Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

As the globe’s “do or die” UN climate conference gets underway next week, Canada must scale up efforts to meet its ambitious ocean conservation targets to simultaneously prevent the wholesale collapse of marine biodiversity and tackle climate change, experts say.

As the largest ecosystem on Earth, the ocean is critical to regulating the climate and helping produce oxygen, rain, drinking water, and food, as well as sustaining livelihoods for three billion people.

An invaluable asset for mitigating the climate crisis, the ocean absorbs about 30 per cent of the carbon dioxide produced by humans while weathering an increasing number of marine heat waves, ocean acidification, oxygen and biodiversity loss, and pollution and plastics.

“There’s a growing understanding the biodiversity and climate crises are interlinked, and that we need to address both of them together,” said Alex Barron of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS).

“And marine protected areas (MPAs) are the most effective tools to do that, but they need to be well-managed and strongly protected.”

Approximately eight per cent of the globe’s oceans are protected by MPAs. As he heads to COP26, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has committed to the 30x30 pledge — to protect 30 per cent of Canada’s land and oceans by 2030 — and he is urging other world leaders to follow suit.

Yet due to a lack of standardized minimum protections, many of Canada’s existing MPAs are vulnerable to a range of potential threats, like deep seabed mining, oil and gas exploration, destructive bottom trawling fisheries, and dumping, Barron said.

“You know it’s like that little hairline crack in your windshield,” she said. “Everything should be fine, but if something hits it … it could all smash into a thousand pieces.”

Canada’s 30x30 pledge is commendable and absolutely necessary to curb global warming and recover ocean species and habitat, said Barron, but there’s the danger that a rush to quantity may compromise quality when it comes to MPAs.

In 2019, Canada announced it had protected 14 per cent of its oceans.

Yet after analyzing 18 of the best-protected MPAs — a little more than half the area Canada counts towards its ocean conservation targets — CPAWs found most are weakly protected, Barron said.

The MPAs studied cover 8.3 per cent of Canada’s oceans, but only 0.4 per cent of the total area is strongly protected by federal MPAs, while nearly six per cent is weakly protected, and 0.3 per cent are incompatible with a conservation designation, the CPAWs MPA Monitor report showed.

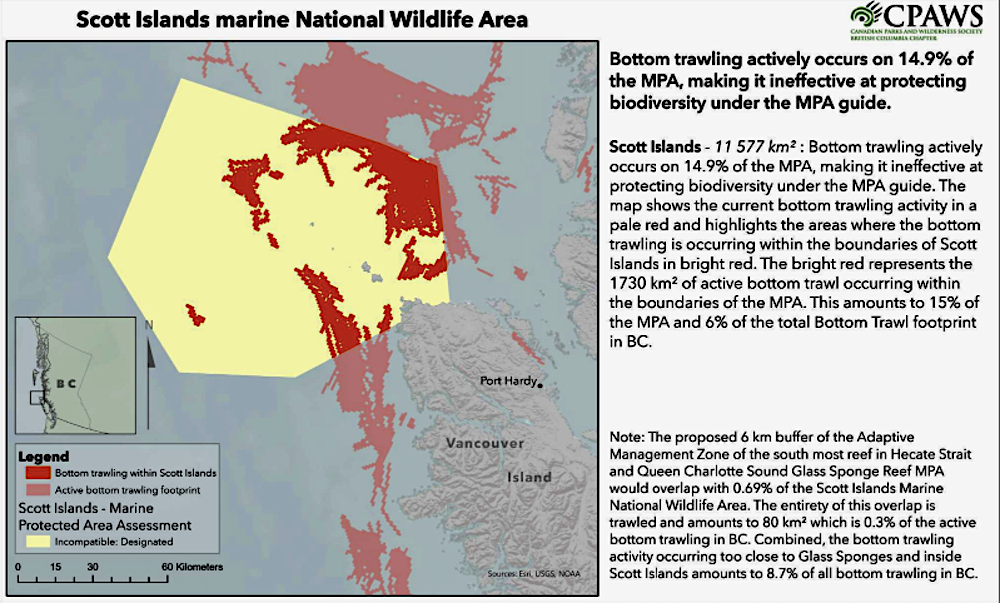

The results were driven by two very large and weakly protected MPAs, the Scott Islands marine National Wildlife Area in B.C., and the Tuvaijuittuq interim MPA in the Arctic.

"We found that most Atlantic MPAs were strongly protected, Arctic MPAs tend to have weaker protection but fewer activities occurring, and B.C. was a mixed bag," said Barron.

As Nunavut’s massive proposed Tallurutiup Imanga marine conservation area — covering almost two per cent of Canada’s ocean — hasn’t been fully formalized, the MPA’s vulnerability was not assessed, she added.

Concerns over Canada’s ocean protection measures are long-standing among marine conservation groups, Barron said.

In 2019, the federal government committed to applying minimum standards that ban bottom trawling, oil and gas, mining, and dumping to any new MPAs.

But that commitment doesn’t immediately apply to already existing protected areas, Barron said, and MPAs with existing oil and gas licences or the ability to bottom trawl are still being counted towards Canada’s marine conservation target.

The federal government has said existing MPA protections will be revisited and stakeholders consulted as management plans come up for review, typically every five years, she said.

If during the review process, fossil fuel or mining companies don’t relinquish exploration licences or permits, the area within the MPA overlapping with licences would no longer be counted towards federal marine conservation targets, according to Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

But oil and gas, mining, trawling, and dumping activities are incompatible with MPAs and compromise conservation goals since the activities have far-reaching impacts on marine ecosystems, Barron said.

Any MPAs that allow the activities should be wholly discounted when meeting federal marine protection targets, according to the CPAWS report.

While the threats from oil and gas activities in MPAs are currently limited due to a long-standing moratorium on offshore oil and gas drilling in B.C. and a more recent one in the Arctic, they can be revoked if not legislated, Barron said.

“It does provide protection now, but we saw what happened in the U.S. when one person comes into power and decides to change everything,” she said.

“That's the risk right now. It's just not permanent.”

Currently, two Canadian MPAs are incompatible with biodiversity conservation, another eight are weakly protected, and seven are strongly protected, according to CPAWs analysis conducted with the MPA Guide — a scientific, standardized tool to evaluate and compare the levels of protection in marine conserved areas.

If Canada actually implemented the promised minimum standards in all its MPAs, it would go a long way to address the existing patchwork of conservation gaps and weaknesses, Barron said.

“The problem is we just don’t have those clear minimum protection standards and a number of activities can occur from site to site, and each is unique,” she said.

“So they all have different threats and risks.”

Rochelle Baker / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer

Comments

It may have been in this very publication that I read about a "Marine Protected Area" off the East Coast of Canada, and a sea-bed oil drilling operation that was approved a very, very short distance from its boundaries well after it had been designated.

I was dismayed, but then I have the same reaction to timber-harvesting and mining in National Parks. The entire original purpose to preserve them in their natural state, and the same for Provincial Parks.

Frankly, if we were really serious about saving crucial ecosystems, all coastal corridors should be protected, and really protected, both land and earth, as coastal marine life dies without nutritients carried by rivers and creeks from the forests.

North American Governments' idea of "protection" at this point seems to be funding "cleanups" after the damage is done.

They need a vocabulary review. Using a dictionary instead of carbon producing industry promotional material might help.