Thank you for helping us meet our fundraising goal!

Tech companies are taking unprecedented steps to deal with the flood of coronavirus-related misinformation sweeping across social media, but potentially dangerous myths and conspiracy theories are still making their way onto most major platforms. There’s a simple step that platforms could take to make it easier for users to flag this content for removal — but three months into the outbreak, they’re still not doing it.

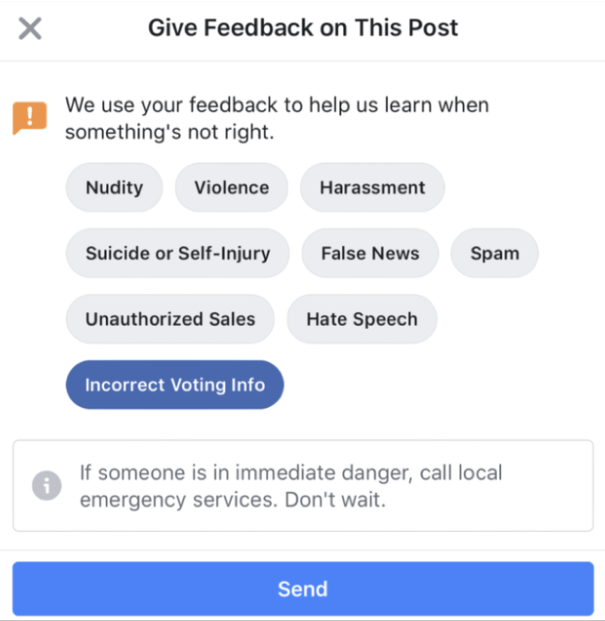

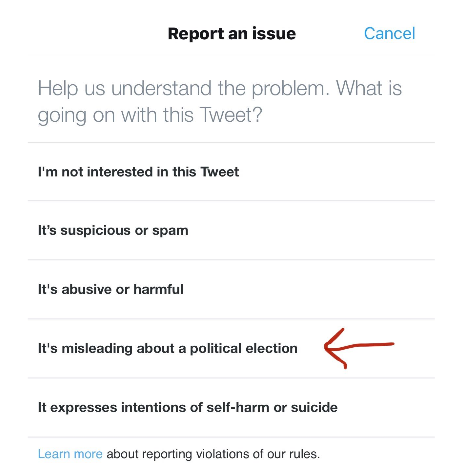

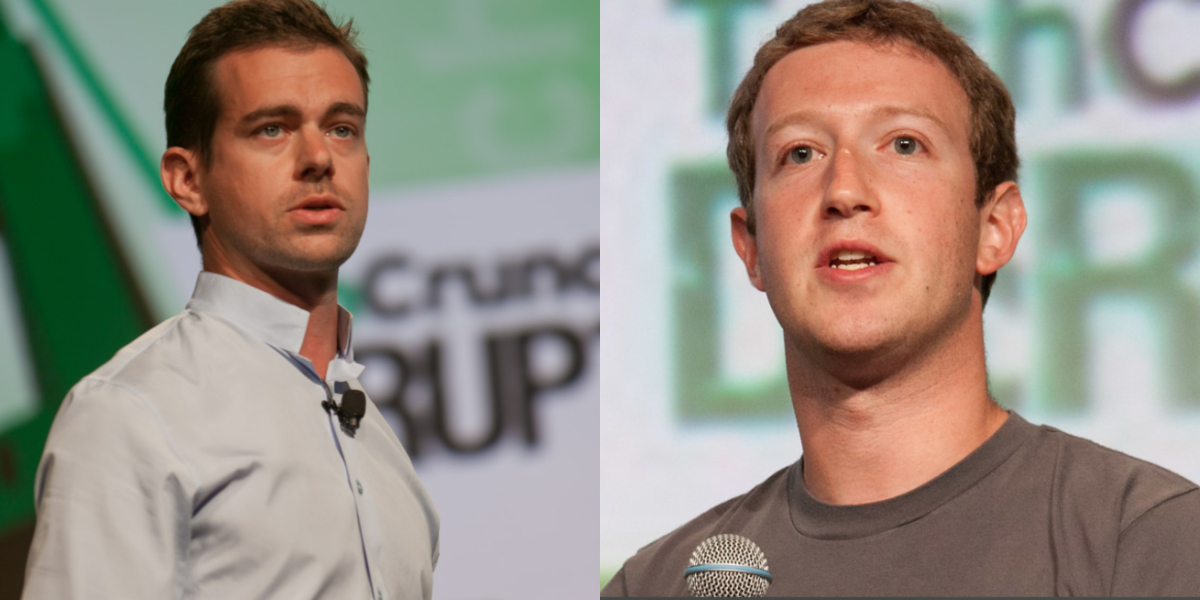

Facebook, the world’s largest social network, doesn’t have an option for its 2.4 billion users to report harmful content related to COVID-19. Nor does Twitter, which is used as a news source by an estimated 71 per cent of people on the platform.

Both have special reporting options for election-related misinformation, but when asked why they hadn’t done the same thing for dangerous misinformation about COVID-19, neither company gave an explanation to National Observer.

In the face of our current misinformation crisis, experts say broad approaches that incorporate proactive measures as well as responsive and corrective actions are necessary to even make a dent. Adding an option to flag potentially harmful coronavirus content may not solve the problem on its own, but at a time when people are exploiting a crisis for cash and pushing misinformation that could carry deadly consequences, even the smallest steps to remove harmful medical advice and false claims about cures could save lives. And social media users want to help. With the addition of a coronavirus-specific reporting option, platforms could leverage the collective knowledge and observations of millions

On Twitter, coronavirus-related tweets are posted every 45 milliseconds on average, according to the company. An estimated 15 million tweets about the virus were sent within the first four weeks of the outbreak, and the conversation has rapidly gained momentum since then.

On March 11 — the same day the World Health Organization designated the coronavirus outbreak as a pandemic — there were more than 19 million mentions of coronavirus across social media and news media platforms, outpacing every other major world event or issue by huge margins, according to the social media analytics firm Sprinklr. For comparison, climate change had fewer than 200,000 mentions during the same 24-hour period, and mentions of U.S. President Donald Trump numbered around 4 million.

What are the platforms doing to address coronavirus misinformation?

Since the start of the coronavirus outbreak in December, Facebook and Twitter — along with other major social media platforms such as YouTube and Pinterest — have taken much more proactive approaches to addressing misinformation than we’ve seen them take for any other issue, including foreign election interference.

The actions they’re taking fall into three main categories: promoting accurate information from reputable sources, removing harmful information, and stopping misinformation from making it online in the first place.

Facebook, for example, is “removing false claims and conspiracy theories that have been flagged by leading global health organizations,” a company spokesperson told National Observer. They’re also blocking exploitative ads that promise a cure for the virus, and they’ve placed a temporary ban on ads for medical face masks.

In addition to removing harmful content, Facebook has also modified its algorithm to promote authoritative information from trusted sources such as the World Health Organization (WHO). In Canada, Facebook users will see a pop-up in their News Feed directing them to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)‘s website, and anyone who searches for coronavirus will see the same.

Twitter is taking similar steps. Users who search for common coronavirus-related hashtags will see posts from national and international health organizations pinned to the top of their search results, and Twitter says they’ve been “consistently monitoring the conversation […] to make sure keywords — including common misspellings — also generate the search prompt.” Opportunistic targeting of ads is prohibited, as are promoted posts that advertise medical face masks.

“In addition, we’re halting any auto-suggest results that are likely to direct individuals to non-credible content on Twitter,” the company said. “[O]ur goal is to elevate and amplify authoritative health information as far as possible.”

Both Twitter and Facebook are doing a commendable job of making accurate information about coronavirus more accessible. The platforms are also allowing agencies such as the WHO to disseminate public health information through promoted posts (at no cost) in order to maximize the reach of awareness campaigns, emergency alerts and updates. They’re also working with health organizations and nonprofits, including fact-checking agencies, to share potentially valuable data and debunk common myths and misconceptions.

But when it comes to identifying and removing potentially dangerous misinformation, there’s a lot of work to be done, and simply providing accurate information is necessary but very often not sufficient for countering the effects of the mis- and disinformation that people see on social media, especially regarding health-related issues such as vaccines. The sheer volume of false, misleading, and conspiratorial content on social media can overwhelm users and make it difficult to discern authoritative sources from the rest of the crowd.

Why isn’t there a way to flag misinformation about coronavirus?

In the face of widespread criticism over social media’s role in amplifying disinformation during the 2016 election, Twitter and Facebook started rolling out new policies and features aimed at addressing harmful election-related content.

In Oct. 2018, Facebook introduced a special reporting option “so that people can let us know if they see voting information that may be incorrect” and/or may encourage voter suppression. Before then, users could still report election-related misinformation, but there was no way to automatically flag it as such.

Twitter rolled out a similar feature in 2019 that allows users to flag and report tweets that contain false or misleading information about elections, just like they can do for tweets that include harassment, abuse, spam, or threats of self-harm. The feature was first introduced in India last April during that country’s elections, and in the European Union ahead of its May 2019 elections, then finally in the U.S. in January 2020. Twitter’s terms of service already prohibited tweets that may mislead voters about an election, as well as tweets that intend to suppress turnout or intimidate someone from voting.

"This reporting flow has been an important aspect of our efforts since early 2019 to protect the health of the conversation for elections around the globe,” Carlos Monje Jr., Twitter’s director of public policy and philanthropy, said when the tool was introduced in the U.S.

Yet Twitter hasn’t offered a special option for reporting coronavirus misinformation to “protect the health of the conversation” amid a global pandemic, nor has Facebook.

While a reporting option wouldn’t suddenly fix the problem, it would give users an easy way to flag potentially dangerous coronavirus misinformation so it doesn’t get lost in the estimated 1 million user violation reports it receives every day.

Asked how Facebook would respond to a user who questioned why they had created a special reporting option for election-related misinformation, but not coronavirus misinformation, a company spokesperson told National Observer:

“Everyone has a role to play in reporting misinformation and we encourage people to report content they think may be misleading. Right now we encourage people to use the reporting features that are currently available and we’re working as quickly as possible to offer helpful resources across our platforms.”

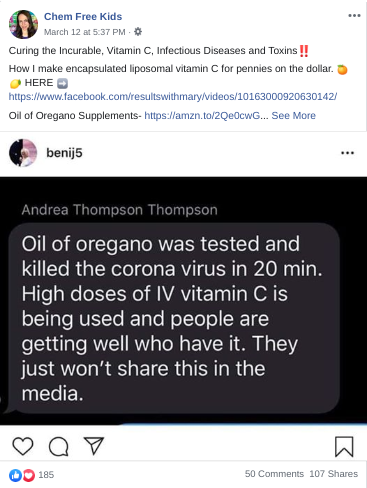

But the reporting features that are currently available don’t always work. I informally tested this out by reporting several misleading and false Facebook posts about coronavirus from an anti-vaccine page. Several days after I reported them, the posts — including one that suggests vitamin C and supplements are a cure — are still up.

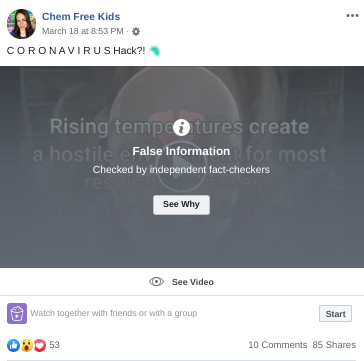

Another post, which suggests inhaling steamed water to create a "hostile environment" for coronavirus, got flagged as false by fact-checkers, but was not removed from the website.

Facebook has long faced criticism for inconsistently enforcing its own rules. As Tech Crunch put it last year: “Inconsistency of policy enforcement is Facebook’s DNA.”

The story is similar for Twitter. When asked why the company hasn’t created a tool for reporting coronavirus misinformation similar to the one they made for election-related misinformation, a spokesperson referred National Observer to a recent blog post on the platform, outlining what the company is doing to reduce coronavirus-related misinformation.

“At present, we’re not seeing significant coordinated platform manipulation efforts around these issues,” Twitter reported.

The platform has not reported numbers or analytics that could help quantify the scope of the coronavirus misinformation problem, nor has it publicly shared data reflecting the impact of its own response. National Observer asked if Twitter could provide any of these statistics, but the spokesperson did not respond to the question.

Twitter said it would continue working to strengthen its own “proactive abilities” to protect users from malicious behaviors, adding: “As always, we also welcome constructive and open information sharing from governments and academics to further our work in these areas — we’re in this together.”

National Observer reached out to the company with follow-up questions, but had not received a response as of press time.

Social media researcher Geoff Golberg, founder of the data analytics company Social Forensics, said he’s not surprised by the response from Twitter. When developing new rules and policies, social media companies often prioritize things that sound and look good, but aren’t necessarily the most impactful in practice, he said.

“Here’s the reality: we need effective solutions, not simply bells and whistles,” Golberg told National Observer.

For the same reason, he cautioned that although adding a specific reporting option for coronavirus misinformation would make it easier for users to flag harmful content, it wouldn’t guarantee that Twitter actually acts on those reports. “[W]hat really matters is what happens after that reporting option [is] selected,” he added.

There’s good reason to be concerned about that, too. Twitter is notoriously inconsistent in its enforcement of its own rules — a long-standing problem that human rights group Amnesty International said “creates a level of mistrust and lack of confidence in the company’s reporting process.”

Take, for instance, a series of tweets sent by Trump last week that suggested taking a drug combination that has not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and which doctors in China and the U.S. are warning could be deadly or could lead to a deadly shortage if people hoard the medication.

A short time after Trump posted the tweets, Nigerian health officials reported two cases of poisoning from the drug Trump recommended, and on Monday, one person in Arizona reportedly died and another was hospitalized after trying to fend off the virus by ingesting chloroquine phosphate — an additive often used to clean the inside of aquariums. The two individuals are believed to have confused the chemicals with chloroquine, the drug Trump promoted on Twitter.

Trump’s tweets have not been removed, even though they contradict Twitter’s latest policies around coronavirus misinformation. They also do not carry the warning label that Twitter said it would apply when world leaders post potentially harmful or dangerous messages. The warning label was touted as a mechanism to flag harmful content in cases where banning an account is not a viable option because it may go against the public interest.

Ultimately, Golberg said, “Twitter’s inability/unwillingness to enforce their own rules results in an information environment where nothing can be trusted” — at a time when trust in authoritative information could, quite literally, mean the difference between life and death.

If social media companies don’t want to add new features to make it easier to report and remove coronavirus misinformation, “enforcing their current rules — and in a consistent, non-selective fashion — would be a good place to start,” Golberg added.

Comments

A new twist on "Death by Algorithm".

Yes I agree with the statement.

In addition to the extensive content about Twitter and Facebook there are problems with Google and You Tube. A percentage of the posts on You Tube are misleading and contain in accurate information. In some cases I've received emails from friends the contain links to You Tube that are videos about the Covid-19 virus that are misleading. My advise is be very careful what you believe in all Social Media platforms. Some of it if followed may kill you.

What? Delete POTUS tweets?

Folks, think about it. We've been told it's transmissible only in "cough droplets." But pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic people are contagious.

Check out this study synopsis by the two lead researchers:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/20/eradicated-corona…

14 days to prevent any new cases

I live in a large city, but would suggest that if rural areas were tested first, those areas without access to hospitals would be cleared ... there could be progressive testing-by-area, and if people in cities maintain Toronto's current mode, with all workers in essential services and their households tested.

But one has to wonder why, when we had the first case 2 months ago, we are still short of test swabs, and still no lab capacity to produce speedy results. How long would it take if the political will were there?

In the midst of considerable misinformation and confusion re.

COVID-19, some facts get shelved incorrectly. Vitamin C can be beneficial,

and based on positive experiences two trials are listed on the international

site for trials registration. These trials are for people in very dire

straits clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03680274 and

clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT04264533

Apparently some hospitals and practitioners are administering vitamin C a bit

earlier

https://nypost.com/2020/03/24/new-york-hospitals-treating-coronavirus-p…

I am not a physician, and am not dispensing treatment advice, but vitamin C

is among the very lowest risk vitamins. Linus Pauling and many modern

physicians have a point, that taking ascorbate (the chemical name for vitamin

C) "to bowel tolerance" may ameliorate effects of infection, assist immune

response, and speed healing.