Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Everyone agrees a safe solution is needed for Canada’s current and future radioactive waste. But whether a recently approved disposal facility in Deep River, Ont., is the answer is the subject of hot debate.

The “near-surface disposal facility” (NSDF) will see up to one million cubic metres of radioactive waste buried in a shallow mound at Chalk River Laboratories (CRL), about 190 kilometres northwest of Ottawa. Project proponents argue Canada must find a way to store low-level nuclear waste, some of which is currently not well-managed.

“It's a cleanup project and it needs to be done,” said Deep River Mayor Suzanne D’Eon in an interview with Canada’s National Observer. She called the project a “sensible solution.”

“It's also on a site that is highly secure and highly monitored and expertly monitored,” D’Eon added.

Opponents argue the project, a kilometre from the Ottawa River, poses risks to the drinking water supply for millions, will not safely contain the waste and the company failed to adequately consult many Algonquin Nations. Representatives from six concerned groups recently wrote an open letter to the federal government urging it to halt the project. The waste contains long-lived radionuclides, which many experts say require far more robust containment than this facility will offer.

Radionuclides are unstable, radioactive atoms. Some will remain radioactive for thousands or millions of years, while others are short-lived and decay quickly. The Environmental Protection Agency and other health organizations classify all radionuclides as cancer-causing.

Of the radionuclides present in the waste destined for the NSDF, 19 of 29 listed by Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL) have half-lives of more than a thousand years. This means they’ll be present for more than 10,000 years, said Gordon Edwards, president of the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility, in his 2022 submission to the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC). Another 12 on the list have half-lives of more than 100,000 years, so they will remain in the NSDF for well over a million years, wrote Edwards, a retired professor of mathematics and science with over 45 years serving as a consultant on nuclear issues.

Several groups and many Algonquin Nations are worried about the radionuclides, particularly one called tritium. This radioactive form of hydrogen is a carcinogen most dangerous when ingested because it enters the waterways with ease and can’t be filtered out with water treatment methods either at CRL or at the municipal level, notes Edwards.

These long-lived radionuclides are in “limited” quantities and “intrinsically part of the radiological fingerprints of waste streams at CRL and other CNL sites,” reads CNL’s submission. “It is not practical, technical, or economical to separate the long-lived radionuclides” because much of the waste is in the form of soil and building debris, it says.

CNL is run by a consortium of private companies (including AtkinsRéalis, formerly known as SNC-Lavalin) and contracted by the federal government to operate its laboratories and deal with waste.

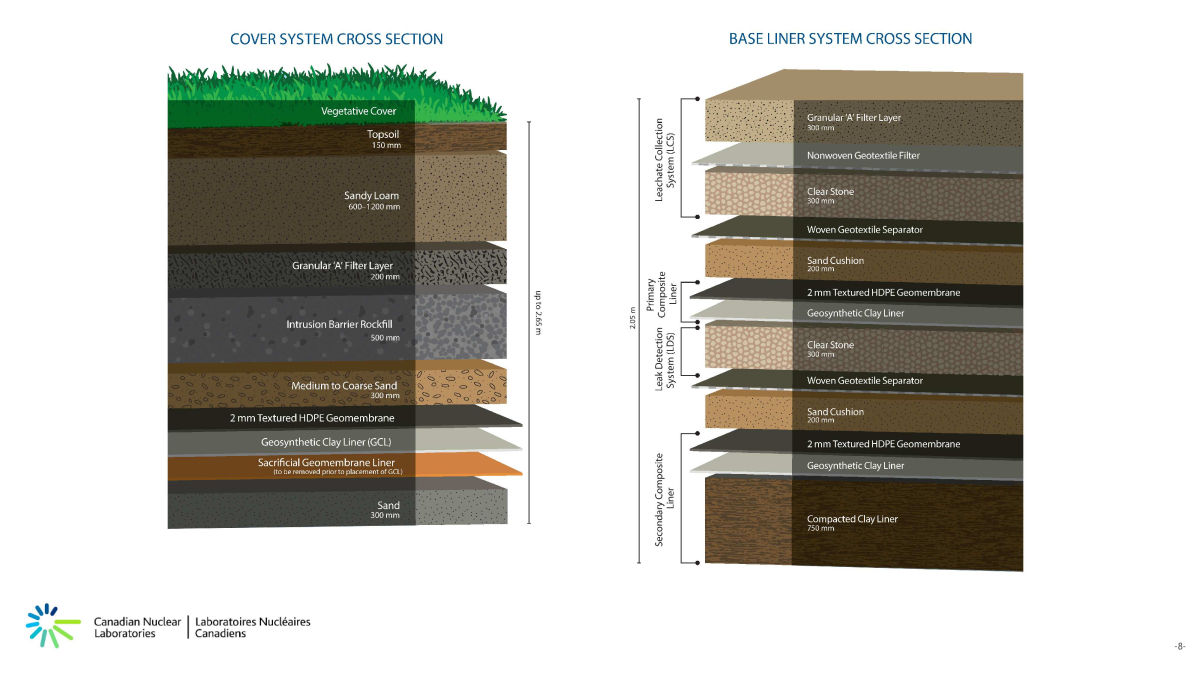

When completed, CNL says the facility will resemble a huge grassy mound the size of 10 soccer fields. The bottom and top of the mound will be lined with synthetic membranes to keep water from getting in, according to CNL.

Construction is expected to take three years and cost $475 million, along with an estimated $275 million in operating costs over 50 years. During that time, CNL will verify all waste placed in the hollowed-out depression in the hillside meets the waste acceptance criteria.

The loose soil and smaller building debris will be compacted into layers and larger debris and waste packaged in drums and containers will be placed in the mound. Water that contacts areas where waste is stored or handled will be routed through a wastewater treatment plant and discharged in nearby Perch Lake. Once all the waste is inside, the final cover of earthen materials and a synthetic membrane go on top to keep precipitation away from the mound.

According to CNL’s draft monitoring plan, wastewater treatment will continue for 30 years and after that, it will be up to the liner and facility design to contain the mound’s contents. Some surveillance will take place to verify the facility is meeting environmental requirements. The top and bottom liners — which are supposed to “remain functional” for 500 years — will eventually erode.

However, it is “a critical flaw” that CNL didn’t plan for waste to be retrieved if something goes wrong later, the Canadian Environmental Law Association argued at the 2022 licensing hearings.

A retrieval plan is important because it gives future generations access to the waste for monitoring, repairs, to move it to a safer location or take advantage of safer technologies in the future, said Tanya Markvart, the law association's environmental consultant.

“We really don't know what's going to happen over the next 100 to 500 or 2,000 years,” said Markvart.

CNL says there’s no plan to retrieve the waste because the facility design will safely manage it long term, but notes nothing is stopping future generations from retrieving its contents. But the law association says it is “unjust to shift the burden” to future generations, who neither created nor benefited from activities that made the radioactive waste.

CNL says the disposal facility is key because some old waste management areas aren’t up to modern standards and “lack robust containment, which has affected the surrounding environment,” reads its submission to the CNSC in January 2022. It pointed to waste management practices from the 1960s where waste was placed in unlined trenches as an example.

These methods are no longer acceptable, and the near-surface disposal facility will accept waste recovered from the environment, legacy waste now in storage (like contaminated protective equipment and mops), as well as future waste. The fact 90 per cent of the waste destined for the facility is already at Chalk River Labs played into CNL’s site decision. Operation costs would be “much higher” on a different site because most of the waste would have to be packaged and transported along public roadways.

The company evaluated other disposal solutions, including intermediate to deep underground repositories in stable rock formations. This type of project provides better containment over the long term, but is typically reserved for intermediate- and high-level waste, said CNL.

CNL said most of the waste — 87 per cent in the form of soil and building debris — does not require these barriers. It was also far more expensive, at more than $6.25 billion compared to the chosen containment mound at $750 million.

CNL also assessed the use of above-ground concrete vaults similar to the L’Aube facility in France but ultimately chose an engineered containment mound because a concrete vault design would cost an estimated $3.4 billion over its lifetime — nearly five times more than a containment mound.

Concrete containment helps keep water out, can be made “durable enough to last for a few hundred years” and provides more of a shield from weathering and erosion compared to a containment mound, according to CNL’s assessment. It would also take up about 1.5 times more land, CNL told Canada’s National Observer in an emailed statement.

Water worries

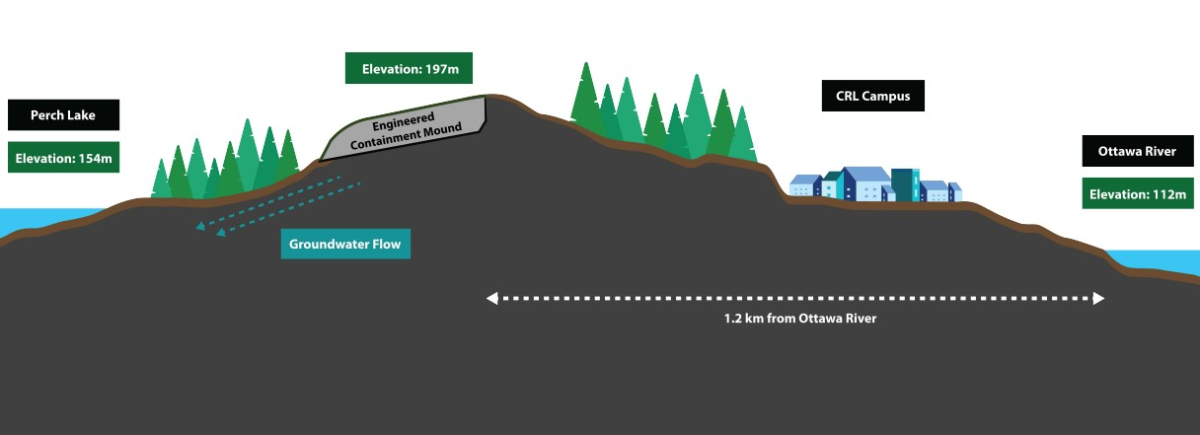

The NSDF’s proximity to the Ottawa River concerns environmentalists, many Algonquin leaders and more than 140 municipalities downstream. CNL materials indicate the facility’s base will be 50 metres above the current water levels of the Ottawa River and on bedrock sloping away from the river.

“Any site anywhere in the Ottawa Valley eventually drains to the river. That's just basic hydrogeology,” said Mayor D’Eon, a member of CNL’s environmental stewardship council, when asked about opponents’ concern for the river.

“So whether you put it on that military base, which some people have said, or five kilometres away, hydrogeology takes everything to the Ottawa River,” she said.

The bedrock slopes towards Perch Lake, which has a creek that feeds directly into the Ottawa River and in the event of an overflow or other design failure, it wouldn’t take long for contaminated water to reach the lake, according to the Ottawa Riverkeeper, a charity focused on the health of the river and its tributaries. Hydrologist Wilf Ruland reviewed the NSDF proposal for Ottawa Riverkeeper and noted the location has “unfavourable geology” and will rely entirely on the NSDF’s engineered features to contain, collect and treat contaminated water leaching from the mound and prevent it from contaminating groundwater and surface water flow systems. The Ottawa Riverkeeper is also concerned about the presence of chemical contaminants and heavy metals, not just radioactivity.

Current tritium levels at Chalk River are far below Canada’s drinking water guidelines and although the new disposal facility will introduce more tritium to a nearby lake and a septic-style area, “we are not expecting to see any discernible difference between what the tritium levels are now,” said George Dolinar, CNL’s environmental protection director, at the 2022 licensing hearing. CNL says the anticipated levels will have no effect on wildlife or humans.

“Based on existing scientific knowledge, there is no such thing as a completely safe level of exposure to carcinogens,” like tritium, reads the submission from Edwards’ organization.

Edwards doesn’t think the waste would cause “a huge kill-off,” after all, “the Ottawa River is huge and the stuff does get diluted,” he told Canada’s National Observer in an interview.

“But we've learned over the years that dilution is not a solution to pollution. It just means that millions of people are going to be exposed to much smaller doses.” When it comes to cancer-causing materials, the number of people exposed “is very important” because when even a small dose of tritium or any other radioactive material is allowed to enter the drinking water for millions of people, the number of expected cancers and genetic mutations is magnified by the size of the population, added Edwards.

Pontiac County, Que., made up of 18 municipalities, is right across the river from the facility. Unlike Deep River, which calls itself the “proud home of Canadian Nuclear Laboratories,” Pontiac has opposed the project location from the get-go, said Jane Toller, head of the county council, in an interview with Canada’s National Observer.

The region has been rocked by floods and extreme rainfall in recent years. Although CNL says it has planned for massive rain events and future impacts of climate change, Toller remains worried. She is familiar with the company’s statements that the facility design, including the cover to keep water away from the mound, are all proven, tested and well-researched.

“But all we can do is hope for the best,” said Toller.

About 300 Pontiac residents work at Chalk River Labs and those jobs are appreciated, “but you have to put that aside,” Toller added.

“I was also invited to a lot of dinners and golf tournaments by the people at Chalk River and I refused,” said Toller. Pontiac County borders the Ottawa River and is downstream of Chalk River Labs, noted Toller. County residents aren’t against permanent storage of radioactive waste, but want it as far from the river as possible, she said.

“In the ’50s, when the dumping was going right into the river, at that time, not much was said. And I think now, this gave people a chance to talk about that,” said Toller. Health in the region is generally poor and that’s also why residents worry about contaminants entering the river, she said. “We are very concerned about our river.”

Toller supports Kitigan Zibi and Kebaowek First Nations, which are currently pressuring the federal government to deny CNL permits required under the Species at Risk Act. Toller says the CNSC’s decision is a “cut-and-dry” violation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which says no hazardous material can be stored on Indigenous land without prior, free and informed consent. While Pikwakanagan First Nation — the Algonquin nation closest to the facility — signed an agreement with CNL, Kitigan Zibi and Kebaowek say they were not adequately consulted and do not consent to the facility.

“I just don't know why our federal government has not paid attention to that,” said Toller.

The CNSC’s recent decision only granted CNL a licence to construct the facility. The company still must apply for an operating licence.

Natasha Bulowski / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

This is the first of two articles about the near-surface disposal facility and the waste it will hold for hundreds of years.

Comments

I'm not going to pretend to know how effective this containment system will be. But something about it, and the attitude of the people behind it, smells wrong to me. The confidence in non-permeable containment layers that seem to be basically big sheets of plastic reminds me of the confident people who changed BC building codes back a few decades ago and gave us the leaky condo fiasco.

First, I do not trust the "expertise" of private sector operators at Chalk River. Nuclear waste storage around the world is either non-existent or sloppy. How can you remediate the dire radioactive effects of molecules that have million year life spans? As long as we keep fiddling about with radioactivity, we only add to the lethal legacy we have dumped on this beleaguered planet.

The various actual "experts" in radioactivity have not, in the tiny slice of time it has been unleashed, come up with any viable solution for cleaning up the mess we have created.. If life on Earth is going to survive it will have to rapidly evolve radiation resistant mechanisms. Evolution may be able to accomplish this, but it is clear that homo stupidus is unlikely to do so.

Exactly. What could possibly go wrong? It's all wrapped in plastic, after all. Plastic with a best before date of now plus 500 years ...

So gee, that should be safe at least till the stuff's half-decayed, in 10,000 years.

So what's to get concerned about ... no one alive now will still be then ... Good grief.

(One has to wonder how many won't be alive because their water, land, and the food grown on the land, are toxic.)