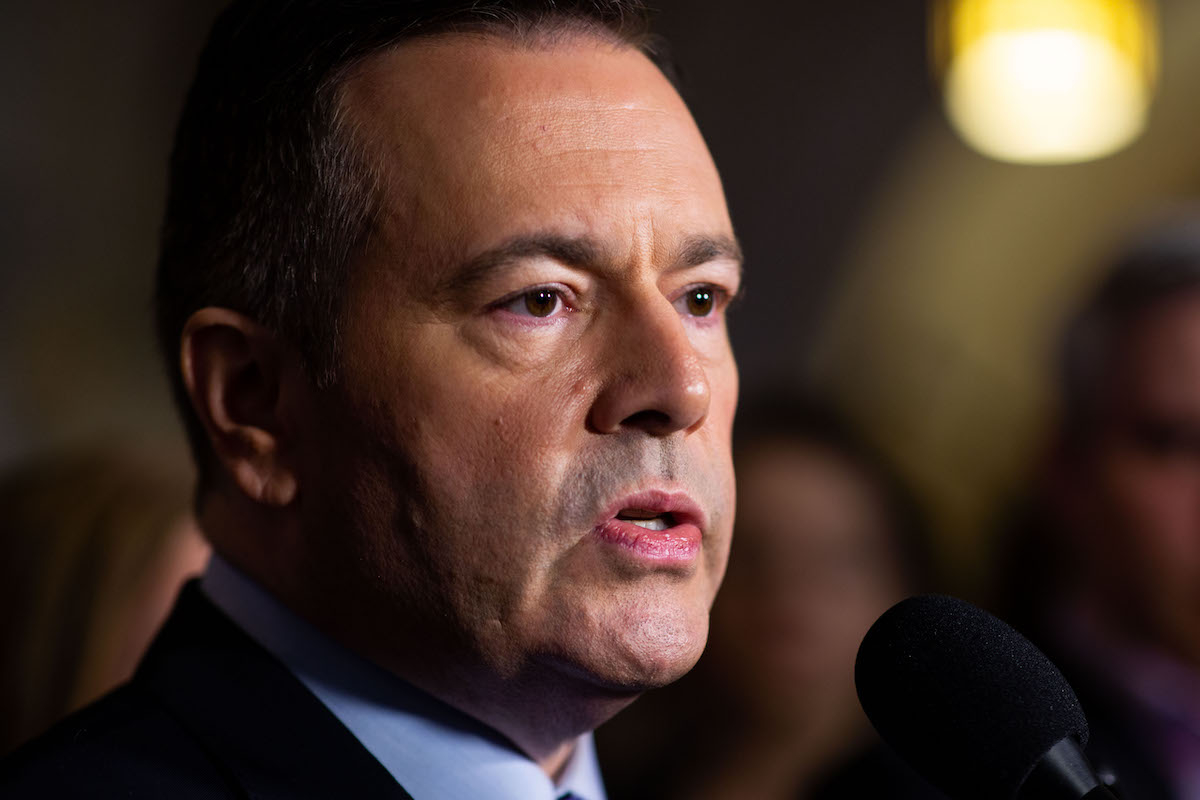

The fall of Jason Kenney

Jason Kenney was pissed.

On Jan. 20, the Alberta premier walked into a press conference at the legislature in Edmonton, making a beeline to a podium that bore a sign reading “Standing up for Alberta.” Wearing a dusky navy blue suit and matching tie, Kenney was responding to breaking news that U.S. President Joe Biden had just cancelled the Keystone XL pipeline, which was to carry oil from Alberta to Nebraska.

“This is a gut punch for the Canadian and Alberta economies,” said Kenney. “Sadly, it’s an insult directed at the United States’ most important ally and trading partner.” The premier said up to 2,000 unionized workers had just lost their jobs and if the Biden administration was unwilling to discuss the matter, “it’s clear the government of Canada must impose trade and economic sanctions” against the U.S.

For Kenney, news of the cancellation was one of a series of body blows his United Conservative Party (UCP) government has suffered over the past year and could not have come at a worse time. Already swimming in debt, the province had invested $1.5-billion in Keystone. More importantly, Kenney has gambled most of his political capital on rescuing Alberta’s ailing economy by resuscitating the oil and gas sector.

Now that strategy lies in tatters. As one former UCP staffer told me: “Reality is catching up with the province. It sounded good, in theory, but now we're getting our results.”

'Left in the dust'

“I think Jason Kenney is vulnerable because he ran on a platform that was based in his imagination and based in taking Alberta back to the ‘80s,” says Kevin Taft, a former leader of Alberta’s Liberal Party. “It was a series of promises that look backwards and refused to take into account the reality of a changing world… and Jason Kenney's platform is being left in the dust. So he’s ended up pouring billions of dollars of subsidies into the oil industry to try to prop it up while he's driving the Alberta government into staggering levels of debt.”

Kenney’s problems don’t end with Alberta’s faltering energy sector: largely due to his mishandling of the pandemic, Alberta now boasts the third highest number of COVID-19 cases in the country, and second highest rate per capita.

Then, over the Christmas holidays, it was discovered Kenney’s minister of municipal affairs, his chief of staff and five other UCP MLAs had travelled abroad, mostly for vacations (the minister had gone to Hawaii). When this news broke, Kenney refused to act. Even MLAs in his own party were outraged: Michaela Glasgo, who represents Brooks-Medicine Hat, said her travelling UCP colleagues showed a “profound lack of judgment” and urged Kenney to reprimand them.

Reluctantly, as public anger grew, Kenney punished the offending MLAs, accepted the minister’s resignation and fired his chief of staff. One MLA, Pat Rehn, who had flown to Mexico for a vacation, was thrown out of caucus altogether after complaints emerged that he rarely travelled to his riding and was ill-prepared when he did.

Since becoming premier in April 2019, Kenney has been hit by a torrent of mostly self-inflicted scandals. As a result, Kenney has gone from being one of the most popular premiers in Canada to one of its most disliked.

A poll commissioned by the conservative news website Western Standard last month said only 26 per cent of Albertans would vote for the UCP — as opposed to 41 per cent for the NDP. “Kenney’s UCP would face decimation if an election was held today with the NDP’s Rachel Notley returned as premier,” the site noted. In another poll, Western Standard found 41 per cent want Kenney to resign.

Indeed, Calgary Sun columnist Rick Bell recently opined on the MLA vacation scandal: “Is he really this tone-deaf? Or is it a case of Kenney really not thinking any of what’s gone on is that out of line?”

Even within the UCP, people are worried. The former UCP staffer I spoke to, who recently left government, says: “Definitely, people are upset right now with how things are going.”

“Kenney doesn't really understand the province and has antagonized almost every conservative group,” remarks Andrew Nikiforuk, an author and contributing editor at The Tyee who lives in southern Alberta and has written extensively on energy, economics and the West. “I don't think he will get re-elected in two years’ time — I think he's a one-term premier.”

If so, this would be a stunning fall for someone who is arguably the conservative movement’s biggest star. Prior to becoming premier of Alberta, the 52-year-old Kenney was one of Stephen Harper’s most highly regarded cabinet ministers — with rumours of him eventually eyeing a run for prime minister.

Ironically, Kenney’s troubles might lie in the fact he’s adopted Harper’s style of governance — and still takes advice from the former prime minister. Five years ago, Harper moved back to Alberta and runs a consulting business in Calgary. The premier appointed Harper to an economic advisory council and hired Harper’s son Ben as a policy adviser last fall.

“Harper is still a giant factor,” the former UCP staffer told me. “(Harper) was active in (Kenney’s UCP) leadership wins. He and his people — they never left. They are there.

“Kenney learned from Harper. If it worked (federally) and won a few elections, why is he going to do anything different? But it’s an old playbook by now.”

Like Harper and the federal Tories, Kenney and the UCP have embraced a style that veers towards the aggressive, unapologetic and authoritarian, laced with disinformation and picking fights that make little sense.

“They're incredibly arrogant,” says Laurie Adkin, a political scientist at the University of Alberta. “They think that they can do anything and will always get elected.”

For example, Kenney went to war with Alberta’s medical profession just as COVID-19 struck the province. A year ago, the government arbitrarily tore up the master agreement with the Alberta Medical Association in order to cut the pay of doctors. Last fall, the government announced up to 11,000 layoffs in the province’s health-care system — jobs slated to be privatized. Soon afterwards, a wildcat strike broke out among hospital workers. Now doctors are threatening to leave the province.

“The base of support for the (UCP) is rural Alberta, and that's where the fight took place, with rural doctors, much more so than urban doctors,” says Duane Bratt, a political scientist at Mount Royal University in Calgary. “(Albertans) like their social programs, they like their health-care system. And especially in a pandemic, you may think that doctors are overpaid, but you like your local doctor.”

By most accounts, when the first wave of COVID-19 hit, the Alberta government reacted responsibly. But when the second wave struck last fall, Kenney delayed closing down the province. As a result, the number of COVID-19 cases shot up, hitting more than 1,800 a day at one point in December - a rate higher than Ontario and Quebec.

Kenney refused to take ownership. When he was asked during a radio interview whether he accepted any personal responsibility for an approach that possibly cost hundreds of lives, Kenney went on the attack. "You have just joined the folks who are doing drive-by smears on Alberta," he said to the reporter. When it was suggested his government’s record was among the worst in the country for handling the second wave, Kenney replied: “I don’t accept the Alberta-bashing that is going on here” and argued that death rates in Alberta were lower than in Ontario and Quebec.

Moreover, the Globe and Mail reported in December that a source said Alberta has requested less than 10 per cent of the maximum amount the province could have asked for under Ottawa’s program for topping up the wages of low-income essential workers. The $30 million Alberta received from Ottawa is significantly less than the province could have requested — a total of about $347 million.

'A dyed-in-the-wool new right conservative'

“I know Jason Kenney, and so none of this is a surprise to me,” remarks Doug Griffiths, a former Tory MLA and cabinet minister in Alison Redford’s Progressive Conservative government. Griffiths met Kenney when Kenney was a federal minister. “All he wants is power. It’s about power and being in charge, it’s never been about what’s good for people, it's never been about what's good for the country, it's never been about what's good for Alberta.”

Kenney was born in Oakville, Ont., son of a private school headmaster who moved his family to Saskatchewan when Kenney was a boy. Kenney was raised Anglican but later converted to Catholicism.

“I take the teachings of my church pretty seriously when it comes to applying them to myself,” he once said.

Kenney was a political nerd and initially a Liberal Party supporter, working as an aide to Ralph Goodale in the early ‘80s. But his aggressive tactics first emerged when he went to study at the St. Ignatius Institute at the University of San Francisco, a private Jesuit university, in 1987.

One day in 1989, three members of the Women’s Law Student Association set up a table on campus to collect signatures for a pro-choice petition. One media account says Kenney and a group of male students surrounded the women, telling them to clear out, which they did (Kenney has said he was not among the men). Kenney then introduced a motion at the student senate to demand the university suspend the law association’s charter, which passed by one vote. “We’re playing hardball,” he told the San Francisco Chronicle, equating the pro-choice activists with supporters of pedophilia and the KKK.

The decision split the campus and sparked the threat of a lawsuit from the American Civil Liberties Union, forcing the university administration to pass a policy asserting the right of students to free speech. Kenney then led a charge to have the university removed as a Catholic institution.

While in San Francisco, Kenney volunteered at a hospice, helping out with AIDS patients. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors had voted in favour of domestic partner legislation, which would have allowed hospital visitation rights to same-sex couples — especially significant during the AIDS crisis.

Yet Kenney was involved in a petition spearheaded by Catholics to hold a referendum to overturn the law. In a speech he gave in 2000, Kenney boasted of his role, "which led to a referendum which overturned the first gay spousal law in North America.” When the referendum succeeded, it meant visitation rights for gay people whose partners were dying in hospices could now be denied.

Kenney has long opposed extending equal rights to the LGBTQ community. In 2005, he lobbied and voted against the federal law approving gay marriage, telling one media outlet it was okay to discriminate againt homosexuals. Immediately after becoming premier of Alberta, Kenney passed a law that stripped many protections for LGBTQ students in the school system.

Yet his opposition to gay rights has raised curiousity about his own sexuality. In 2017, Canadian singer k.d. lang, who is a lesbian, tweeted to Kenney: "You're gay aren't you?" To this day, Kenney has never been publicly associated with a partner, either male or female.

After deciding against returning to complete his final year at university, Kenney moved to Alberta. He soon became head of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, where he continued his confrontational tactics. Kenney became close to a group of hard-right young conservatives, including Ezra Levant.

“Kenney is a dyed-in-the-wool new right conservative,” says Jared Wesley, a political scientist at the University of Alberta. Wesley says Kenney embodies three aspects of the new right: neoliberalism, libertarianism and social conservativism.

“There’s this whole kind of cabal of these guys who are real fundamentalists... and they embrace this notion of a much harder, much more sharp ideological position,” says Dimitry Anastakis, a historian at the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto. Michael Coren, a former conservative TV host and writer who occasionally socialized with Kenney, says Kenney is of a generation of conservatives “who absolutely detest what happened before with the Progressive Conservative Party” — seeing it as too moderate. “They despise that. They think there is an ‘Albany Club attitude’ they refer to. They see that as wasted years.”

Kenney has always distinguished himself as a tireless worker who does his homework. Elizabeth May, who was elected as a Green Party MP in 2011, struck up a friendly relationship with Kenney and recalls he was not to be toyed with in a debate.

“He’s the only minister who stayed in the house all the time and was on his feet to eviscerate opposition MPs who were casual in their attacks on his legislation,” she recalls. “He knew his files, which a lot of ministers don't to this day, but he really knew what he was working on.”

From 'Snack Pack' to Conservative star

Kenney was first elected to Parliament in 1997 after catching the attention of Preston Manning, who recruited him to run for the Reform Party. Kenney emerged as the leader of a rambunctious band of young MPs dubbed Reform’s “Snack Pack.”

In 2003, Harper brought the warring factions of the right together under the new Conservative Party of Canada banner. Three years later, Harper won power, with Kenney becoming his parliamentary secretary. Soon Kenney established himself as an important asset to Harper: The Tory brain trust realized that many recent immigrants to Canada were social conservatives, opposed to abortion and gay marriage. Kenney was tasked to woo these voters.

“He was one of the spark plugs in terms of broadening the base of the Conservative Party beyond the normal kind of small town, white, high school-educated, rural base that we have had across Canada into something which was a bit more reflective of diversity in the country,” says former Tory senator Hugh Segal. Kenney’s outreach is often credited with helping Harper win his majority in 2011.

Harper rewarded Kenney with a series of important cabinet posts — immigration, employment and defence.

Yet his tenure as a cabinet minister was often controversial, especially as minister of immigration. “The overall legacy of Jason Kenney as minister of immigration was very politicized,” says May.

Kenney imposed a ban on niqabs at citizenship ceremonies, sided with Israel against critics of the Palestinian occupation, barred British MP George Galloway from entering Canada and crafted a bill ostensibly aimed at human smuggling that was so sweeping the B.C. Supreme Court sent it back to Parliament for redrafting, pointing out that it could have convicted human rights workers. Kenney also targeted Roma refugees fleeing an increasingly racist and violent Hungary, denying them entry into Canada. He claimed such refugees were “bogus.” Kenney even froze all immigration applications from parents or grandparents for two years.

Kenney did help some persecuted religious groups and even gay people facing harassment in certain countries. May recalls he was willing to help out refugee claimants on an individual basis she brought to his attention. Overall, though, she says Kenney took a punitive approach. “To tell somebody that you're being deported because your parents messed up your immigration papers when you were six months old, and it's too late for us to do anything to help you and you're out... There were a lot of individual cases that were just devastating.”

By early 2015, Kenny had amassed a war chest, possibly to take a run for the leadership of the Tory party if Harper stepped aside before the election. Harper squashed that possibility, leading his party to defeat. By then, Kenney was exhausted, having spent years crisscrossing the country as well as taking on challenging portfolios. Still, he was considered the second most important Conservative figure after Harper.

Surprisingly, he chose not to make a run for the leadership after Harper stepped down. “He could have easily won it, including in the last leadership contest,” says former Tory MP Dean Del Mastro, who was once friends with Kenney. “Nobody could have defeated him, that's just the fact of it.”

Back in Alberta, he saw a divided conservative movement that had led to the NDP's surprise victory in 2015, making Rachel Notley premier. The right was split between the ailing PC and more radical Wildrose parties. In 2016, Kenney decided to reunite Alberta’s right and make a run for premier.

However, Kenney was returning to an Alberta in distress.

After peaking at US$107 a barrel in the summer of 2014, petroleum prices fell to under $30 by early 2016.

“This resulted in a recession in Alberta in 2015 and 2016,” says Omar Abdelrahman, an economist with the TD Bank. “And even before the pandemic, Alberta was still not at a point where it had recouped all the losses from that recession.”

Given that the oilsands are one of the most expensive sources of petroleum, the collapse in oil prices had a devastating impact on the province’s employment and investment picture: By last year, an estimated 35,000 to 40,000 oil and gas extraction jobs had disappeared. “The thinking is it needs to be $50-$60 (a barrel) for (the oilsands) not to lose money,” says Keith Stewart, Greenpeace Canada’s energy analyst. “But their problem is that for new investment, it has to be even higher.”

Also threatening the oilsands is a growing divestment movement, with more than US$6 trillion being committed to divest from fossil fuels. Global banks such as HSBC, the world's largest asset manager BlackRock, insurance giant The Hartford, BNP Paribas, Société Générale, Norway's sovereign wealth fund, insurance companies and major pension plans have pulled investment from the oilsands. Even large oil companies like Shell have followed suit. The result was Moody's downgrading the creditworthiness of Alberta's debt to its lowest level in 20 years.

Uniting Alberta's conservatives

In 2017, with more than 75 per cent of the delegate votes on the first ballot, Kenney was elected leader of the PC Party of Alberta. That summer, he negotiated a merger with Wildrose, creating the UCP. He was soon leader of the UCP and won a seat in the Alberta legislature.

But the UCP would not be a centrist party. “All the progressive ideas came out — policies that would focus on the future, policies that would focus on new technology, policies focused on changing industries,” says Griffiths, who spent his political career with the PC party.

Kenney’s run for the UCP leadership was also tainted. In what is now known as the “kamikaze” scandal, Kenney’s camp is accused of putting up a stalking horse candidate, Jeff Callaway, whose job was to attack Kenney’s biggest rival — Brian Jean, leader of the Wildrose Party. Documents obtained by the media show Kenney's campaign proposed major aspects of Callaway's operation, including providing strategic plans, attack ads, speeches and talking points intended to discredit Jean.

Callaway's former communications manager, Cameron Davies, said Kenney attended a meeting at Callaway's house in July 2017 where the “kamikaze campaign” was discussed and Kenney had first-hand knowledge of this strategy. Kenney has denied any involvement in the scandal, while Callaway went to court to have the investigation shut down (which failed).

Another allegation is over whether Kenney’s camp fraudulently manufactured votes. CBC and CTV received documents indicating that fake email addresses attached to party memberships were used to cast ballots in the party's leadership race. Prab Gill, a former UCP MLA, has made the same allegation. Kenney has denied involvement in this scandal as well.

Moreover, top Kenney and Harper operatives have been attached to the controversies, including Matt Wolf, Kenney’s director of his war room during the 2019 election, and Shuvaloy Majumdar, the global director of Stephen Harper’s consulting firm.

After these allegations emerged, the RCMP and Alberta’s election commissioner opened investigations.

In the run-up to the 2019 provincial election, the UCP adopted a “fight back” strategy designed to convince voters that Alberta’s economic problems could be solved with a more belligerent defence of the oil patch.

Kenney and the UCP decided to blame the province’s woes on environmentalists and the Trudeau government. “This was not their main problem,” argues Stewart. “The main problem is (the oilsands) are high-cost carbon in a world that's moving to a low-carbon economy. But that was inconvenient. So they had a convenient scapegoat.”

Kenney even targeted individual environmentalists, such as former Pembina Institute executive director Ed Whittingham, who had accepted a seat on the board of the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER), although Whittingham and Pembina had a track record of working with the oil industry. The UCP and Kenney issued press releases and tweets targeting Whittingham. He quickly resigned from the AER and Kenney applauded, saying he would have fired him in any event.

Wesley, the University of Alberta political scientist, says after conducting polling of voters, he gleaned that Albertans viewed Kenney as a bit of a pompous jerk. “Albertans knew what they were getting,” says Wesley. “That’s what came through in our focus groups. But in 2019 they seemed to want a bully. I think Albertans were a bit ticked and wanted to take on the rest of the world, wanted to take on environmentalists, wanted to take on Trudeau, and they wanted somebody who was kind of — I won't say a strong man — but a forceful personality like Jason Kenney.”

In April 2019, the UCP swept to power, winning 63 of the legislature's 87 seats and 55 per cent of the vote. On election night, Bratt, the Mount Royal University political scientist, was working for Global TV at Kenney’s headquarters. “A couple of things that struck me over the course of that night,” he recalls. “This is a big victory celebration, they have just returned to government. But there was still a lot of anger in the room. Like this wasn't a happy group, this was an angry group. Even when they were winning, it was an angry group.”

The 'energy war room'

After his win, Kenney moved to squash the investigations into his leadership race. He fired Alberta’s election commissioner who was investigating Kenney and the UCP, including over the “kamikaze” campaign.

Kenney embarked on what he promised — attacking the environmental movement and Trudeau, especially over carbon taxes. He began labelling any criticisms of the oilsands “Alberta bashing.” A month after getting elected as premier, he visited the editorial board of the Globe and Mail where he was asked about investors’ concerns about emissions and climate change: he dismissed them as “flavour of the day.”

He then set up a public inquiry into the “foreign funding” of oilsands critics. For an initial outlay of $2.5 million, he hired Steve Allan, a member of Alberta’s business establishment, to lead the inquiry.

This contract amplified the allegations of cronyism that have dogged Kenney. Allan quickly awarded a $905,000 untendered contract to Dentons, the world’s largest law firm, for legal advice. Allan’s son Toby is a partner at Dentons. Moreover, Allan owed his appointment to Alberta’s first justice minister, Doug Schweitzer, also a former partner at Dentons (Allan had donated $1,000 and campaigned for Schweitzer in 2017 when Schweitzer made a run for the UCP leadership).

Dentons has an enormous roster of oil industry corporate clients, including Enbridge, BP Canada and Total. And Stephen Harper’s consulting business is run out of Denton’s Calgary offices.

Allan then refused to hold public hearings. His final report has been delayed three times, with Kenny adding another $1 million to the budget. In January, the inquiry posted three reports it had commissioned for nearly $100,000 from outside experts, of which one was authored by a well-known global warming skeptic who’s taken money from the oil industry, and another who spun a web of conspiracy theories.

Kenney also created an “energy war room” designed to attack journalists and critics of the oilsands and burnish the image of the energy sector. It was initially budgeted $120 million over four years and, from its inception, elicited highly personal attacks. On opening day, a supporter held up a poster with a photograph of environmentalist Tzeporah Berman. The sign had a red cross through Berman and was labelled “Enemy of the oilsands.”

Berman is the international program director of the environmental organization Stand.earth and had advised the Notley government up until 2017. “(Kenney) ran a pretty harsh campaign against me,” says Berman. “Every time he attacked me online, I would receive death threats and really misogynist and horrible attacks online, and that went on for the better part of a year.”

Yet the war room soon attracted ridicule.

Its logo was found to have been plagiarized and its staff were condemned for conducting interviews while masquerading as reporters without informing their subjects they were not. Last February, after the New York Times published an article about how some of the world’s biggest financial institutions were divesting from the oilsands, the war room lashed out on Twitter, questioning the paper’s credibility as a news source, calling its track record “dodgy” and saying it had been accused of anti-Semitism “countless times.” The war room’s director, Tom Olsen, later deleted the tweets and issued an online apology.

The Kenney government also passed Bill 1, which calls for steep penalties against any person or company found to have blocked, damaged or entered any “essential infrastructure.” The list of possible sites includes pipelines, rail lines, highways, oil sites, telecommunications equipment and more. Violators can be fined up to $25,000 and sentenced to six months in jail, or both. Each day they block or damage a site is considered a new offence.

Kenney designed the law to stop protesters affecting any oil industry and pipeline construction. Yet law professors at the University of Calgary argue it clearly violates the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. “Our analysis is that the government would have a difficult time justifying Bill 1 because it is so broad and it does potentially impact marginalized groups more adversely,” law professor Jennifer Koshan told the media. An online petition to withdraw the legislation quickly garnered over 350,000 signatures. A constitutional challenge against the law, launched by the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees, will likely reach the Supreme Court of Canada.

A struggling province

Kenney’s biggest problem is Alberta’s fiscal and employment situation.

Alberta has no sales or payroll tax and imposes low royalties on the energy sector: as a result, the government is projected to earn less money this year from oil and gas ($1.2-billion) than from gaming and liquor sales ($1.3-billion).

Kenney added to his government’s problems by cutting corporate taxes, from 12 to 8 per cent.

As a result, the province is running a $21.3-billion budget deficit, the largest in percentage terms in Canada, while also carrying a nearly $94-billion debt (in the early 2000s, Alberta had no debt and only $8.7 billion by 2013).

Kenney responded by making cuts. One of the first salvos was tearing up the master agreement with doctors and changing their billing codes (health-care accounts for 42 per cent of the government’s operating costs). This was followed by the announcement of up to 11,000 health-care jobs being cut and given to outside contractors. “Basically they are trying to privatize health care,” says Dr. Mukarram Ali Zaidi, a Calgary-based family physician, former UCP activist and outspoken critic of Kenney’s. “Every government would like to come and reduce expenses and expenditure, but there's a proper way of doing it.”

After the pandemic hit, the government announced 25,000 layoffs in the education system, which they said were temporary for the last two months of the school year: some of those layoffs have remained in effect. The government also sought wage cuts and freezes from other public servants. In the university sector, the government imposed severe cuts, which may see tuition fees soar by as much as 21 per cent by 2022.

“You imagine that 30 to 33 percent of our budget will be gone by 2023,” says University of Alberta political scientist Laurie Adkin. “And so it's thrown the universities into crisis: we'll have thousands of layoffs of non-academic staff.”

Kenney also dismantled Notley’s climate change measures and announced the privatization of 175 parks. Initially he scrapped Notley’s limited economic diversification programs, before reviving them.

At the same time, Kenney has been rushing to assist the corporate sector — with debatable results. “So he cut corporate taxes and provided other assistance to oil companies,” says Griffiths, “and many of those oil companies took that assistance, took the tax reductions, took all of that windfall, and they still closed their offices or moved out of Alberta and didn’t create one new job in this province. None of it helped Alberta.”

One of the emerging controversies has been his move to allow four Australian coal mining companies to mine nearly 800 square kilometres of the southern and central Rockies. This will entail massive open pit mines and possibly scraping away mountaintops. It’s also highly water-intensive: Critics say it will not only pollute watersheds that provide drinking and irrigation water for 1.8 million people but destroy tourism and ranching.

On a Friday before a long weekend in May of last year, Kenney’s government quietly scrapped the 1976 Coal Development Policy, which was put in place by former premier Peter Lougheed to prevent open pit mining in that area, as well as safeguard water supplies. Kenney did this with no public consultation, although he did confer with the coal lobby.

This move has alarmed Indigenous groups, landowners and ranchers who graze cattle in the eastern slopes and are now together seeking a judicial review of the decision to dump the coal policy. That case went before the courts last month.

One angry rancher is Gordon Cartwright, owner of the D-Ranch near High River, Alta., whose family has been raising cattle in that area for 120 years. “Here we are going with the same model of encouraging a foreign company to come in and exploit these resources, giving them cheap royalties, tax holidays till they get going,” he says. “(But) that's a short time period of benefit with such lasting damage in terms of liability and consequences. Once you deface those mountains, where you totally changed that landscape, all you're trying to do is mitigate the damage. But you can't turn the clock back in terms of management of native species.”

Today, Kenney’s favourability rating has fallen to less than 40 per cent — the second lowest among Canada’s premiers — down from 61 per cent in the summer of 2019. While he’s not facing the electorate before 2023, some Albertans are beginning to doubt he can recover. And grumblings within the UCP are growing.

When the National Observer asked Kenney’s office for an interview, they declined. We then sent his office a list of questions dealing with the issues raised in this story. Kenney’s press secretary, Jerrica Goodwin, replied, saying: “We reject the premise of your ridiculous, agenda-driven questions. I’m sure you can dig up the government’s previous answers on these questions, as the false allegations you raise have been addressed numerous times in the past.”

“He's an ideologue, he's a true believer in certain convictions that he's just not prepared to compromise on, at least not very readily,” says Kevin Taft. “Jason Kenney comes out of the same kind of firmament as the people who pushed Trump up into his position. He's got real Trumpian tendencies in terms of dividing people, name calling, kind of a distorted populism that plays to ‘us versus them.’ He is very quick to throw insults at people he doesn't agree with… Which culminates in what you see in the U.S. in the last four years — which is division, inequity, anger and largely dysfunctional kind of government.”

This story has been updated to clarify Alberta is projected to make more from liquor and gaming revenue this year than it will from oil and gas royalties

Comments

Mr Bumbles bigly bungles.

Painted himself into a corner, the only chance Alberta has now is to start from scratch, a reset so to speak, which will entail hard choices regarding the oil industry, taxation, and investments.

As a proud former resident of Alberta, it sickens me to see what Mr. Kenney and his party has done to the province. The only surprise is that he is still supported by 40% of the population, which can only be explained by a provincial media that has been bought out or bullied into spewing Kenney's propaganda to gullible believers. It is likely some of that 40% has benefitted by the corruption and wheeling and dealing of the UCP government.

Thank you for this opinion piece. My son lives near Longview, AB, where the proposed coal mine would be. It is all so worrisome. And I know many people are suffering in AB because they've been out of work for so long. This makes them vulnerable to people like Kenney. Kenney should be helping the province transition to a post carbon economy. He is wasting taxpayer's money and gutting social services and environmental protections. It's shameful.

Kenney has a magic touch. Everything he comes into contact with turns to toxic sludge. This from the career politician with sure-fire political instincts. A master of deflection is all that remains. Belligerent, arrogant, incompetent.

However, that may still be good enough for Alberta voters.

*

Anywhere else, Kenney would be a one-term premier. In fact, his caucus would have deposed him by now.

But some 40 of 87 provincial electoral ridings are outside Edmonton and Calgary. 33 seats are predominantly rural. Smaller municipalities account for eight more seats. As long as "conservatives" are "united", rural seats will never flip to the NDP. So the UCP enters into the next election with at least a 35 seat headstart. The finish line for majority government is 44 seats.

*

No matter what Kenney does, I can't see rural and small-town Albertans voting for Rachel Notley.

Moderate voters in rural Alberta may wish for a change of scenery, but for now the UCP remains their only option on the ballot.

Math is difficult, former AB PC leader Jim Prentice famously said. Given the UCP's natural seat advantage, the electoral math looks especially difficult for the NDP.

Bold prediction: Kenney will either retire or be deposed long before the UCP fall to defeat in an election.

An excellent article, long but thorough. One of the best comments inside the article was that Albertan's knew who they were getting....but at the time, seemed to ''want a bully". It's funny how anger can make a person blind to reality....but however red in the face we were...........reality catches up on us eventually.

What to do now, to keep our doctors from leaving for greener pastures, restore the work and benefits of our hospital support workers (those people predominantly of colour who make 17-21 dollars an hour), recoup money thrown at TransCanada, rescue our public pensions from the Fossil fuel besotted grip of AIMCo, get back on programs that encourage green energy, restore a made in Alberta Carbon levy...........etc., etc., is the question.

Because for certain, strip mining the watersheds of water poor provinces, (not only Alberta needs the Saskatchewan Rivers) is the quickest way to guarantee our children don't have a future. If one thing is for certain: Jason Kenney illustrates the dangers of going with ideology over ideas.

Pray God we've had enough of that kind of politics.

That was an astute comment about Alberta's water. Recent research published in the Journal of Glaciology by scientist Ben Pelto (UNBC) estimated that glaciers will disappear from the Columbia River basin in 65 to 80 years. This finding was based on ice-penetrating radar measurements and previous research that found, in part, the melting of BC glaciers occurred at four times the rate in the 20-teens than during the 20-oughts.

The conclusion is that downstream municipal drinking water and agricultural supplies and hydro electricity will be severely impacted. In the case of the Columbia River, that includes southeastern BC and US communities. The Columbia River Treaty would become quite meaningless. Developing huge amounts of zero emission replacement power within two generations is crucial.

The same applies to other watersheds. UBC published a study on glaciers which the CBC picked up in a piece published last August (link below). Some communities like Banff draw their water from deep underground aquifers. But Edmonton and Calgary, together accommodating half the population of Alberta, take their water supplies from the glacier-sourced North Saskatchewan and Bow rivers respectively. Diminish and remove the Rocky Mountain glaciers from their watersheds and the flow will depend mostly on snowmelt and rain -- or a lack thereof. That's a troubling scenario. Drilling deep wells for the urban water supply will succeed or fail on both the quality and quantity of ground water. Given the oil industry's massive activity in Alberta for over a century, one can rightly be curious about the water quality of aquifers near or under Calgary and Edmonton. Agriculture will also be deeply impacted by diminishing flows from glaciers.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/alberta-water-supply-study-1.568…

All this follows research conducted over 10 years ago by Alberta scientist Dr. David Schindler who measured glacier retreat in the Rockies and estimated that flow reduction in glacier-fed Prairie rivers could average about half of current flows by mid-century. Based on that study, Alberta can never say it wasn't warned. Unfortunately, Prairie rivers continue on through Saskatchewan, Manitoba and the NW Territories. Hip bone, knee bone ... you get the picture.

Imagine this great irony: the construction of pipelines through the Prairies to the BC coast, not for oil flowing east-to-west, but for clean water from captured excess coastal rainfall flowing west-to-east. Climate modelling predicts a much wetter coast while the rest of the West sees more drought and record high average temperatures, punctuated by floods and polar vortexes.

I doubt that BC's future political classes will adopt the bullying condescension over its clean piped resource that is currently practiced in Alberta over its filthy top export (that is, until the oil stops flowing sometime in the 2030s or -- too late -- the early 40s), just as Jason Kenney is schlepped off to a private nursing home in Arizona paid for by wealthy social conservative Canadian donors who moved to the Phoenix suburbs years before.

Exports of clean water to the US via a branch line heading south could be built-in to the pipeline plan and used, if needed, to counter any threat issued by Alberta, based on historical precedence of course. Alberta will also be advised by Saskatchewan and Manitoba to not succumb to ideological histrionics because Alberta is only one of several downstream beneficiaries who do not want a temperamental gatekeeper changing the rules mid-stream.

BC can continue its tradition of exercising a calm demeanour during negotiations, but with its hand on the bi-directional valve ready to switch the dial to South from East, though that will obviously violate the constitution if turned all the way, just as Alberta's threat to cut off the oil to BC did. That threat daylighted BC’s unfortunate oil dependency problem. Though BC will likely charge reasonable prices for its water to other provinces, it will have the power to dictate terms and conditions, such as charging a cost plus fee for the electricity to pump the water over the mountains and forcing the activation of serious conservation measures in receiving jurisdictions. It will likely charge more to US consumers.

Jason Kenney does not hold a copyright on bullying others. That trait was at full bore under Ralph Klein, later adopted by Rachel Notley who toned it down slightly. Alberta’s great challenge is learning that electing bullies and condescending leaders from any party doesn’t work to solve their biggest problem: too much dependence on fossil fuels for export and domestically, and not one iota of control over world commodity prices or the changing policy direction of their customers.

Who will remember any of that in the 2040s and beyond as the scientific and economic predictions become reality?

The best time to have added some kind of value added sales tax in Alberta would have probably been in 1948 when BC added their PST. The next best time would have been 1976, when the Heritage Fund was created. The next-next best time would have been any time in and around 1983-87 instead of making huge withdrawals from and then halting contributions to said fund. The next-next-next best time would have been 1989 when the GST was rolled out. And so it goes...

Without a VAT can a province really afford to build infrastructure / provide services without piling on debt and sacrificing its future? Even the federal government, able to print its own money, has a VAT. I'm not an economist, but when the GST was rolled out Canadians were told that taxes on consumers were more efficient than taxes on producers, not sure if that thinking has since changed.

Anyways my point is that maybe it's time for Albertans to starting thinking a bit more like a non-petro province and rethink taxation a bit to give themselves a bit of fiscal breathing room before ballooning debt limits future options. Else Albertans be left with a bust-to-end-all-busts, inestimable environmental clean up costs with hundreds of thousands of abandoned wells, mines and lagoons, dilapidated infrastructure and services, and empty coffers to boot.

A VAT won't remove the risk of that kind of dystopic future for Alberta, but the politics that keeps fiscal options like a VAT from being considered may possibly hasten it.

In all likelihood, Alberta's elected and industry leaders will attempt to goad the federal government to pay for clean up costs, citing all the "largesse" Alberta sent their way through transfers over the boom years. Some very smart people may ask, why didn't Alberta plan ahead? Which, of course, is a very good question.

The problem is that the feds may consider Alberta too big to fail, and bail them out of their continuing failure to account for externalities, like environmental liabilities. Several media commentators have cited cumulative figures somewhere over $600 billion in gross transfers to the feds over the decades, but when you deduct the clean up costs, that will leave probably $100-200B on the positive side of the ledger, a sunk cost to the nation. If Alberta demands the return of some of these prior transfers, then that will require all other provinces and territories who received transfers from the feds to pony up. What is the likelihood of that?

In that light, a PST / VAT can be seen as a commonly practiced stabilizer for the rocky Alberta economy as it is forced to adjust to the 21st Century.

“They think that they can do anything and will always get elected.”

Sadly, for much of recent history, that formula has worked reliably.

It sounds nutty, but Kenney behaves as if he truly believes his fanatical party can weather the storm for two more years and get elected again. There’s only two ways for that to happen—that is, for the UCP’s and Kenney’s personal popularity to rebound in time: one, the market price for diluted bitumen (“dilbit”) itself recovers in a massive, massive rebound and, two, the massive, massive dept Alberta’s piled up since the market started crashing in 2014-15 won’t have to be paid back in a big, ideological hurry; that would seem to require a lot of answered prayers, Kenney for the price rebound, and Alberta citizens that services won’t be cut past the bone.

Since neither of those seem likely (severe austerity budgeting might not happen if the UCP gets turfed in two years but, unfortunately, dilbit market price can’t be set by Albertans, no matter which party they elect), one is forced to consider something even zanier than a wing and a prayer: could it be possible Kenney is intentionally provoking a mass exodus from the province in hopes (or maybe more prayers) whoever’s left will be the most chauvinistic UCPers and dyed in the wool high prairie Redoubters electorally amplified by way of UCP dissenters’ subtraction in self-imposed exile?

That would be crazy, I know—almost half of Alberta voters would have to be driven out of the province no later than six months before the writ is dropped. But, hey, the way things are going, maybe, if Kenney keeps feeding his base its red meat diet and reconciles with some modest-sized faction of—uh—I dunno: undecideds?—gullibles?—and just enough disgruntled doctors, nurses, healthcare officials, teachers emigrate, students, and other job-seekers pack up and scoot—who knows?

But I think he’s wearing a millstone if he’s taking advice from his old boss Stephen Harper: the former CPC leader led a party that was never loved, was assembled by treachery, which won two, back-to-back minorities and a single majority, all by default and a bit of cheating, was turfed as soon as the Liberal members were allowed to vote for a new leader (Ignatieff, recall, was appointed by the party executive, many erstwhile supporters simply abstaining in disgust)—and failed, after almost ten years in power, to get its centrepiece pipeline policy done. In the CPC’s last two years, it watched the courts hand down unfavourable decisions or shit-can CPC legislation, and fine or convict and sentence to jail CPC apparatchiks and an MP for electoral cheating (robocalls, campaign financing offences, &c.), and finally play the bigot card (niqab) to go down in defeat. The CPC was so disliked, and the roster of extremist candidates to replace Harper so embarrassing, Kenney probably reckoned it better not to contest the leadership himself—at least not yet. But he was there, right beside Harper the whole way. Yes, voters do forget, but you can’t say the K-Boy’s tenure in Alberta is in any way anodyne—indeed, at some point, it will be a reminder. That’s the real head scratcher: Kenney’s Ottawa bridge is as good as burned behind him. If not Alberta, he has no other place to go.

So, why, Jason, why?...

An autocrat more interested in power than people peddling easy answers based on big lies? Sound familiar?

If my memory serves Mr. Manning used to argue that extreme ideas were out there whether we acknowledged them or not, and bringing those ideas out in the open so that they could be debated (and softened) would be more unifying. Again, my faulty memory's reconstructed recollection of events in the late 90's, early 00's, and so possibly misremembered/incorrect.. But if I am remembering correctly, then perhaps this might have been premised on a belief that those ideologues might be open to be reasoned with and moderated? Maybe. But could it not also not be 'playing with fire' by providing a platform for folks on the fringes interested only in power, to figure out how to successfully appeal to our blindspots, fears and prejudices? If I remember correctly, some voices at the time warned of this and criticized Mr. Manning for 'playing with fire'. But with 60+ years of relative sanity in western government, Mr. Manning's generation like the rest of us since may have grown up internalizing a quiet confidence that Canada and the US were somehow exceptional in the world, that our democracies were bulletproof and could brush off, ignore, and withstand.

I'm saving a link to this piece because it will be invaluable when election time rolls around. It will serve as a handy reference when we want to remind voters of little-trump's list of scandalous acts. At least up to this time. I'm sure there will be a lot more scandal between now and election time. Please consider updating the list as needed.