Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Mining the ocean floor for critical minerals was already controversial, but a new groundbreaking scientific study has thrown the industry into chaos as countries negotiate its future.

At a meeting of the United Nations’ International Seabed Authority (ISA) in Jamaica, running from July 15 to Aug 2, countries are negotiating rules to govern deep sea mining. The regulations have been under development for years, but the clock has been running out on an agreement.

But as the negotiations were underway this year, a major study published in Nature Geoscience did more than just expose potential harms to ocean ecosystems due to mining – it revolutionized humans' understanding of how our world works. Mining on the seafloor could affect oxygen levels, and threaten biorich ecosystems in previously unknown ways.

Scientists discovered what they called “dark oxygen.” Until this paper, oxygen was believed to be created solely through photosynthesis, the process by which plants, algae and certain types of bacteria, consume light and produce oxygen. Dark oxygen, by contrast, is created deep in the ocean where sunlight does not reach; in pitch blackness, somehow oxygen was being produced.

For years the scientists dismissed the findings, attributing it to faulty equipment, until finally the conclusion was inescapable. Something was producing oxygen deep below the surface.

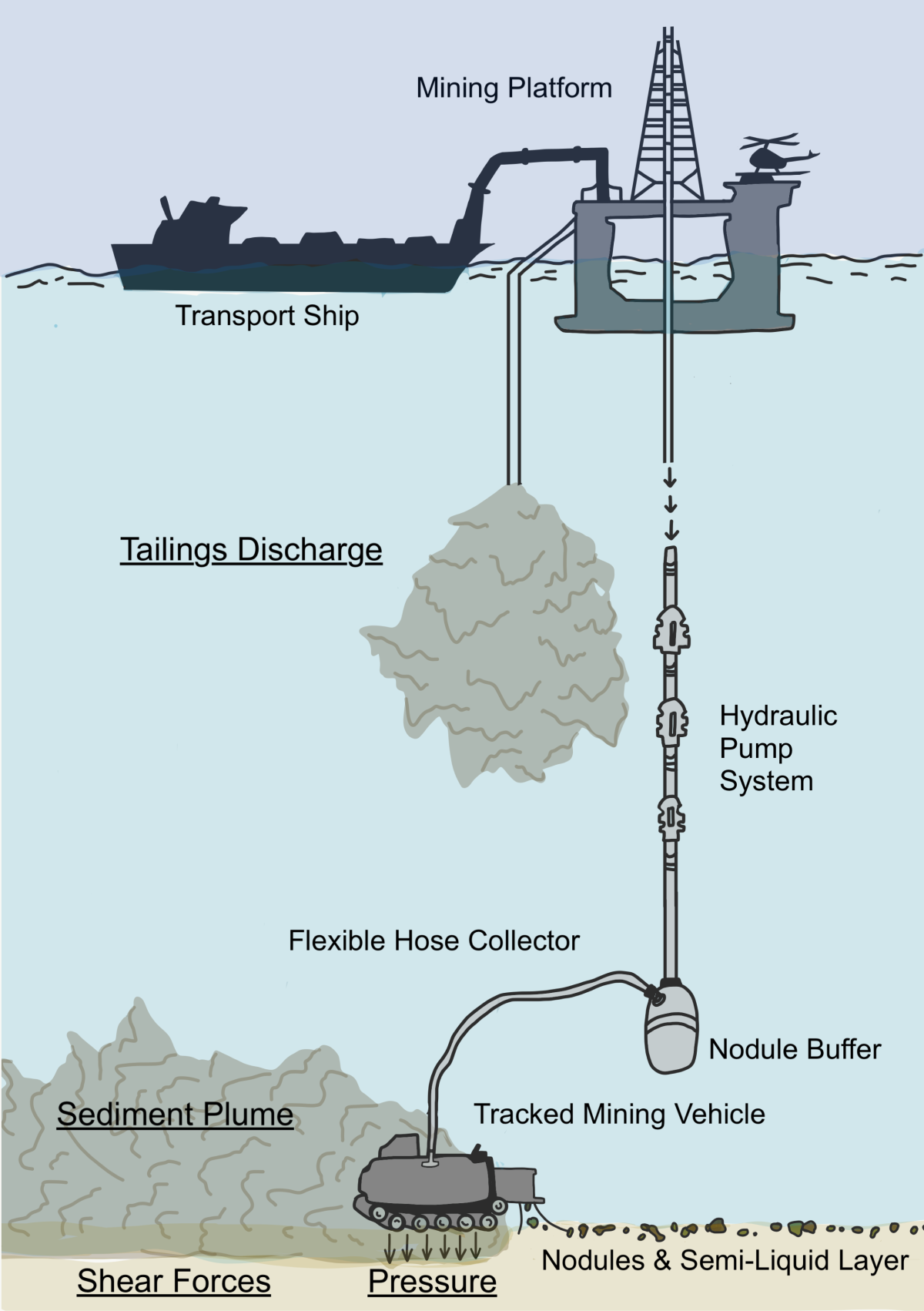

The scientists describe “polymetallic nodules” – lumps of rock containing minerals found around four kilometeres deep that produce a small electric current. That electric current is believed to be splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen in a process called saltwater electrolysis, similar to how hydrogen can be produced using an electric current to split water into oxygen and hydrogen.

The Metals Company wants to mine those nodules and sell them to produce batteries needed for the energy transition. The scientific study that found the nodules produce oxygen was funded in part by the company.

During a press conference Thursday, Greenpeace International’s deep sea mining lead Lousia Casson said the findings — that the very minerals mining companies are after could be producing oxygen in total darkness — has set the debate over the industry’s future alight.

“This is a really revolutionary discovery. It fundamentally changes our understanding of how oxygen is produced on planet Earth,” she said. The findings have “been brought up directly by a number of delegations, from Latin America and Europe inside these negotiations as a clear reason for precaution.”

The discovery could shed light on the origin of life on our planet, according to the paper’s lead author Andrew Sweetman, chair of seafloor ecology and biogeochemistry at the Scottish Association for Marine Science.

“To power the green economy we need to extract metals from the ground or potentially the deep ocean,” Sweetman also said. “So what we have discovered means that we’re going to have to carefully think about if deep ocean mining goes ahead, where that mining should take place.”

The Metals Company strongly disagrees with the findings. In a statement, it said the findings are “questionable” due to a “flawed methodology” and the results are “likely compromised.” It also took issue with the findings being published in Nature Geoscience, which the company accused of having a negative deep-sea mining bias. Nature Geoscience is a peer reviewed journal, published by Nature, which is among the world’s foremost scientific journals. Published since 1869, it was the journal that revealed the structure of DNA, the existence of the neutron, the existence of plate tectonics, and the structure of the human genome, among many other foundational discoveries.

“Our team is preparing a comprehensive rebuttal to contribute to the scientific literature and ensure accurate information is available,” the company said.

According to a powerpoint presentation seen by Canada’s National Observer, delivered at a side event during the negotiations, The Metals Company dedicated several slides to casting doubt on the “dark oxygen” hypothesis. The slides note the lead scientist, Andrew Sweetman was contracted to conduct scientific research for the company, and says the University of Southern Denmark has been unable to replicate the findings. The company’s planned rebuttal will use the University of Southern Denmark’s findings, according to the powerpoint.

Casson said it is notable how strongly the company is trying to discredit the findings.

The Metals Company has “really tried to position themselves as aligned with science, despite hundreds of scientists calling for a pause on deep sea mining, and I think this perhaps reveals just how significant this discovery is [for] potentially impacting on their operations,” Casson said.

In an undated open-letter signed by more than 800 marine scientists from over 40 countries, the scientists wrote that the deep sea is home to a large proportion of the planet’s biodiversity, and plays a crucial role regulating the climate.

“[D]eep-sea ecosystems are currently under stress from a number of anthropogenic stressors including climate change, bottom trawling and pollution,” the letter reads. “Deep-sea mining would add to these stressors, resulting in the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning that would be irreversible on multi-generational timescales.”

Emma Wilson, a policy officer with the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, said The Metals Company is wielding massive influence over the ongoing negotiations. The entire reason countries are “in this crazy accelerated race towards adopting a mining code as soon as possible,” is because of the company’s push to mine with Nauru’s backing.

Countries were given a two-year deadline to reach an agreement when the small Pacific island state Nauru notified the ISA of plans from Nauru Ocean Resources (a subsidiary of Vancouver-headquartered The Metals Company) to begin deep sea mining in 2021. The two-year-rule provides for mining plans to be approved after two years — under whatever rules exist at the time. Given the controversial nature of deep sea mining, the race to land binding rules began in earnest when Nauru announced its plans.

When the two-year mark passed last summer, The Metals Company announced it would file an application for commercial mining in 2024, regardless of what progress had been made on the rules.

“So we do have this really odd situation where the member states of the ISA are essentially being held hostage by this one company, and being pushed toward that outcome that the company is so desperately seeking, mainly in order to keep their investors on board,” she said.

In September 2021, just months after it announced its intention to file a mining application, The Metals Company was listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange to raise funds. To keep investors on board, the company needs to show progress which is one reason the company is fighting the scientific findings, environmentalists say.

Wilson says despite the company’s pressure, countries are pushing back — including by deciding not to have a third meeting this year, “which is a big signal that states are starting to say ‘Well no, we're done bowing down to industry pressure, and we're going to take this at our own pace’,” she said.

At the ISA negotiations, countries that had previously expressed interest in deep sea mining are beginning to shift, and now are supportive of banning, or at least introducing a moratorium, on the industry until its environmental impacts are better understood.

“Just this week… we've seen five new states coming out and supporting a precautionary pause or moratorium,” she said, referring to Tuvalu, Honduras, Guatemala, Malta and Austria.

That brings the total countries against deep sea mining to 32. Canada’s official position is that it supports a moratorium.

“We recognize the importance of marine ecosystems as a climate regulator, and will continue to take and advocate for a precautionary approach to development — an approach that aligns with efforts to combat climate change and pollution, and to protect biodiversity and habitats,” Global Affairs Canada said in a statement last year.

“This is why, in the absence of both a comprehensive understanding of seabed mining’s environmental impacts and a robust regulatory regime, Canada supports a moratorium on commercial seabed mining in areas beyond national jurisdiction.”

Matthew Gianni, founder of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, said The Metals Company is exploiting loopholes to serve its agenda. Because the mining occurs far out at sea, it would be governed under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. That law essentially requires that activities be sponsored by a country, which is then made responsible for ensuring rules are followed.

“The Metals Company knows that Nauru is going to be far less capable of doing that than the Canadian government would be,” he said, adding that the cost to build a relationship with a developing country like Nauru would be far cheaper than building that relationship with a country like Canada. “A little bit of money goes a long way.”

This story has been updated to clarify the relationship between the peer reviewed journals of Nature Geoscience and Nature.

Comments

The environmental degradation of the mining industry continues unabated on the earth's surface and they now wish to take their dangerous practices out of sight under the oceans and affect the oxygen production discovered down there, a hard NO on that nonsense.

Totally agree, the industry is just focused on profits, with total disregard to the environment impacts to the ecosystem. As usual, governments are foot dragging and gambling on the future of this planet by ignoring the evidence.

Humanity just keeps finding more was to destroy the life support system nature built for us.

In an article by George Monbiot in the Guardian this morning, he talks about "the planet as periphery."

That's the blinkered, egoistic attitude of men in a lather about making their fortune, especially with something "new;" it's also clearly an altered state, a mania even, that has to be treated accordingly. So despite being the wellspring of a capitalist system that has built so much, the checks and balances have never been more needed.

Enter the scientific journal "Nature" with its peerless reputation providing scientific consensus on a par with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Kind of amusing that they sponsored some research, hate what it found out, and now have to desperately repudiate it.

The same thing happened before with the tobacco companies, the oil and gas industry, the chemical industry. governments regulating (or not) toxic products, and the list goes on and on....

I don't think we know what this means. How much life does that oxygen support? How dependent is that life?

Here's a final metric we actually do know. They did a mining operation on a test area some 20 years back, and came back to find what happened to the life down there. The micro-life was back to about normal some species down 20%, but the larger creatures were 40% less population.

That's not great, but it's not devastation, either.

Whether we even NEED this mining source is still very much a debate. All those articles about us having to rape the Earth to get EV metals were way over the top - Alberta found a million tonnes of lithium in brines that will need no mining at all the same month. India found six million. And all the EV metals are about 95% recyclable.

It may remain like fusion - this "cool idea" that's always 20 years away.