Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Humanity is hurtling towards a full-blown climate crisis. To avoid that dystopian future, all the world's countries joined together five years ago and signed the Paris Agreement.

Unfortunately, the initial climate targets pledged under it aren't nearly strong enough to deal with the intensifying climate emergency. So, a central part of the agreement is a ratcheting mechanism in which countries strengthen their climate targets every five years.

That's this year.

And the peer pressure to increase ambition is growing quickly.

For example, all of Canada's peers in the Group of Seven (G7) countries are on board. Some like the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, and the European Union have already submitted substantially stronger targets for 2030. Japan and the United States say they will as well.

In addition, the new Biden administration has started to lean in on the global diplomatic push. In just one of the many recent examples, John Kerry, the new U.S. special presidential envoy for climate, turned up the heat during his speech at the World Economic Forum: "All nations have to raise our sights together, or we all fail together. Our goal in Glasgow (the next UN climate meeting in November) is to see all major emitting countries together raise ambition — to not be content with goals 30 years from now, but to lay out road maps with benchmarks starting this year." In other words, countries that were planning to only pledge a numbingly distant net-zero 2050 target are going to be pushed to align their short-term targets with it as well.

And what about Canada?

When asked, Environment and Climate Change Canada confirmed Canada is also committed to strengthening its 2030 target this year.

It's certainly good news for the climate fight that all of the G7, plus the European Union, are now pledging to do more by 2030. These are the world's largest advanced economies. With just one sixth of the world population, they hold more than half the world's wealth, produce half the global GDP, and emit a third of the climate pollution.

In short, these are the countries with the most resources, talent, technology, and capacity to find and implement solutions for the climate emergency. And each still emits more climate pollution per person than the global average. So, if the world is going to prevent a climate tragedy, these countries have to lead the way.

The big question now is: How ambitious will these revised targets be? Will they align with what the science says is needed?

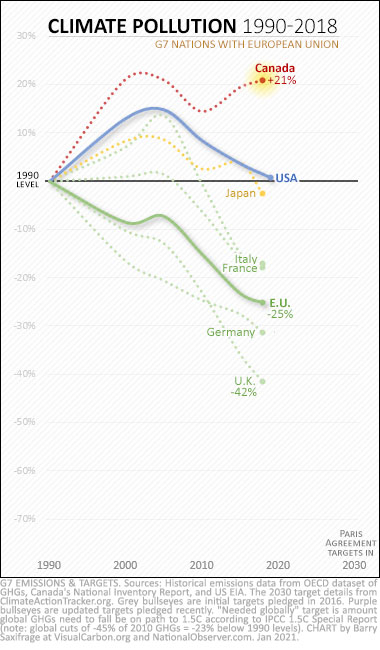

To provide an overview of the current situation and the choices ahead, I've created a series of charts covering the G7 plus the European Union. The first charts set the stage by showing you where Canada and its G7 peers are now with their climate emissions and targets. And then I'll add to the chart the new targets announced so far, plus a marker showing what the best climate science says is needed by 2030.

Past emissions

To see where each country is positioned today, let's look at past emissions.

My first chart shows the changes in climate pollution since 1990, the international baseline year for comparing emissions. Most lines end with 2018 because that's the most recent data available from those countries. The U.S. line ends in 2019.

As this first chart makes clear, Canada has been the rogue climate polluter in the group so far.

Despite promising since 1988 to reduce our oversized climate pollution, we've instead cranked it up.

We now find ourselves the only G7 member still polluting well above the 1990 starting line.

And take a look at the lines over the most recent decade — the years when the climate crisis started to hit with increasing fury. Every country lowered emissions over those 10 years except Canada. Ours went up. Our failure to keep pace has left us in a tough position.

The next poorest performers since 1990 have been the United States and Japan. Both emit roughly the same now as they did three decades ago.

The Europeans, in contrast, have reduced their emissions. The 27 countries of the European Union, as a whole, now emit one quarter less than they did in 1990. And our commonwealth peer, the U.K. — aided by its innovative and effective 2008 Carbon Budget law — has managed to cut its climate pollution by more than 40 per cent.

If the British can do it, Canadians can, too. What these European efforts highlight is that Canada's past climate failure has been a choice we've been making. Going forward, we can choose to be a climate leader instead.

Now that we've seen where each country has positioned itself, let's look at where they've pledged to go in the future.

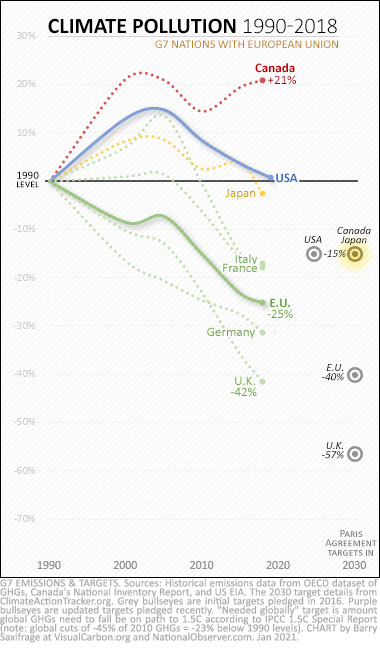

Paris climate targets — Round 1

As noted above, every major economy pledged an initial climate target five years ago as part of the global Paris Agreement.

I've updated my chart to mark initial targets with dark grey bull's-eyes. Germany, France, Italy and the other 24 countries of the European Union all share its single target.

As you can see, Canada and Japan pledged the weakest initial targets. They each promised only a 15 per cent reduction after 40 years.

The Americans pledged a similar tiny reduction, but promised to get there five years sooner, by 2025.

The European Union pledged 40 per cent below 1990. The U.K. targeted a 57 per cent reduction. And the British went the next step and legally bound its government to meet that.

It's worth pausing to note that achieving the European target of a 40 per cent reduction over 40 years only requires cutting pollution by one per cent each year.

It turns out that this is the same reduction rate Canada has been repeatedly promising over the last 30 years. For example, in 1988, the Mulroney government pledged to cut one per cent per year in Canada's first climate target. A decade later, the Chrétien government pledged the same rate with our Kyoto Accord target. And in 2009, the Harper government pledged that rate for our Copenhagen Accord target through 2020.

Just imagine where Canada would be now if we had lived up to those repeated promises of slow and steady progress? We'd have done a lot less climate damage. And we'd be facing a much less daunting transition task now.

But, unlike the Europeans, we didn't follow through. As a result, we've built up a vastly larger mountain of emissions to cut and now have only half as many years to accomplish our goals.

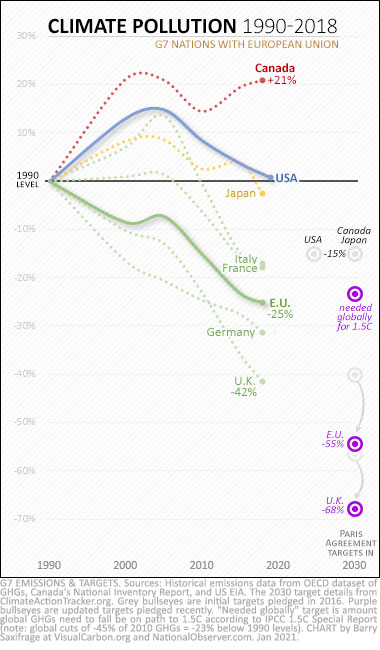

Round 2 — Increasing ambition

Now the pressure is on to strengthen those initial targets to align with what the best science says is needed to avoid a full-blown climate crisis.

Since all these countries plan to update their targets, I've faded the initial ones to a light grey. Then, I've added purple bull's-eyes showing the stronger targets that have already been pledged. I'll start at the bottom and work up.

The U.K. set the lowest new target, agreeing to reach 68 per cent below its 1990 levels.

And the European Union strengthened its 2030 target to a 55 per cent reduction.

The final purple target on the chart, labelled "needed globally," shows roughly where the latest and best science says global emissions will need to be in 2030 in order to limit warming to the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5 C. (For more details on this see the endnotes.)

Of course, the wealthiest countries with higher emissions per person and the greatest capabilities to act must do more than this if humanity is going to succeed.

So far, however, the initial targets of Japan, U.S. and Canada are much weaker than that global target. So, the pressure is on these countries to significantly strengthen their initial pledges and efforts.

Japan says it plans to strengthen its target this year. But it hasn't said by how much. According to the group Climate Action Tracker (CAT), Japan is already on track to "significantly overachieve" its initial target. CAT calculates that already "implemented policies will lead to emissions levels of 18 to 29 per cent below 1990 levels in 2030."

The Americans say they will announce a new 2030 target soon. It will be ready before the international climate summit President Joe Biden is putting together in April. They also haven't said how low they plan to aim for. But if the Americans plan to increase their ambition and lead by example, they will need to pledge something well below their current 2025 target.

And it is looking like they are indeed serious about increasing their ambition. Biden's climate plan states he "will lead an effort to get every major country to ramp up the ambition of their domestic climate targets."

To lead the charge, he appointed former Secretary of State John Kerry — one of the architects of the global Paris Agreement. Kerry started his new job by warning climate change is an "existential threat," and in his first speech said: "At the COP in November, all countries must raise ambition together — or we will all fail, together. Failure is not an option. And that’s why ambition is so important."

The American public appears to be on board, as well. A recent poll from just before the presidential election found that "79 per cent support the next U.S. president hosting a meeting of the leaders of large industrialized countries to urge them to do more to reduce global warming."

Which brings us to Canada. How much lower will Canada aim? Will we keep up with our G7 peers? Will we align with what the science says is needed?

Per person

One other common way to compare climate impacts and efforts across countries is on a per-person basis. So, for an additional insight into where the G7 countries find themselves today, I'll wrap up with a chart showing this.

As this chart makes clear, Americans and Canadians are the super-polluters in the group. Both emit 20 tonnes of climate pollution per person (tCO2) each year. That's twice as much as any other G7 country.

The Americans used to be much dirtier than us. But as the dashed boxes on the chart show, they've cleaned up more and are on track to pass us soon.

The rest of the G7 countries emit between seven and 10 tonnes per capita. That's still higher than the world average of six tonnes. But the British, French and Italians appear poised to move to the cleaner side of that line soon.

The U.K. has made the most progress per capita in the group. It has managed to cut its per-person emissions in half. Seven tonnes down, seven more to cut.

The Germans and Americans each cut five tonnes per capita, while the European Union overall cut four tonnes.

Canadians managed just two. At this rate — two tonnes every three decades — it will take us a century and a half to get our climate impact down to where the Europeans and Japanese are now.

However you slice it, the data shows Canada has been doing the least amongst our G7 peers in the fight to pass along a safe and sane climate.

But that could all change this year. Canada could finally choose to be the climate leader that the world needs us to be. We are one of the few countries with the resources, talent, and capacity to develop the solutions and make them happen at the scale needed.

If not now … when?

If we do decide to switch from climate rogue to leader, our youth will certainly thank us. A new global poll of teenagers found that Canadian and German teens top the charts, with 83 per cent calling the climate situation an "emergency."

They don't want to live in a climate-ravaged future.

Who would?

---------------------------------------------------------

ENDNOTES

Q: What's needed globally by 2030?

In one of the charts above, I placed a purple bull's-eye labelled "needed globally for 1.5C" at ~23 per cent below 1990 levels. Here's how I calculated that.

The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) produced a Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 C. It reviewed the best climate science on what it would take to limit global temperature rise to the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5 C. It concluded that global emissions needed to "decline by about 45 per cent from 2010 levels by 2030 (40 to 60 per cent interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050."

For global emissions, that "45 per cent below 2010" works out to 23 per cent below 1990 levels.

For those data geeks out there wondering what 45 per cent below each G7 country's 2010 emissions works out to, here's the list:

- Canada: 37 per cent below our 1990 emissions

- U.S.: 40 per cent below 1990

- Japan: 44 per cent below 1990

- Italy: 45 per cent below1990

- France: 48 per cent below 1990

- EU: 53 per cent below 1990

- U.K.: 58 per cent below 1990

- Germany: 59 per cent below 1990

It should be noted that these only match the average needed globally: "45 per cent below 2010." The Paris Agreement calls on countries that have the most resources and capability to do more than that global average. So, the G7 countries holding most of the world's wealth and with the most advanced economies capable of acting, would have to do more than this average if humanity is to limit warming to 1.5 C.

Q: What is the "fair share" for each country?

You may have noticed I didn't talk about "fair share" in my article. I instead stuck to the more limited issue of what is required for humanity to succeed.

That's because there are so many opinions on what constitutes each country's "fair share." And I can personally see merits in many of them.

Because it's a topic many are interested in, I've included a short discussion here in the endnotes, along with a couple of links to dig deeper if you're interested.

One widely followed "fair share" calculation is from the group Climate Action Tracker (CAT). It rates each country's targets based on criteria it sees as "fair." For example, it rates Canada's initial 2030 target as "insufficient." And it calculates that Canada's fair share of meeting the 1.5 C goal would be to cut emissions 45 per cent below 1990 by 2030.

Again, that's just one of the many "fair share" calculations out there. To get a flavour of how broad the range is, here's a summary of several proposed "fair share" targets for the U.S. in 2030. They range from cuts of 45 per cent all the way to cuts of nearly 200 per cent. Achieving more than 100 per cent would be done by helping other countries reduce their emissions.

Comments

A good article on where the countries stand on climate reduction in so far as the G7 countries are concerned.

Question: What are the figures for China, Russia, Iran, Israel and Brazil to name a few.

I raise this as a question only, not looking for any reason to argue against the G7 numbers.

My observation of the Canada plan, is there is not a measurable plan in place, only words. The government needs to put some teeth in place similar to what the UK has done.

The government needs to show us some numbers for the amount of reduction due to the Carbon Tax. I doubt they can provide accurate numbers in this area from what I've read so far.

As a Canadian I can only reduce my foot print by cutting use of fossil fuels, waste as much as possible. Without any way to measure this I have no idea how well I might be doing.

In my opinion he Federal and Provincial Governments deal in nice words, lofty goals and no concrete measurable plan to achieve Carbon reduction.

Yeah, individual action only goes so far. For instance, my house and water, like most, are heated with natural gas. I could change to electrical heating, but the expense both for a new heater and simply because electric heating is currently more expensive than gas, is prohibitive. So if we're going to change from fossil fuel heating to electric heating, the government needs to step in--subsidize the electric heaters and tax the natural gas and help the electric heater installation ramp up.

There's a host of other society-level, government actions that are needed, from building transit to construction standards. Consumers can't do all that stuff. Although I will say I have no regrets about having bought an electric car . . . but even there, government subsidies certainly helped.

I agree that individual action is only part of the picture. It's a critical part because government rarely lead...so it takes a critical mass of the public forging ahead to give politicians the support needed to require larger changes. But in the end, govts have to change the incentives for a transition to happen in time. Not either/or...both.

I always find your analyses interesting - please keep them coming! Would be interested to see a chart showing the same countries' per-capita emissions from 1990 to 2020.

Thanks for your comment. The article does have a bar chart at the end showing per-capita emissions, but I think you talking about a line chart similar to the one for total emissions. That would be interesting. I didn't take the extra time to create one like that so I can't say for sure, but I would expect the countries to generally follow the same pattern as in their total emissions line -- except more steeply down because per-capita emissions are falling faster than total emissions.

I'd be interested in seeing where on those graphs the country "Canada minus Alberta and Saskatchewan" would fit. From what I've read, including here, it seems like if it weren't for their massive ramp-up of emissions we wouldn't be doing all that bad (although still not good enough). Which points to certain low-hanging fruit, or rather hunks of tar, we could get a lot of progress out of eliminating.

Yes, I've written about that topic several times. Here's one from about a year ago with lots of data and charts about it: https://www.nationalobserver.com/2019/11/27/analysis/wexit-and-climate-…

The short answer is that emissions in "Canada minus Alberta and SK" were -5% below 1990 in 2018. That's below USA and Japan but not as low as the G7 Europeans nations. And per capita it's around 13 tCO2 each which is still higher than any G7 except USA. So much of Canada is lower-carbon than our national averages suggest, but even those areas are certainly not enough great. Lots more to do all across Canada.

Very interesting: I too would be interested in learning more about what sectors are contributing most to Canada's performance, and then in seeing relevant comparisons with G7 countries for the laggard sectors. Is it transportation, or heating, or is it (just) resource extraction?

Those are good questions. To give you a sense of where our per-capita emissions come from, here are Canada's sectors in 2018:

5.2 tCO2 Oil & Gas production

5.0 tCO2 Transportation

2.5 tCO2 Buildings

2.1 tCO2 Heavy Industry

2.0 tCO2 Agriculture

1.7 tCO2 Electricity

0.6 tCO2 Light industry

0.5 tCO2 Waste

...You can see that two sectors, Transportation and Oil & Gas, add up to over 10 tCO2 which is more than half of Canadian total and alone exceeds what the Europeans emit in total. One of the reasons our Transportation emissions are so high is that Canadians choose to buy the world's most climate polluting cars and trucks: https://www.nationalobserver.com/2019/09/04/analysis/canadian-cars-are-…

Agreed that Canada as a state and we as individuals should do more to reduce ourCO2 footprint. The climate is global, so the contribution of CO2 in absolute amounts is also important. Individually we are down 2% and although Canada's +21% sounds disastrous, in absolute terms our CO2 production is a drop in the ocean compared to China, USA and the EU, or even the UK. Or if you want to compare individuals, include Saudia Arabia per capita. Adding a 5th graph, giga tonnes per state would add reality to the analysis. It also ignores starting points - phasing out coal for natural gas (EU, UK) is an easy win compared to a country that already generates most of its electricity from hydro (Canada).

We should all do our parts by getting off CO2 intensive energy sources as soon as possible, but we should be aware that we are small fish in the sea of polluters. We can behave morally in this context without beating ourselves up for not wearing a hair shirt.

Well, you aren't the only one to claim that your country's contribution is so tiny as to not matter much. Even John Kerry in a recent speech emphasized that 90% of global emissions come from outside the US, so they can only do so much on their own. Out of ~200 countries in the world, Canada manages to be in the dirty dozen list for *both* total emissions and per capita emissions. Just us and the Yanks.

Regarding being a "drop in the ocean compared to UK", that used to be true. They have nearly 2x people and much bigger economy so back in 1990 it isn't surprising that they emitted 200 MtCO2 more than we did (800 vs 600). But not anymore, now they emit 280 MtCO2 less than us (450 v 730). If you want to see just how different these two Commonwealth peers have done with their emissions: https://www.nationalobserver.com/2020/05/29/opinion/canadas-emissions-r…

You know when I read something like we are small fish and our pollution is nothing. I really think this is very counterproductive . It gives some Canadians a pass, in their minds. I’ve heard the argument , personally, from Canadians not interested in acknowledging that they and we are all part of a larger world crisis. It engenders a sense of entitlement , a 1% mentality if you will.

It’s not how much we contribute on a world scale it’s the fact we are and are seen to be pulling with the others.

I hope we are able to at least pick off the low hanging fruit, the elephant in the room.

That first chart in the article is an embarrassment to me, as a Canadian.

Good points. As Seth Klein points out in his excellent new book ("The Good War, Mobilizing Canada for the Climate Emergency"), Canadians contributed 2% of the allied war effort but it was a critical part of what was needed. Most Canadians are proud that we did what we could despite it being "only 2%" and not enough to win the war on our own. Canadians also joined the war long before the Americans. We didn't wait for them before we did the right thing.

Thanks for you analysis Barry. I always look forward to reading how you have pulled together the available data in an incredibly interesting and accessible way. In no way do I want to justify Canada's poor performance but I do want to point out that the big 'success' that the EU and the UK have had is in a large part related to conversion of coal fired plants to woody biomass. That is, they are burning all those wood chips that they get from the southeastern US, Canada and their own forests and claiming them as renewable energy with zero emissions. This accounting is questionable at best, given the emissions we don't count from burning woody biomass, the questionable assumption that biomass burning is net-zero because the trees will sequester carbon when they are replanted (which of course actually takes decades to longer to replace the carbon), and the huge impact on biodiversity that cutting down forests for biomass burning has. The world is a complicated place, including what we do and do not count in carbon accounting. Would be great to see you put your amazing talents with visualizing data to work on the issue of carbon accounting, including what UNFCCC allows and what is actually released. Keep up your great work.

Again, when we point the finger at other countries for creative accounting and accuse them of cheating this is not the point and trying to change the message does not help solve our very big problem in producing greenhouse gases.

Confusing the message is a well known strategy for climate deniers in their never ending attempt to instill doubt and stalling progress in cleaning up the mess.

Resist helping them . Stay on message .

The recently proposed Net Zero Accountability Act (Bill C-12) is where we need to be casting our attention if we want to secure an adequate 2030 target. While the bill is a first in Canada to set climate targets into law, it has been widely criticized for being too little, too late. Despite scientists naming this decade the most critical for emissions reduction to hold warming to a safe 1.5 degrees, the bill fails to adopt a 2030 target in line with IPCC recommendations and enshrine it into law. It also leaves out 2025 as a milestone target, opting instead to start 5 year milestones in 2030. We know from the 2018 1PCC report that in order to have a chance at a liveable world where warming is held to 1.5 degrees, we must cut emissions by 45% below 2010 levels by 2030, in addition to achieving net-zero by 2050. Without cutting emissions in half this decade, we have no chance at holding warming to 1.5 degrees, even if the 2050 net zero target is met, and the consequences will be catastrophic.

The Net Zero Emissions Accountability Act is Canada’s chance to finally put us on a safe climate trajectory, but only if the bill is amended to be stronger with science-backed targets and timelines. We will only secure the amendments we so desperately need if there is adequate public pressure. If there was ever a time to call and write to your MP, this is it. Will enough Canadians stand up and demand better? For the sake of my kid, I hope so.

These have gotten so tiresome to read over the decades, because none of it ever happens. By having targets for final outcome (lower carbon, somehow), you can never point to a project that is going badly, only mourn the total lack of progress some years later.

You need targets like "reducing air travel" and "gaining public transit riders" that you can actually watch. Or ideas like "cars should weigh less", and add taxes on buying an SUV instead of a Smart Car. How are we supposed to do all this reduction, if nobody ever sets a "target" for gasoline consumption per person?

It's all too vague for me. I should go read some more Vaclav Smil, that guy is highly specific and crunches numbers.

Our prime Minister smiles and smiles, yet he lies

There should be no limit to his/our ambitions to tackles climate crisis. Ambitions usually imply that they will fall short - as we have done so lamentably

Our ambitions must be boundless - because there is much of the planet that has NO ambition, neither the means, nor the interest in curbing the climate emergency. either through greed, power mongering, or fatalism Inshalla....