Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Canada's managed forests, and the wood taken out of them each year, have become one of our country's largest -- and yet most confusing -- sources of climate pollution. This forest carbon explainer tells the story of:

- The climate crisis unfolding in Canada's managed forest lands, as they flip from much-needed carbon absorbers into super-emitters

- How unnatural surges in insect outbreaks and wildfires are fueling the crisis

- The troubling data showing that logging is now extracting more carbon than grows back, pushing our forests over the edge

- And finally, the government's scramble to push the crisis, and any responsibility for it, off the books

This story is told in three parts below, each with increasing detail. It starts with an "Overview" section that covers the big picture. Then, for readers wanting more in-depth reporting and detailed charts, a "Digging Deeper" section follows. Finally, at the end, an extensive Q & A with links provides an even deeper dive into some key data.

Overview

A major climate crisis is unfolding in Canada's managed forest lands, as they tip from carbon absorbers to super-emitters. Put simply, our forests are now dying and being cut down faster than they are growing back. That's according to data in Canada's latest official National Inventory Report (NIR).

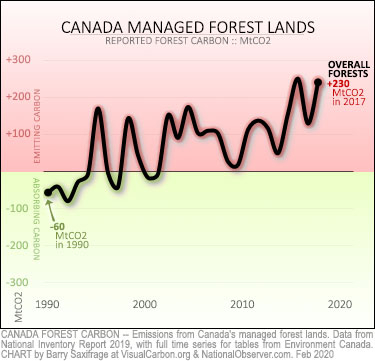

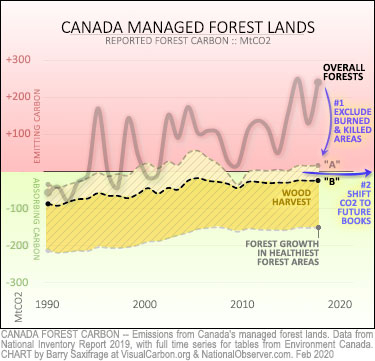

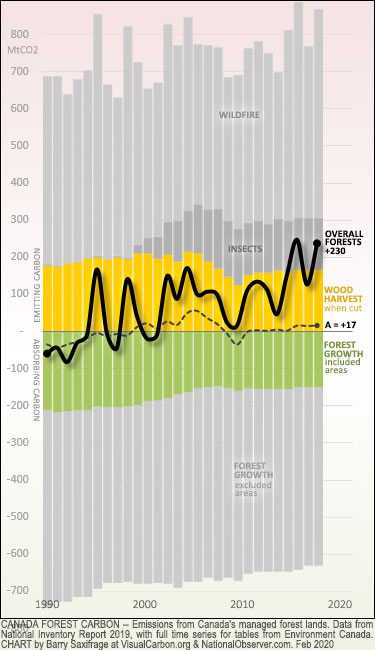

My first chart shows the overall trend. The green area means the forests are gaining carbon; the red area means they are emitting it. And the bold black line shows the net carbon balance of our managed forests.

As you can see, these forests reliably gained carbon in the past. They were critical CO2-absorbing sinks.

But not anymore.

Now they've flipped to emitting CO2. Lots of it. In 2017, they lost 230 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2).

Driving this trend is an un-natural surge in native insect outbreaks and wildfires. Humans are turbocharging both. Our relentlessly high levels of fossil fuel burning are rapidly altering the climate in favour of more insects and infernos. In addition, decades of poor land use practices have produced unfit, vulnerable, monoculture forests.

Logging more than grows back

As our managed forests have weakened under the strain, they are no longer replacing the amount of carbon that logging is taking out of them.

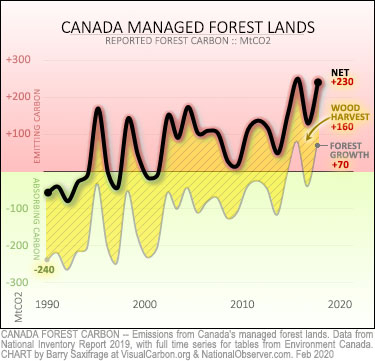

My second chart breaks this down. Canada reports forest carbon in two parts: forest growth (grey line) and harvested wood (yellow area).

Harvested wood volumes have averaged 185 MtCO2 worth per year, since 1990. In recent years, it's been around 160 MtCO2 worth.

All that extracted forest carbon used to be replaced each year as new growth pulled even more CO2 out of the air. But our faltering forests can't keep up anymore. Now logging is pushing our forests over the edge from absorbers to emitters. And all the excess logged carbon is accumulating in our atmosphere -- just like CO2 from fossil gas, coal and oil.

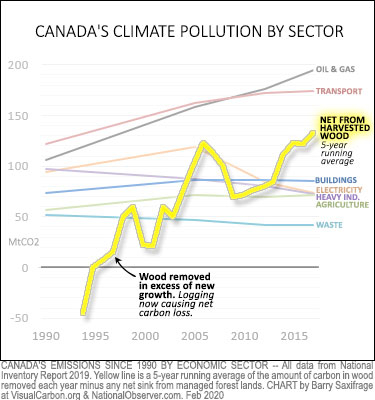

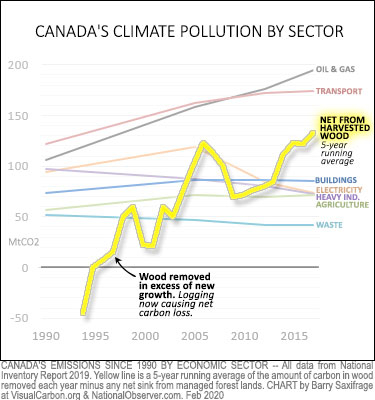

To illustrate the scale of this new climate threat, I've charted it next to Canada's other sectors.

The bold yellow line shows the amount of carbon in harvested wood that exceeds what our managed forests are absorbing.

As you can see, excess logging carbon now exceeds emissions from entire sectors like buildings, electricity generation or heavy industry.

That doesn't look like "carbon neutral" wood to me. Just the opposite. It looks like a gigantic new source of climate pollution that we will need to reign in, pronto. The burning question is how?

One obvious policy option is to treat excess carbon from forestry like we treat excess carbon from fossil fuels -- putting it under the same climate target and levying the same carbon pricing on it. That would at least provide some incentives and tools to push this new emissions source back down again to safe levels. After all, the climate reacts the same to both.

Instead, the government has been working to push the carbon bomb exploding in our managed forest off the books. Well … off the current books, anyway. And to do that they had to weaken their carbon accounting rules in three significant ways.

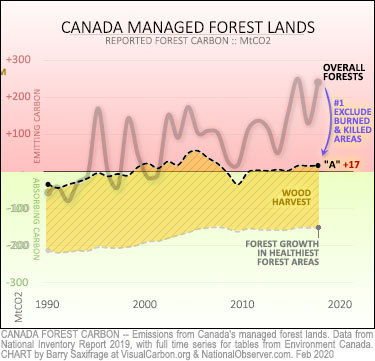

Rule change #1 -- ignore most of it

The first change was to stop reporting on any forest areas that have been heavily impacted by fires, insects or extreme weather. This change pushed a quarter of Canada's managed forest lands -- and most forest emissions -- off the books.

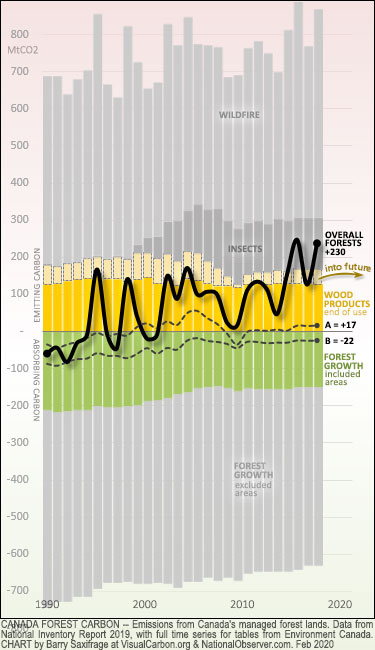

Canada's emissions inventory used to cover all managed forests. Now it only reports the healthiest forest areas called the "reported areas". The carbon balance for this subset is shown by line "A" on the chart.

In 2017, Canada's managed forests lost 230 MtCO2. That's what Canada used to report on its books. But now it reports only 17 MtCO2. Even so, that's still more than the entire province of Nova Scotia emits from all sources. Pulling out more forest carbon than grows back makes it hard to claim that all that extracted wood is "carbon neutral." So, a second rule change was brought in that pushed even more forest carbon off the books.

Rule change #2 -- push gigatonnes into the future

Historically, Canada reported the carbon in harvested wood in the year the trees were cut. This is the default method approved by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) rules.

Two years ago, the government switched to reporting harvested wood carbon when the wood is no longer useful to humans. This change pushed a quarter of harvested wood CO2 off the current books -- and deposited it on the future books. The light-yellow area on the chart shows how much is now being moved to the future.

This second change lowered the official forest carbon reporting down to the line labelled "B" on the chart. With these two changes, Canada has flipped from reporting its managed forests as a surging super-emitting crisis, to reporting them as calm, stable, ongoing carbon sinks. Nothing to see here. Move along.

Unfortunately for Canadians in the future, all that harvested wood CO2 we are no longer claiming must be reported eventually. So, the government quietly slipped it onto the future books. It's there, waiting for Canadians to deal with later. And it's an eye-watering amount. Already, more than two billion tonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) has been shifted over. Apparently, filling our kids' atmosphere with CO2 wasn't enough. Now we're loading up their "net-zero" carbon books with heaps of it as well.

Rule change #3 -- weaken the target

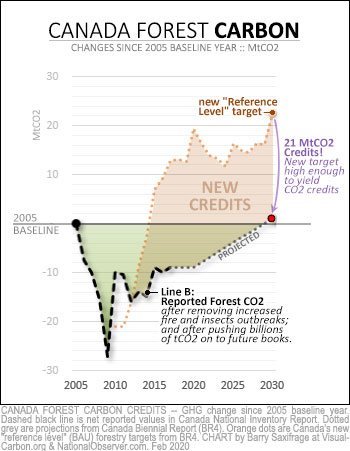

Ottawa has been wanting to use a big whack of forest carbon "offsets" to meet Canada's 2030 climate target. But our forests are collapsing so fast that even the two huge rule changes discussed above weren't enough to save any. So, the government made a third rule change to weaken the target used to claim offsets.

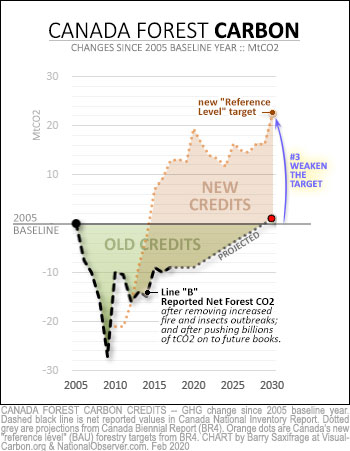

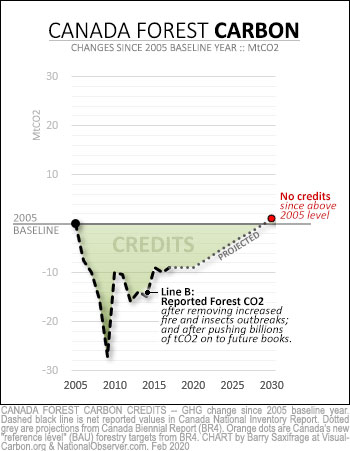

Historically, Canada has used the same target for all its land use sectors, which includes managed forests and the wood logged out of them. This target is zero per cent below their 2005 baseline level. My next chart shows how this applied to managed forestry.

The bold grey line is the managed forests' 2005 baseline. Anything below that would be claimed as "carbon credits" towards meeting our climate targets (green area).

However, as the chart also shows, emissions are projected to rise above that baseline by 2030 (red dot). That means no offsets.

So, the government decided to create a new, weaker, type of climate target just for managed forests. It's called a "reference level" target and is shown by the orange dotted line on the chart. This is their guestimate for business-as-usual. Now, anything below this guestimate (orange area) will be used to "offset" emissions elsewhere.

As you can see, this third change weakened the target so much that it turned zero credits into more than twenty million tonnes of credits.

Okay, okay … I can guess what you're thinking. The government can't just make up some new target that keeps getting weaker and weaker over time. And they can't possibly claim that rising emissions in one sector can somehow "offset" rising emissions in another sector. Even if they could, Canada isn't that pathetic … right?

In summary, the government's own data shows that Canada's managed forests, and the wood taken out of them each year, have become one of our country's largest climate pollution sources. Logging now extracts vastly more carbon than is growing back -- tipping our forests from weak CO2 sinks into massive CO2 emitters. Rather than taking responsibility for our actions that are driving this new threat, the government is trying to push it all off the books through "creative" accounting, generational burden shifting and fake "offsets" schemes.

The climate science has been clear for decades that the only path we have to avoid a full-blown climate crisis is to quickly eliminate all our CO2 sources. And, now, as our faltering forests are warning us, we are rapidly running out of time.

Digging Deeper

For those wanting more of the nitty gritty details, here's a deeper dive into Canada's forest carbon story.

Forests flip, emissions soar

As we saw in the overview, Canada's forests have flipped from carbon absorbers to super emitters.

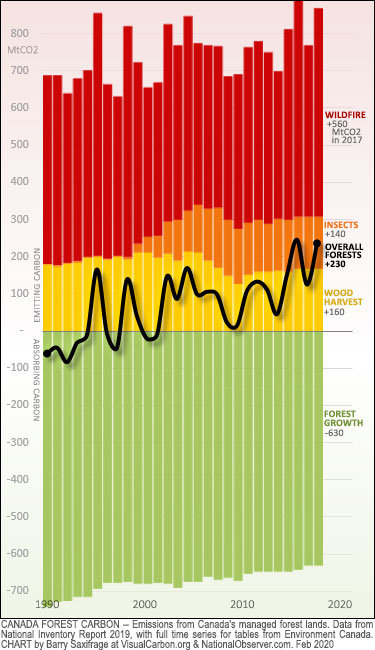

To better illustrate what's going on, I've charted the data in more detail on the right. This covers all our managed forest lands.

The major sources of CO2 are wildfires (red), insect outbreaks (orange) and harvested wood (yellow). Counteracting these, in green, is the CO2 being absorbed by our forests as they grow.

The net emissions from all these forces combined is shown by the bold black line.

As you can see, back in the early 1990s, our managed forests reliably gained around 50 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) each year.

Now carbon losses from fires, pests and logging greatly exceed what our forests are gaining from new growth. In the last five years, net forest carbon losses are averaging around 160 MtCO2 per year. The worst years now exceed 200 MtCO2.

As the chart also shows, this shift has come partly from increased emissions and partly from decreased growth. The orange and red bars show the rising emissions from native insect outbreaks and wildfires. The shrinking green bars show the steady decline in forest growth. It's a one-two punch.

How should Canada respond?

Clearly, such a big new climate threat needs equally big new policies to contain it. But which of the many possible options should Canada adopt? As we saw in the overview above, the amount of wood harvested by logging now exceeds what the forests can re-grow each year.

So, the climate-safest option would be to limit the amount of carbon we extract from our forests to the amount that grows back each year. That would prevent logging from becoming a gigantic new source of CO2 accumulating in our atmosphere.

Essentially, it would require that big yellow line in the chart on the right to return to zero or below.

A second option would be to treat excess forest carbon the same as other excess carbon sources like fossil gas, coal and oil. That would mean putting it under the same climate targets and carbon pricing.

For example, in Canada last year burning coal and burning forest carbon for energy each emitted around 56 MtCO2. All the CO2 from coal is included under our 30 per cent reduction climate target; and it is subject to our national carbon pricing. But none of the CO2 from burning forest carbon is. Maybe that made sense when it got re-absorbed each year. But now it's accumulating in our atmosphere, just like coal CO2. If we are going to extract extra forest carbon, we should at least treat it like other excess emissions sources.

But as we also learned in the overview, the Canadian government isn't planning new climate policies to lower this new source of emissions. Instead, it's trying use creative accounting to shift all responsibility off the current books. They've needed three big changes, so far, to do it:

- Exclude most forest emissions from the books

- Shift billions of tonnes of logging carbon on to future books

- Weaken forestry's climate target

Let's take a more detailed look at each of these changes.

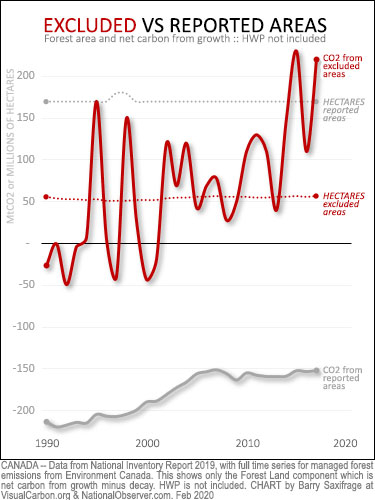

Change #1: Excluding most forest emissions

As emissions have risen from insect-outbreaks and wildfires, the government decided to remove them from the books.

The result can be seen below. Emissions that are now excluded are shown in grey. Yep, that's most of them. Specifically, the new rule excludes any forest areas in which more than twenty per cent of the forest has been recently impacted by events such as wildfires, insects and hurricanes. That excludes about a quarter of our managed forests.

Emissions and absorption from these excluded areas are still tracked, but they aren't reported on the books. When an area recovers to a certain level, the area gets moved back into the reporting group. At that point its future emissions and absorption get reported in Canada's official inventory.

The areas that have not been excluded are referred to as the "reported areas." Emissions from these reported areas are shown by the green and yellow bars on the right.

The green bars show net growth in the reported areas. In recent years these have been absorbing roughly 155 MtCO2 per year.

The yellow bars show the wood getting taken out by logging. That's been averaging around 165 MtCO2 per year -- which is 10 MtCO2 more than is growing back even in this selected healthiest subset of the forest.

The net carbon balance for these "reported areas" is shown by dashed black line labelled "A".

Under the old rule Canada would have reported that its managed forests lost 230 MtCO2 in 2017. Now, by excluding a quarter of that forest land base, Canada is reporting just 17 MtCO2 of that.

While that’s a lot lower, it still shows logging extracting more carbon than is growing back. That makes it harder to claim carbon neutral wood, not to mention earning "forest carbon credits" on top of that. So, more changes were needed.

The stated reason for excluding wildfires and insect outbreaks is that they are "natural" rather than "anthropogenic" disturbances. It's an odd choice of terms considering that humans are driving the rise of both.

Wildfires and insects aren't new to Canada's forest. As the charts above show, our forests used to be able to handle natural levels of wildfires and insects -- and even our logging too -- and still be net absorbers of CO2.

What's changed is that wildfires and native insects have surged to un-natural levels. And human actions are fueling both.

Climate science has long been shouting warnings that continued high levels of fossil fuel burning will lead to rising wildfires and insect-kills in Canada's forests.

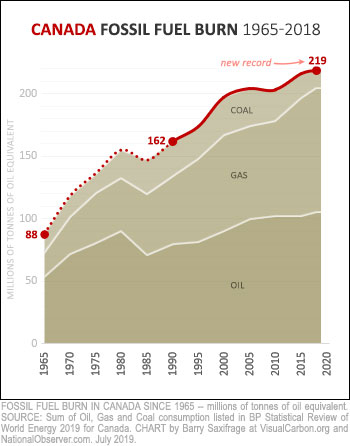

But, instead of reducing our fossil fuel burning as required, and repeatedly promised, Canada keeps burning more. In fact, last year we burned an all-time record amount.

In contrast, the European Union and the United States both hit peak fossil fuel use more than a decade ago. Heck the U.K. did it 40 years ago. So, clearly it is possible for modern wealthy societies to turn down the burn.

In addition to cooking our forests, we've also been actively managing them in ways that are contributing to the surge in wildfires and insects damage -- like fire suppression, accelerated re-growth strategies, monoculture forestry and "Molotov clearcuts" to name a few.

So, it seems a stretch to me to pretend we don't have any responsibility for the emissions that we are actively fueling.

Change #2: Shifting gigatonnes of carbon into the future

The government's second big change was how it reports the carbon in harvested wood products (HWP). HWP is all the wood physically removed from forests by logging and firewood gathering. And that's a lot -- averaging 183 MtCO2 worth per year since 1990.

Historically Canada reported all the carbon in harvested wood in the year it was cut. That's the yellow bars discussed earlier in the charts above. This is the default method approved by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) rules. This method has clear benefits, including:

- simple to calculate,

- transparent to the public,

- keeps responsibility close to when the logging decisions and profits are made, and

- doesn't push additional burdens onto future generations.

A couple years ago, however, the government created a new method. It delays reporting the carbon until the year the wood is no longer useful to humans.

To calculate when each piece of harvested wood is no longer useful, the government built an HWP computer model. This attempts to simulate the fate of all harvested wood; which products get made from it; and how long each is used. It's complicated, full of assumptions and totally opaque to the public.

My revised chart on the right shows the difference between the two methods. Dark yellow bars show what now gets reported under the new method. The lighter-yellow bars above them, show how much more was actually logged each year.

As you can see, this new method reduces reported HWP emissions in every year so far. On average, 35 MtCO2 each year has been removed from what was previously reported.

The short-term pay off is that reported forest carbon drops down to line "B" on the chart.

As a result, Canada now reports that its managed forests -- even after all the harvested wood is removed -- are steady, reliable, on-going carbon sinks. Carbon bombs are re-classified as carbon saviors.

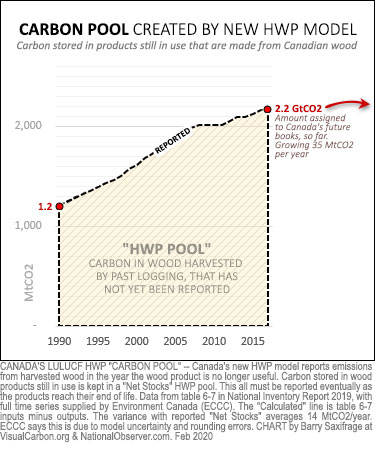

Unfortunately for Canadians in the future, all the HWP carbon we are no longer claiming must be reported eventually. Ottawa's new HWP computer model resolves this by quietly assigning it to the books in future years. It's already there waiting for Canadians to deal with later. And it's a lot – more than two billion tonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) and still growing.

My next chart lets you see just how much we are "gifting" to Canadians in the future, and where it is coming from.

Under the government's new HWP computer model, each year's harvested wood gets added to a big "HWP carbon pool". That's the light yellow area on the chart. Then whenever the model thinks a piece of wood in that pool has reached its end of usefulness, that carbon is removed and reported as an HWP emission in that year.

In every year since 1990, more carbon has gone into the HWP pool from logging than has come out in emissions. So, the pool keeps getting larger.

In 1990, the pool held over one billion tonnes. That was the amount estimated to be stored in wood harvested before 1990 but not yet at the end of its useful life. Since 1990, another billion tonnes have been added.

On average, 35 MtCO2 more is being added to this pool every year. For scale, that's like choosing to take all of Nova Scotia's and New Brunswick's emissions off our books and assigning them to the future books, instead. Hey, why not? Just don't tell the kids.

Change #3: Weakening the target

Amazingly, the government's first two big accounting changes -- pushing most emissions off the books and then shifting gigatonnes more onto future books -- still aren't enough to serve up "forest carbon credits" for Canada's 2030 climate target.

As most climate observers know, Canada is one of the world's "Dirty Dozen" climate polluters -- both as a nation and per person. Under the global Paris Agreement, Canada promised to finally do something about that by cutting our climate pollution 30 per cent below our 2005 baseline level by 2030.

That well-known target covers nearly all our economy. But Canada excluded one sector from it -- our Land Use and Forestry sector (LULUCF). They put this sector, which includes managed forests and the wood extracted from them, under a weaker target of zero per cent reduction below 2005 levels.

The government stipulated that any reduction in LULUCF emissions below 2005 levels would be claimed as a "carbon credit" that will be used to "offset" emissions elsewhere.

My chart on the right shows how this zero-ambition target applies to managed forests.

The bold horizontal grey line is the 2005 baseline for managed forests.

Anything below that baseline would be used as a "carbon credit" (green shading).

Unfortunately, as you can see, even with both accounting changes discussed above, net forest carbon is still projected to end up above the baseline in 2030 (red dot). That means no credits.

Now what?

The government's third change was to create a new kind of climate target -- just for managed forests and the wood logged out of them.

They call it a "reference level" target. Essentially, our government guestimates "business-as-usual" (BAU) scenarios for Canada's managed forests. There is one BAU guestimate for 2010 to 2020, and a second for 2020 to 2030. These are both shown in the dotted orange line on the chart.

The government says it will now use this BAU line to determine how many "carbon credits" it will claim. Anything below it (orange shading) will be used to "offset" emissions elsewhere.

Voilà. Weakening the target created more than twenty million tonnes of "forest carbon credits" on the books to use in 2030. These will "offset" emissions from other sectors.

Ottawa has finally found the new carbon math it's been searching for, in which rising emissions offset rising emissions. One plus one equals zero.

Sorry, kids

As we've seen in this walk through the thorny thicket of Canada's forest carbon, it takes a lot of heavy lifting to haul "carbon credits" out of forests that are hemorrhaging CO2.

First, our government had to lift hundreds of millions of tonnes of CO2 that we helped create, off the books and stuff them under the couch cushions. Then they needed to go back and lift billions of tonnes more and haul them over to the kids' side of the ledger. And finally, they need to lift that pesky target and drag it tens of millions of tonnes higher, so we can pretend that burning dangerous-to-our-kids amounts of fossil fuels isn't … well … dangerous to our kids.

Our youth appear increasingly unimpressed by our convoluted efforts to avoid doing the actual heavy lifting required to pass along a safe and sane climate to them -- reducing our emissions rapidly to zero.

They understand the incompatibility between the increasingly dire climate science and our foot-dragging shenanigans -- like these fake "offsets" from collapsing forests. So, it's no wonder they are growing anxious, angry and marching in the streets worldwide in protest. Swedish climate striker Greta Thunberg has recently resorted to pleading with adults "to act as if you loved your children above all else."

Maybe its time we listen to them and try a new path forward in Canada -- let's create a plan that meets our climate commitments and actually do it.

Canada Forest Carbon Q & A

Canada's forest carbon reporting is growing increasingly complex, confusing and constantly changing. I spent weeks trying to unravel the details and collect the data. For those interested in even more of the details about what's going on, here are answers to some commonly asked questions that didn't get fully covered above.

Q: Where can I find the data and additional information?

A: Here are links to the four main sources I used in this article:

- NIR -- Canada's National Inventory Report

- CRF -- the companion Common Reporting Format spreadsheets

- BR4 -- Canada's Fourth Biennial Report to the United Nation's

- Additional data from ECCC -- Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) provided me with the complete time-series for three important forest carbon data tables: NIR Tables 6-5, 6-7 and BR4 Table A2.46. You can download these here.

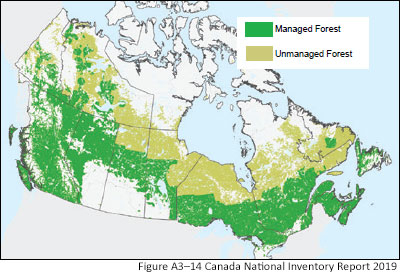

Q: How much of Canada's forest area is counted as "managed" forest?

A: Roughly 65%.

Canada only reports emissions from "managed forests." These are forests managed for timber; for non-timber resources (like parks); or subject to "intensive fire protection."

They total 226 million hectares and are roughly 65 per cent of Canada's total forest lands.

They are shown in dark green on this map from the NIR. Notably this includes nearly all the forests in BC and Alberta.

Most of Canada's unmanaged forest area is northern boreal forest.

Additional details: see NIR table 6-4 plus the text in section 6.3. Also see CRF Table 4.1.

Q: How much managed forest is now excluded under new accounting rules?

A: One quarter of its hectares; most of its emissions.

Historically, the "Forest Land" line in Canada's NIR included emissions from all its managed forest lands. Recently that was changed to exclude areas heavily impacted by certain disturbances like fire, pests and hurricanes.

The number of hectares excluded each year by the new rule is shown by the dotted red line on my chart. This has held fairly steady at around 55 million hectares -- one quarter of Canada's managed forest lands.

Note that this is a constantly shifting pool, with new areas being added while recovered areas get removed.

What hasn't held steady are the emissions from these excluded areas. They are shown by the solid red line. As we will see in more detail below, surging levels of insect kills and wildfires are driving this rising trend.

The grey lines on this chart show the values for the remaining areas. These are known now as the "reported areas." As you can see, the net growth (carbon uptake) in even these healthiest areas is also faltering.

Also, note that the emissions values shown on this chart do not include the carbon removed in harvested wood. This chart only shows the net carbon balance from growth minus decay in each group. This is the value reported in the "Forest Land" line of the NIR.

Additional details: see NIR table 6-5 (partial time series). For the full time-series to date, download the "additional data from ECCC" as described at the start of the Q&A section.

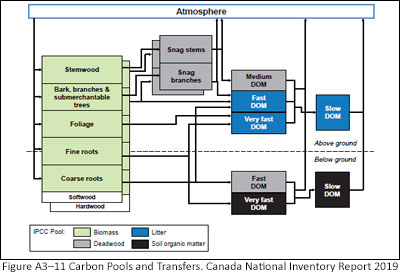

Q: How does Canada track forest carbon?

A: Canada uses two computer models to estimate carbon flows into, through and out of forests.

The basic concept is that a main Forest Carbon computer model simulates forest growth, decay and disturbances.

The schematic on the right gives a rough idea of the various "pools" and how carbon flows between them.

CO2 gets brought into the model via estimated forest growth each year. This CO2 gets converted to carbon in the model and is added to one of the living biomass "carbon pools" in the simulation (green boxes).

When the computer model calculates that living biomass dies, its carbon gets transferred through a series of dead organic matter (DOM) carbon pools -- such as snag branches, leaf litter and soil organic matter (grey and blue boxes). Eventually, rotting or burning releases most carbon back into the air as CO2. At that point, it gets transferred out of the forest model and is reported in Canada's NIR as an emission in that year.

Large scale events like fires, insect kills, storm blow downs and logging are all treated similarly in the model. Biomass that is killed has its carbon transferred from a living pool to one of the dead ones. Biomass that is burned, whether dead or alive, gets removed from that pool and leaves the model as an emission in that year.

In the past, all the carbon extracted by logging was reported immediately as "Harvested Wood" emissions in the NIR.

As discussed above, Ottawa has changed how they report extracted forest carbon. They now report it when each piece of logged wood reaches the end of its useful life to humans. To calculate this they created a second computer model called the HWP Model. Now, all carbon extracted by logging gets transferred from the Forest Carbon model to this new HWP model. It gets initially placed into a huge, and growing, "HWP Carbon Pool." Then the HWP computer model estimates what happens to each piece of wood and when it is no longer useful. In that year the model removes the carbon from the pool, converts it to CO2, and reports it in the NIR as a "Harvested Wood" emission.

Additional reading: these are complicated models that get data input from hundreds of sources and use dozens of tables that represent everything from how different tree species grow, to variables for how ecosystems respond to disturbances, to which wood products are made from each year's logging and how long they last. A semi-technical introduction to them can be found in NIR Annex A3.5 and BR4 Annex A2.

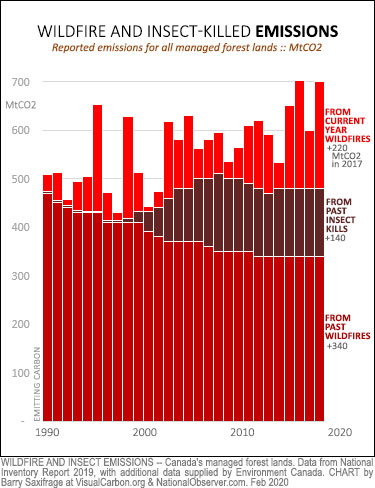

Q: Why don't reported emissions from wildfires and insects align with the reported severity each year?

A: Reported emissions come mostly from trees killed in past events.

Canada's Forest Carbon model reports emissions from fires and insects in the year the CO2 is actually released. My chart below shows the breakdown.

Wildfires instantly convert some forest carbon into CO2 by burning it. That's shown by the bright red bars on the top of the chart.

However, even more CO2 gets released in later years as the biomass that was killed in the fire -- but not fully burned -- finally rots and turns to CO2. That's shown by the dark red bars at the bottom.

Likewise, when insects kill a tree, very little carbon in that tree turns into CO2 that first year. Instead nearly all the CO2 caused by insect kills gets released in later years as the dead tree slowly decays (dark brown bars).

This chart also let's you see the recent dramatic surge in both insect kills and current year wildfires.

For example, current year wildfires are releasing 50 MtCO2 more per year over the last decade, than they did in the 1990s. And insect kills are averaging 135 MtCO2 more per year in the last decade. Climate science has long predicted that continued high levels of fossil fuel burning would bring these changes. The problem is expected to grow worse as climate shifts intensify.

Additional details: see NIR table 6-5 (partial time series without wildfire splits). For the full time-series to date, along with the splits between past and current wildfires, download the "additional data from ECCC" as described at the start of the Q&A section.

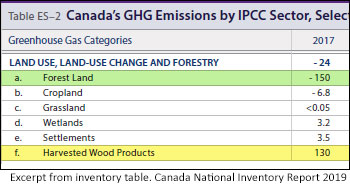

Q: Where in Canada's top-level climate pollution inventory is forest carbon listed, and how has it changed?

A: Canada continues to report managed forest carbon on two lines: "Forest Land" and "Harvested Wood Products". However, the meaning of each has changed significantly.

Canada splits its reporting on managed forest carbon into two top-level categories.

The first is "Forests Lands". This is the net balance between new growth vs new decay and forest burning.

The second is "Harvested Wood Products" (HWP). This is the carbon in all the biomass extracted from the forests by logging and firewood collection.

You need to add them together to get the forests' overall carbon balance.

Historically, "Forest Land" values covered all managed forest areas. Now "Forest Land" only covers a selected healthier subset of the forest known as the "reported areas." You can still find the number for all managed forests lands in the "Net Flux" line of NIR table 6-5.

Likewise, "HWP" values used to be all the wood harvested in a given year. Now it is a smeared collection of some wood that was logged in the current year and some wood harvested in all past years. The new HWP computer model chooses which wood to report each year based on its estimates of when each piece of wood is no longer useful. You can still find the value for how much wood was harvested each year by using the "Inputs to Carbon Stocks" line in NIR table 6-7. Be sure to covert the C to CO2 by multiplying by 44/12.

Additional details: NIR tables 6-5 and 6-7 (partial time series). For the full time-series you can also download the "additional data from ECCC" as described at the start of the Q&A section.

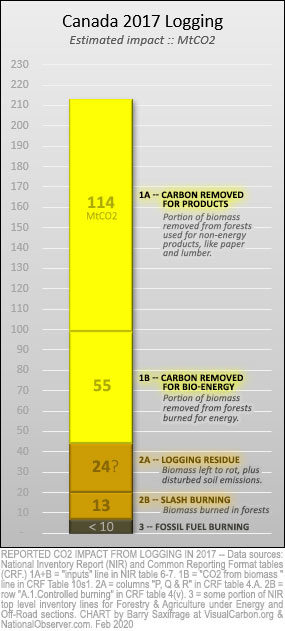

Q: How much CO2 is caused by a single year's logging?

A: Only some data is available. Below is an estimate of over 200 MtCO2 for 2017.

Logging creates emissions in three main ways:

1. Biomass removed from forest (harvested wood)

2. Biomass left behind (slash, residue and disturbed soils)

3. Fossil fuel burning.

Here’s what I could find about each of these, along with estimates for 2017.

1. Harvested wood -- 169 MtCO2

All biomass carbon removed from forests each year via logging and firewood collection is listed in NIR table 6-7. Use the "Inputs to Carbon Stocks" line, and covert the C to CO2. For example, the 2017 value is 46 MtC x 44/12 = 169 MtCO2 in wood removed from forests in 2017. This can be broken down into two main uses.

1A. Non-energy wood products -- 114 MtCO2

1B. Wood burned for energy -- 55 MtCO2

Much of the harvested biomass gets burned for energy each year. The amount gets listed in the "CO2 emissions from biomass" line in CRF table 10s1. As noted in the main article above, this source of energy CO2 is not included under Canada's 30 per cent below 2005 reduction target. Instead, it is counted under the managed forests target -- which is now changed to be a rising BAU guestimate. That means emissions from burning forest biomass for energy can rise while still generating "carbon credits." With such strong incentives to burn forest biomass I expect this to rise despite the grim reality that this wood is pushing forests from net carbon sinks into super-emitters.

2. Logging residue -- 37 MtCO2 ?

Only a portion the biomass killed by logging gets hauled away to be used. What remains behind as "logging residue" will become CO2 when it rots or is slash burned. In addition, soils exposed and disrupted by logging release a lot of CO2. These non-energy industrial emissions are known as "process emissions" and they get reported for other industries like cement (off-gassing) and oil & gas (fugitives). When asked, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) said these emissions are tracked in their Forest Carbon computer model. And they get reported as part of the NIR "Forest Land" value. But they are not reported separately. However, they said rough approximations could be made as follows:

2A. Logging residue left to rot, plus soils -- 24 MtCO2 ?

ECCC said columns “P”, “Q” and “R” in CRF table 4.A can be used to roughly estimate emissions from the killed biomass left to rot, plus from disturbed soils. My attempt to follow the math yielded ~24 MtCO2 for 2017. But I could be wrong, so if you need precision on this you should do the math yourself or ask ECCC for it. Also, they cautioned that the result will be a smeared mix of emissions from current and past years of logging and will include other things.

2B. Slash burning -- 13 MtCO2

Reported emissions from burning logging slash in the forest is listed in CRF table 4(V). Look for the "Controlled burning" line under "Forest Land Remaining Forest Land."

3. Fossil fuel burning -- probably less than 10 MtCO2

The forestry industry burns fossil fuels. In the NIR, most of forestry's fossil fuel emissions get lumped together with agriculture and reported under two categories: "Energy: Stationary Combustion: Agriculture & Forestry" and "Transport: Off-Road Agriculture & Forestry". Together these totalled 14 MtCO2 in 2017. However, the inventory doesn't break out forestry's share of this, so I've just listed a very rough "< 10 MtCO2" in my chart above.

TOTAL: more than 200 MtCO2 in 2017.

Additional details: Gathering the needed data for any year other than 2017 takes additional work. In particular, the CRF tables mentioned above only provide data for a single year. You need to download separate CRF tables from the United Nation's website for each year you are interested in.

Comments

I must admit that I did not read the complete article because there is lots of repetition. However, I scanned it and did not see any reference to the fact that a high proportion of the wood extracted from the forests is preserved in buildings and does not create CO2 emissions. The fraction that is converted into paper is not all transformed into CO2 either.

If managed properly, extracting trees to produce construction lumber stimulates new growth in the forest and reduces the damage and occurrence of forest fires.

Good points raised in Richard Asselin comments. The key words are "Managed Properly".

I think that they key word are actually "sequestered". How much of the logged carbon is released into the air, and how much is locked into wood products.

This is a reasonable way to measure and must be accurately counted in order to evaluate the constructions industry's current move to wood to replace concrete. Yes a tree farm is not a forest,: another issue.

whatever the reference level is, it looks to me like the government is trying to find a way to pay managers and first nations for the service of preserving forests and good forest management. Which wold be good, as long as the emmissions (not removed carbon) are honest.

Nearly all harvested wood ends up as CO2 or methane emitted into the air eventually. It all has to be reported under IPCC rules. The only question is whether the people reaping the benefits take the responsibility...or whether it gets pushed onto future generations to take the hit at the point that the wood is useless to them. I have my opinion on that. You can form your own now that you have the info.

Thanks for the comment Richard. Almost all the wood harvested becomes CO2 eventually, even the wood in buildings. The IPCC rules require that countries report this CO2. The only question is when it is reported. The default, as discussed in my article, is to report it in the year the wood was cut. That's called "instantly oxidized" accounting. It has lots of benefits for the public. That's what Canada used to use. Now Canada reports the CO2 when the wood reaches end of useful life. That might be more "technically accurate" but it is a choice that puts a huge burden on future Canadians for decisions made now. This generational burden shifting is a choice Ottawa is making. Both methods are acceptable...it is just a matter of society choosing who takes the responsibility. My article let's people see what choices are being made. That way each Canadian has the info to decide for themselves which method we should be using.

This is an excellent article and worth the time to read.

The question I have "Does an article like this reach the eyes of Political Masters?"

I suspect most of our MP's and MPP"s spend all their time reading reports on the economy and now COVID-19 and rarely if ever look at what is going on in the bureaucracy. Sad state of affairs.

This report deals with the details which are very important. Now we need to find a way of getting the government and industry to pay attention. We as citizens are handicapped in today's society as we spend way to much time listening to the Media and world news.

Somehow we must break this trend. Perhaps COVID-19 when it is finally defeated provides an opportunity to start a new sheet. A plan for attaching the Carbon Crisis is now critical and must be worked in with the plan to restart the economy and get people back to work.

Rough waters ahead for us all!!

The government knows what is happening. All the data in my article is government data. And the government has worked hard for years to find ways to push the carbon off the books. The government knows.

The public, however, doesn't know. You need to read the technical annexes to government emissions inventories to figure it out. It took me a month of reading docs and building spreadsheets and making reporter inquiries of Environment Canada to untangle it all.

The climate science is clear that all sources of excess CO2 have to be stopped in coming decades. That include forest carbon from forests in which more carbon is being removed than is growing back. No safe future for kids without turning off all the CO2 taps.

There is no mention in the article of the replanting of trees after logging and if it has been taken into account here. Replanting used to be a mandatory part of the permit process in BC.

That is an excellent question Ray. The government data used in my article and charts doesn't say how much forest is being replanted and whether replanted areas are net carbon absorbers.

This is excellent (and scary) infomation. Thank you. You noticed the forest isn't growing back, is that because of deforestation for agriculture? Are we shifting forest designations and usage from managed to agricultural uses?

Last summer I traveled across Alberta, Sasketchewan and Manitoba on the tourism designated "Lake and Woods Route" that is, the most northern east-west highways. All along that route agriculture is expanding, there are piles of wood-waste waiting to be burned away at the edge freshly deforested fields. While were were listening to the radio stories of Brazilian deforestation and Canada's response to the Trillion Trees initative and driving past acres and acres of newly deforested land every day it seems most odd that no one appears to be talking about the environmental impact of Canada's agricultural expansion.

I wonder, what impact the moving northern boundary for agricultural land makes on our forest's ability to absorb carbon, and who, if anyone, is responsible for the policy and regulatory control of this change?

IOW, our government is up to the usual: claiming "transparency" and engaging in sleight of hand.

Not only that, misrepresenting itself internationally by riding roughshod over agreements and commitments ... which many now recognize, having had strips torn off us by European friends and acquaintances, who seem to know a lot more about our governments' duplicity than we do, and somehow seem to think that we as individuals have consented to and agreed with such shenanigans.

Government bureaucrats know a lot, and offer political leaders policy "options." But most MPs and MPPs are kept busy helping individual constituents sort through bureaucratic bungling. Many vote on legislation without even knowing what's in it. I had that directly from the mouth of an elected representative, who also said they don't have enough resources to have their own people do the work. Some democracy, say wot?

Barry, your report is incredibly helpful in revealing the dynamics of Canada's forests in relation to Canada's carbon emissions, and incredibly distressing in revealing the climate hypocrisy of our federal government in reporting our corresponding carbon sequestration and emissions. My personal focus in forestry has been on (distressing) BC provincial policies and misplaced priorities. But your article points out a higher level of mismanagement : the federal requirements for reporting of carbon emissions in a way that intentionally excludes the largest percentage of emissions. Which ministry or ministries in the federal government are responsible for the carbon reporting?