Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Greenhouse gas emissions from the aviation sector are flying under the radar.

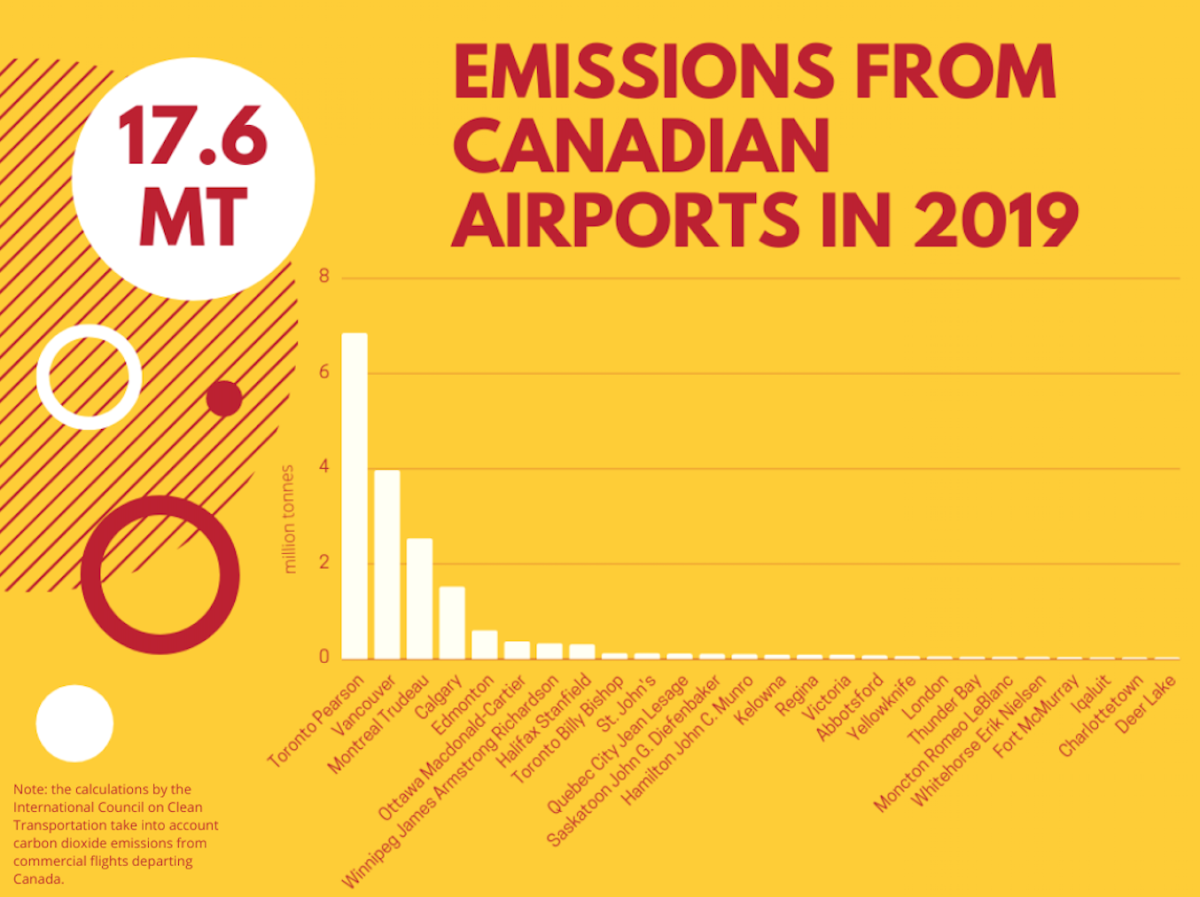

In 2019, carbon dioxide emissions from 26 Canadian airports surpassed 17 million tonnes, collectively placing them high among the country’s top emitters. The airports responsible for the most pollution were Toronto-Pearson, Vancouver and Montreal-Trudeau, respectively.

With 13.3 million tonnes of CO2 recorded in 2019, those three airports represented more than half of the emissions recorded from the 26 airports. To put that in perspective, the country’s top emitter, the Syncrude oilsands operation, spewed about 12.2 million tonnes of greenhouse gases in 2019.

The calculations, compiled for Canada’s National Observer by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), take into account all carbon dioxide emissions from commercial flights departing Canada. The data does not account for other types of greenhouse gases emitted, meaning the figures are likely an undercount.

Traditionally, airports have failed to report all emissions associated with their operations because they exclude emissions from jet fuel burned by international flights leaving the country. Unlike domestic flights, international flights are outside the scope of the Paris Agreement, presenting a crack for emissions reporting to slip through.

Airports record emissions from things like ground vehicles or electricity use. Meanwhile, jet fuel emissions are the responsibility of the airline that owns the aircraft. But because international flight by definition crosses international borders, those emissions are generally kept off national books because no country wants to take responsibility for emissions from somewhere else.

Take Air Canada: its headquarters is in Montreal, but the airline doesn’t exclusively operate in Canada. Emissions for a flight from New York to London would not be reflected in either country’s emissions reporting because the pollution is not happening within the country’s borders.

By including emissions from departing flights in an airport’s total, the data compiled by the ICCT helps put into perspective a fuller scope of the aviation sector’s emissions.

Toronto’s Pearson International was the heaviest-polluting airport and is a clear example of how the full scope of emissions can be hidden. In 2019, it reported just over 66,000 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions to Ottawa. However, when departing fights are added into the equation, the airport’s emissions leap to 6.8 million tonnes. That would rank it as the fifth-largest emitter in the country.

It’s a similar story at other airports. Calgary’s airport authority reported approximately 18,000 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions in 2019, but departing flights were responsible for 1.5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide on top of that.

Comparing emissions from all departing flights in 2019 to the same data from 2013 reveals a growing problem — 2019’s emissions were 32 per cent higher than 2013’s, representing roughly four million more tonnes of carbon dioxide reaching the atmosphere. It’s a trend seen around the world, with the ICCT projecting carbon dioxide emissions to triple globally by 2050 without intervention.

Despite emissions growing across the industry, Suzanne Kearns, a former pilot and founding director of the Waterloo Institute for Sustainable Aeronautics, said airports are well-suited to lead the charge from an environmental perspective.

Unlike aircraft that are always travelling or airlines doing business all over the world, airports are “the sector of aviation that’s fixed in a community” and therefore can be held accountable by communities, Kearns said.

She said the international aviation industry has a collective goal to lower emissions from 2019 levels through a variety of solutions. They include using cleaner fuels, building lighter aircraft to be more fuel-efficient, creating more efficient flight routes and using electric tugs to taxi airplanes from where they land to the gate, recognizing that an engine designed to power a plane travelling at near-Mach speed 30,000 feet in the air is not the most efficient way to taxi on the ground.

“Our challenge is to move into the (climate) space authentically in a way that acknowledges there is harm associated with the air transport sector but equally recognizes ... there's also really strong social impacts,” she said.

“There's a lot of difficulty imposed on society when you can't move around the world,” she added.

Kearns said the flight-shaming movement that encourages people to take more efficient methods of travel instead of flying has forced the industry into a reckoning with its environmental impact, she said.

In addition to cleaner fuels, more efficient aircraft and better flight routes, there should be less flying overall when other alternatives exist if the country is to reduce emissions from the sector.

Ottawa’s forthcoming clean fuel standard, which aims to curb the carbon footprint of different types of fuels, will not apply to jet fuel, Transport Canada confirmed to Canada’s National Observer. However, businesses that provide low-carbon aviation fuels will be eligible to earn credits under the program.

Transport Canada also said it is discussing with the Canadian Airports Council and its members how to update its emission reduction plans for the sector. In 2012, Canada published a plan to reduce emissions from aviation and set a target for annual 1.5 per cent reductions to 2020. The most recent data, from 2018, says there has been a two per cent average reduction.

Comments

Don't want us to take planes? OK, give us back ocean liners. There are plenty of people like me that enjoy going to Europe, Asia, or Australia/New Zealand, and aren't in a hurry to get there.

Unless you plan to sail to foreign countries via sailboat or electric motorboat, the pollution factor is even significantly higher going anywhere by ocean liners than flying. In fact, you should seriously think about curtailing your travel out of your country altogether due to Covid restrictions. We all need to change our ideas of travelling as tourists. You should realize that continuing to do things as we are now without restricting our pollution footprint is spelling a death knell for our children and grandchildren.

"You should seriously think about curtailing your travel out of your country altogether." Not gonna happen: you have to do better than this.