emissions and produces coal primarily for electricity generation and for steel production. Also significant are oil for transportation, cement production and gas for electricity generation.

But it’s also true that China has significantly reduced the share of coal in its electricity mix.

Coal electricity generation in China 2010-2018 (terawatt hours)

And even though new coal capacity is being installed, usually as a result of local political support, overcapacity is leading to low plant utilization rates and financial difficulties for Chinese coal generators.

Renewables in China

Part of the reason for the low plant utilization rates are wind and solar power, which have priority access to the grid and now generate electricity at lower costs than coal plants in China (and most other places around the globe), undercutting the fossil-based generators. Thanks in large part to strategic government support, China has developed the world’s leading solar industry. In fact, China is so dominant that it is clearly now the central photovoltaic (PV) technology hub of the world: nine of the top 10 PV cell and module manufacturers globally in 2018 were majority-Chinese according to pv-tech.org. This technology and supply chain ecosystem constantly innovates and competes, driving down the costs of PV globally.

Although Chinese companies do not supply technology to the rest of the world’s wind projects on the same scale as they do for PV systems, China is still the largest individual wind market in the world in terms of generating capacity installed.

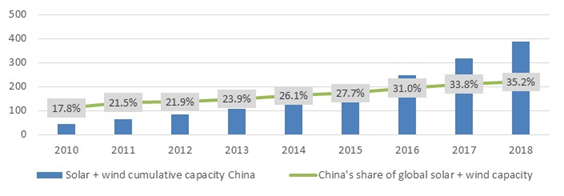

Wind and solar made up about 8 percent of China’s electricity generation in 2018, which is a greater share than that of Canada and of many other developed countries. Through its support for renewable energy generation in general, China has evolved into the renewable energy leader of the world, with about 35 percent of all wind and solar power generating capacity in the world installed there.

Cumulative solar and wind installations (GW) in China and share of global installations 2010-2018

Furthermore, the investment by China’s government and industry in large-scale manufacturing and PV R&D has led directly to dramatic cost declines and significant advances in technology that have been the primary drivers for greater adoption of solar energy generation globally. A significant part of the current global PV energy boom, which has seen cumulative installed solar capacity grow more than 25-fold from 2010 to the end of 2019, can be attributed to China’s support of the industry.

Electric vehicles

A similar upward trend can be observed for electric vehicles in China. The country is the number one EV market in the world and has set a strategic direction to become a major EV supplier to the rest of the world. Since 2015, easily more than half of global EV unit sales have been in China. In addition to personal vehicles, China has been the world’s dominant adopter of electric buses.

Annual electric vehicle sales (thousands of units) in China and share of global sales 2010-2018

About four percent of new vehicle sales in China are electric, a rate that very few other countries have reached to date. Is it conceivable that Chinese companies could drive global road transport electrification over the next decade the way they have contributed to solar growth globally? Only time will tell, but as of now Tesla is playing the leading role outside of China.

When it comes to electric busses, China appears to be in the driver’s seat, as the country boasts an astounding 421,000 out of the world’s 425,000 electric busses, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. This represents a savings of over 200,000 barrels of diesel per day. Thanks to development in China’s thriving home market, Chinese companies are already exporting busses to public transit agencies around the world.

Emissions trading plan

The Chinese government is currently in the process of implementing the world’s largest emissions trading scheme, initially planned to cover large emitters in the power sector. As reported by International Carbon Action Partnership, the Chinese government plans to roll out the scheme nationally in 2020 for the power sector. Almost all coal and gas-fired power plants in the country will be covered under the program. Over the following five years, the government plans to expand the program to cover eight energy-intensive industries including petrochemicals, chemicals, building materials (including cement), iron and steel, non-ferrous metals (such as aluminum and copper), paper and civil aviation.

Unfortunately, the government is planning intensity-based caps (emissions per unit of energy produced) as opposed to hard emissions caps, which means emissions could theoretically rise if growth in output outpaces gains in efficiency. This mechanism would actually be similar to the intensity-based emissions regulations for large emitters in Canada, introduced by Justin Trudeau’s Liberals, which ensure large industrial emitters will pay a lower carbon tax than you or me. Furthermore, cap-and-trade systems require aggressive caps to be successful, and over-allocation of allowances could result in low, less effective carbon prices. Despite the limitations of the proposed Chinese emissions trading scheme, it will add another cost on to coal power plants, many of which are run by companies already struggling financially. There can be little doubt that, if implemented effectively, this program will be the beginning of the demise of coal power generation in China.

China’s survival depends on it ramping up action

China has recognized it is highly threatened by the effects of the climate crisis. One of its primary economic hubs, Shanghai, is particularly at risk of being permanently flooded within this century. A recent paper estimated that the cost of flooding to Shanghai’s residential buildings alone will be about US$87 million per year going forward. This risk is multiplied across the numerous coastal cities in China and combined with increasing water scarcity and desertification inland to generate an enormous threat to the country. These threats explain why China has spent so much money supporting renewable energy and electric vehicles. The country has had a major impact on the global renewable energy boom, but there is still a great deal more that needs to be done.

Clearly China is not doing this for charity. It is one of the countries that will be severely affected by global warming and it has much to gain as the supplier of clean technology to the world.

Conclusion

So what about India and China? If we all matched Indian emissions, the world would be set to reach the Paris Agreement goals. In the case of China, those that bring it up as a major factor in addressing global warming have a point. Though the country has made major contributions towards renewable energy and electric vehicle growth globally, it still needs to accelerate its coal exit if we are to stand a chance to deal with the climate crisis. This article is not meant to absolve China of its climate responsibilities – it is true that if China does not get more aggressive with its climate policies, then humanity as a whole has little chance to mitigate the climate crisis. However, the same result will ensue if high-emitting countries like Canada are unwilling to dramatically reduce their emissions.

Moreover, some of China’s emissions can be attributed to power production that is dedicated to manufacturing goods to be sold in rich countries like Canada. Canada has imported about CAD 43 billion worth of goods from China from January through November 2019 according to Statistics Canada, making China our third largest trading partner behind the United States and the European Union. Citizens that are concerned about the impact of China’s CO2 emissions may advocate for including a carbon border adjustment tax in our trade rules or consider avoiding the purchase of Chinese-made goods in favor of goods produced locally or in other countries with a lower climate impact.

Going back to the first chart presented, it should be clear that blaming China and India is not a solution. Even if both countries were to magically reduce their emissions to zero overnight, other countries still represent about 65 percent of global emissions! The fact that China and India have high emissions does not change the fact that Canada needs to act.

Countries with the same emissions as Canada or less represent about 30% of global CO2 discharge – should they all follow the same line of argument and delay action until China has “sufficiently acted,” a conveniently unquantifiable yardstick? Every country needs to aggressively move to reduce emissions and those that do, can put more pressure on high-emitting countries to follow.

Finally, the average Canadian has no influence on Chinese politics and therefore, saying “what about China?” does not provide for any obvious course of action. Getting people to question why we should do anything when “everything depends on China” is a line of argument employed to delay meaningful climate action and to sow the seeds of doubt in the Canadian population that climate mitigation legislation is useful.

The more useful question would be, “what can we do to reduce our emissions and what can our government do to increase pressure on China – and other high-emitting countries?”

Comments

Great article James!

Thank you for providing us with a better international perspective on the regulation of emissions. I always react when people talk about emissions per capita. As a stand-alone figure, it can be deceiving. Every economy has a demand for sufficient (but not wasted) energy. Your article suggests to me that the common goals should be a figure that represents clean energy production as a percentage of total energy production, although that would include wasted energy. That way China and Canada would be working toward the same goal, 100% clean energy, regardless of the size of the economy or the population. As the economy grows, the demand for energy grows. It must be met with clean renewable energy only in order to increase the % toward 100.

A Question, not a Comment

If China is the largest producer of solar panels, what % of clean energy does it use to do this?

Good question. You would need to look at each production facility/company on a case-by-case basis. What is the grid emissions factor in the region of the facility? Does the company use renewable electricity? But I guess what you're really getting at is the life-cycle emissions of solar PV vs. traditional electricity generation methods.

Here's a study from the National Renewable Energy Lab (somewhat outdated) that estimates the lifecycle GHG emissions from solar PV:

https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy13osti/56487.pdf

They conclude that PV power emits about 25 times less CO2e per kWh generated (40g/kWh) than coal over the entire life cycle. Also, keep in mind PV module efficiency has improved about 30% since the time of this study and silicon use per module has been reduced by about 50%. This implies that in the meantime, the life-cycle emissions of PV per kWh generated has likely halved and it will continue to go down as efficiency continues to improve and more renewable energy is added to the grid.

Here's another presentation that compiles some good info on the energy payback of solar PV, if you are interested (the energy payback time is about 1-2 years depending on the location of the final project - the sunnier the location, the faster the energy payback).

https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ise/de/documents/publications…

"Countries with the same emissions as Canada or less represent about 30% of global CO2 discharge – should they all follow the same line of argument and delay action"

Only 4 nations individually account for more than 3% of global GHG emissions (2015). Together those 4 nations account for 51.1% of global emissions (2015).

Together the other 193 nations account for 48.9% of global emissions (2015).

Exempting Canada and other lesser national emitters leaves nearly half of global emissions untouched.

*

Around the world, in every province and state, people make the same fallacious argument. Almost all nations are small emitters (<2%).

Unless smaller national emitters do their part, global targets remain out of reach.

*

"All nations contributing less than 2% of emissions are, cumulatively, more important than India or China. It absolutely does matter that these nations reduce their emissions." (Willem Huiskamp, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research)

*

Small groups of people everywhere account for only a fraction of the global problem. It's a fallacy to conclude that their collective contribution to the solution does not matter.

Collective problems require collective solutions.

If everyone counts themselves out of the solution, no one will take action.

*

All the small sources around the world add up to 100%. If every person and every industrial project argues that their emissions don't matter because they are a small fraction of the total, no one will reduce emissions.

"Yet Canada is only 1.6% of the world problem."

Do you pay your taxes? Why bother? Your individual contribution is much less than 1.6%. Surely the govt won't miss it.

Do you vote? Sign petitions? What can one vote or signature possibly matter? Everybody may as well stay home.

Ever taken part in a tug-of-war contest? Did you drop the rope, wish your team well, and walk away? After all, what can one person do? If everybody on your team thinks that way, what happens?

*

It's not valid to compare large groups of people with small groups (except by using per capita stats).

You can't compare China's emissions with Belgium's. Or Cardston's, Calgary's, and Canada's.

The average Canadian's carbon footprint is more than twice that of the average Chinese and 8x that of the average person in India.

How can we ask them to tighten their belts when our emissions are far higher?

The fact that large groups of low emitters have greater total emissions than small groups of high emitters does not give high emitters a free pass — or excuse them from their greater responsibility for the problem.

*

Canadians' emissions are 3x the global average. Albertans' emissions are more than 10x the global average. If people around the world copy us, global emissions would skyrocket. Canada ranks 10th in total emissions overall. Nowhere near ninth in population.

If Canada exempts itself from meeting climate targets, why wouldn't other countries do the same?

*

Using Canada's nominal (under-) estimates, 147 countries emit less climate pollution than AB's oilsands industry. 169 countries emit less climate pollution than AB. 183 countries emit less climate pollution than Canada.

If Canada is "too small to matter," what message does that send to the 187 nations with smaller carbon footprints than ours?"

Hi Geoffrey,

Thanks for the comments and additional quotes and data points. Couldn't agree more.

Cheers,

James

Great article. The truly sad part of Mr Mackay's nonsensical spewing to his oil industry base, is that he fails to grasp the fabulous potential that a country like Canada has to develop new energy options that can then be sold to the world. The one thing Conservatives once stood for was economic intelligence, and an eye to make the economy grow. That has been lost, unfortunately.