Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

A COVID-19 outbreak from an oilsands camp in Alberta started spreading across Canada in mid-April.

It started with a few cases at a work camp housing thousands of fly-in, fly-out workers at Imperial Oil’s Kearl Lake facility, 70 kilometres north of Fort McMurray, Alta. When those employees headed home, the virus went with them.

By the end of April, workers from Kearl had unwittingly spread COVID-19 to a remote northern Saskatchewan Dene village, starting an outbreak that killed two elders, and into a long-term care home in British Columbia. Cases have also been reported in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador. The outbreak now spans 106 cases in five provinces, including Alberta.

Critics say the province could have prevented further outbreaks if it had restricted fly-in, fly-out work in the oilsands. Of the 106 cases linked to Kearl Lake, 24 are in other provinces.

“There’s absolutely no doubt that the Alberta government’s decision to not close down the camps, or at least put constraints on fly-in and fly-out operations, has cost lives,” said Alberta Federation of Labour president Gil McGowan, who wrote to the provincial government in April to ask for restrictions on fly-in, fly-out work. (The federation is an association of 29 unions.)

“It started with Kearl Lake,” said Rick Laliberte, the incident commander of the Northwest Incident Command Centre, a group of northern Saskatchewan First Nations, Métis and municipal leaders working to address the oilsands-linked outbreak in their region.

“Alberta didn’t contain it.”

In an emailed statement, Alberta Health spokesperson Tom McMillan said the province is not aware of any deaths that have been directly linked to Kearl Lake. (Cases such as the two elders who died in northern Saskatchewan aren’t considered direct links, as they didn’t contract the virus at Kearl Lake.)

McMillan also did not directly respond to questions about why Alberta hasn’t restricted fly-in, fly-out work during the pandemic.

“We are monitoring the situation in work camps closely to limit the spread of COVID-19 and protect the health of everyone involved,” he said.

Imperial Oil spokesperson Lisa Schmidt said the company has implemented new safety protocols and is working to support workers who have fallen ill. It started preparing for this outcome in mid-March and has tested all Kearl Lake employees, she said.

“We are following and have been implementing all guidance from public health authorities and instructing our workforce to follow all of the guidance of their local health authorities,” she said in an email.

Oilsands camps at heightened risk of spreading COVID-19

Even as much of Canada’s economy has ground to a halt, several provinces have deemed oil and gas work an essential service. The workforce at several oilsands sites is reduced, however, as companies cut production in response to plummeting crude prices.

Roughly 15 oilsands operations use fly-in, fly-out workers, according to a 2018 report from the Oil Sands Community Alliance.

These ‘rotational’ staff will often work at their job site for an extended number of days and then fly home between shifts — for example, two weeks on, one week off. Some companies have private aerodromes to bring workers to the site, where they’re often fed and housed in remote camps that can hold thousands of people.

Some critics have raised concerns about whether a fly-in workforce could spread COVID-19. In response, Alberta Premier Jason Kenney has noted that oilsands operations, many of which rely on rotational workers, can’t simply be shut down as that process can damage their equipment.

The close quarters at oilsands camps make it easy for COVID-19 to spread, said Dr. Ameeta Singh, an infectious disease specialist and clinical professor at the University of Alberta. But it’s doubly tricky because workers at the camps are coming and going.

“I think what’s a little bit unique to the oilsands situation is that people are moving in and out,” Dr. Singh said.

“Every time there’s movement like that, people are at risk of acquiring the infection and therefore potentially passing it on.”

As COVID-19 began escalating in Canada in mid-March, companies that operate oilsands camps — including Civeo, which services Kearl Lake — began implementing new safety measures in hopes of blocking the spread of the virus. But COVID-19 got in anyway.

McGowan wrote to the Alberta government on April 16, after the first cases at Kearl Lake had been announced, asking for the province to intervene and restrict movement to and from fly-in sites.

“We were concerned that the work camps would become almost cruise ships,” he said, referring to the vessels that became floating COVID-19 incubators during the early stages of the pandemic.

In a follow-up phone call, McGowan said the province said they were putting safety protocols in place. But Alberta didn't restrict the use of fly-in workers.

‘They’re oilsands-caused’

A week after the first case at Kearl Lake was publicly announced, B.C. provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry warned the oilsands outbreak had crossed the Alberta border. Some Kearl Lake workers passed the virus on to family members, including one person who was working in a long-term care home.

That transmission caused an outbreak at the home. B.C.’s Ministry of Health has not identified the facility, but told National Observer the cases there were not fatal and the outbreak at the long-term care facility is now over.

On April 17, the Alberta government said it gave contact information for infected people to provinces dealing with Kearl Lake infections.

But B.C. struggled to track down everyone in the province who had been at Kearl Lake, and Dr. Henry issued public pleas for those who worked at the site to self-isolate for 14 days.

“It has been a challenging process, as we don't all have contact information for everyone,” Dr. Henry said on April 28.

At least 16 COVID-19 cases in B.C. were linked to Kearl Lake, not including close contacts of workers who were carrying the virus.

Meanwhile, northwestern Saskatchewan has also become a COVID-19 hotspot after a Kearl Lake worker carried the virus home. Three cases in the area have been directly linked to the oilsands, the Saskatchewan Health Authority said.

In addition to the two elders who died, a third is in the ICU, Laliberte said. Non-essential travel in the region is now restricted.

The Dene village of La Loche, a community of 2,800 people located a six-hour drive north of Saskatoon, declared an outbreak on April 17. In the winter, an ice road connects La Loche to the oilsands, where many residents work.

The far north of the province, a region which includes La Loche and several other Indigenous communities, had reported more than 200 cases Monday. About 150 were active, making up the bulk of Saskatchewan’s remaining cases.

“As far as I know, they’re oilsands-caused,” Laliberte said.

Fighting the virus in northwestern Saskatchewan has been difficult and costly, Laliberte said. It was hard to get access to personal protective equipment, and many people need extra help, as they live in crowded conditions that make it difficult to self-isolate at home.

Remote First Nations are also already at higher risk from COVID-19 due to lack of access to health care and systemic inequities.

“We’re innocent,” Laliberte said. “No one asked for the virus and no one asked to spread it... Can we send the bill to Alberta?”

James Winkel, a spokesperson for the Saskatchewan Health Authority, said the province now has officials on the ground for “aggressive” contact tracing in a bid to slow the spread of the virus.

“Our results are paying off,” Winkel said in an email. “We’re seeing a lowering trend in the number of positive cases in La Loche, but at the same time expect some cases to arise as a result of the more aggressive testing underway in this area of the province.”

Saskatchewan has issued a “precautionary advisory” asking people returning from northern Alberta to self-isolate for 14 days. B.C. has ordered workers returning home from Kearl to self-isolate, as have Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia, which have reported one Kearl Lake-related case each.

Dr. Singh said based on case numbers alone, it appears that asking workers to self-isolate once they’re home isn’t working on its own. But the entire country is facing an unprecedented situation where people are having to balance economic concerns with health-related ones, and there are no one-size-fits-all answers, she added.

“Given that transmission has already been documented (from the oilsands), the question is what is the next level of measures that need to be taken,” she said. “We have to reassess on a daily basis, it seems.”

‘It’s an issue of political will’

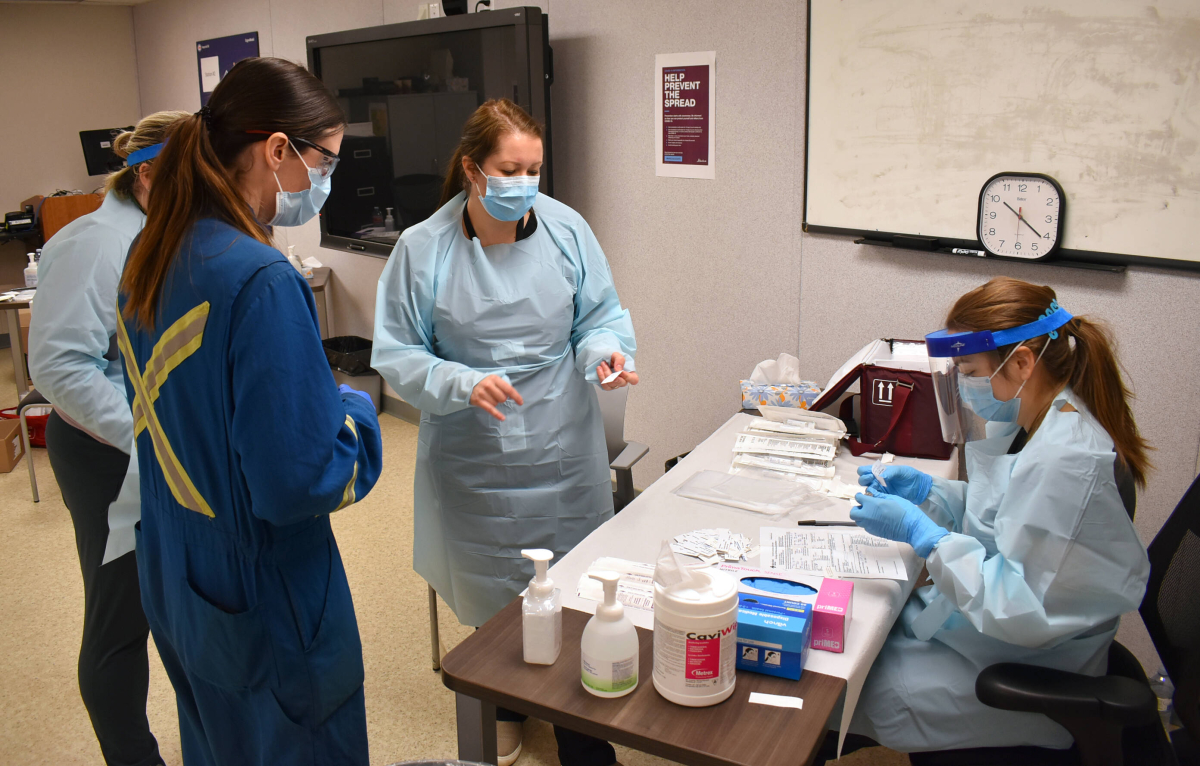

Of the 106 COVID-19 cases linked to Kearl Lake, 74 have since recovered. The Alberta government has also created a set of protocols to halt the spread of the virus in camps, including screening of workers, disinfection practices and changes that allow physical distancing.

When a worker tests positive, anyone on or offsite who may have been infected must immediately self-isolate for 14 days.

“The fact that the number of cases at Kearl are comparatively low after almost a month suggests control measures have been quite effective,” said McMillan, the Alberta Health spokesperson. The B.C. Ministry of Health said its officials had not drawn any conclusions about whether the Kearl Lake cases appear to be levelling off.

McGowan said the Kearl Lake outbreak has been managed better than Alberta’s other high-profile industrial COVID-19 hotspot, a Cargill meat plant south of Calgary that has the largest outbreak in Canada. But it still could have been handled better, he added.

“Here in Alberta, our province’s response to COVID-19 has been a story of success in the public and a failure in workplaces,” he said. “Infections never remain in the workplace, they’re also carried out into the community. So in that way, by failing to deal with workplace infections and outbreaks, our provincial government has essentially been undermining their attempts to stop the spread in the community.”

The Oil Sands Community Alliance, a division of the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers lobby group, says that fly-in workers are crucial in the oilsands. Some sites would be a 90-minute or even three-hour drive from Fort McMurray, and it would be impractical for them to commute by car every day.

McGowan said he doesn’t buy that workers from other provinces are necessary. There are plenty of out-of-work tradespeople in Alberta, he said, and limiting fly-in work could prevent infections from spreading outside the province.

“It’s an issue of political will and misplaced priorities,” he added.

“This needs to be driven home more, especially now as our province and other provinces consider reopening and sending people back to work.”

Meanwhile, two other oilsands operators have reported COVID-19 cases. Those aren’t considered ‘outbreaks’ as Alberta Health Services has not found evidence the virus was transmitted at the sites. Four cases were reported at a camp at Canadian Natural Resources Ltd.’s Horizon site, which uses rotational workers, while two were reported at Syncrude, which doesn’t have fly-in, fly-out staff.

Comments

The 'Alberta Advantage' raises it's ugly head again. This 'advantage' says that whatever benefits the fossils is good for everyone. NONSENSE. I remember signing a petition about a month ago that called for shutting down work camps in Alberta and B.C. At the time that was denounced as being too extreme.

Politics, disinformation, and nonsense coming out of Alberta leadership. You'd expect at a minimum they would at least accept responsibility and stop this nonsense. Instead they double down. Albertans are not going to be very welcome in BC this summer. Keep your money and stay home.

Because of tarsands pollution, the belligerent attitude of Albertans around everybody else "owing" them, and the sheer stupid wilfulness of the province's "leadership", people I know in BC who were 20 years ago wanting to join AB and SASK in an escape from Confederation, now tell me, "We don't want to be thought of as "like Alberta." We hate what they stand for."

Granted, most Albertans don't stand for the same values as Kenney and Scheer. They're just so used to Oil having put beef on the table for decades (and SUVs in the yard, and snowmobiles and all-terrain vehicles in the national parks), that it doesn't occur to them that, like Americans' view of their runaway-brand of capitalism, it's not that other people are jealous: they're angry at what's been taken from them ... you know, clean air, drinkable water, much lower cancer rates, etc. etc. etc. Oh yeah: and the possibilities of democracy!

I guess that's why the Pembina Institute calls it "responsible oilsands development."

AB's "ethical" oilsands industry is responsible for

• Rising greenhouse gas emissions and mounting climate change impacts

• Endangering health of indigenous communities

• Destruction of wildlife (not just birds) in toxic tailings ponds

• Extirpation of caribou

• Shooting and poisoning of 6000 wolves

• Destruction of wetlands and forest

• Displacement and loss of wildlife

• Contamination of the watershed

• Deformed fish with tumours and lesions

• Rare cancers in communities downstream

• Proposed export to Asia, increasing tanker traffic, risk of maritime disasters, and threat to marine species

• Acid rain

• Petcoke exports to developing nations —a cheap, lethal substitute for coal

• Obstructing climate action and rolling back environmental regulations

And now COVID-19 outbreaks.

Brought to you by your friends at Esso.