Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

It may take more than 2,800 years to clean up some of the decommissioned oil and gas wells currently dotting Alberta’s landscape, a senior regulatory official warned in a recent presentation made privately to the industry.

That means the burden of returning the land to a natural state — called reclamation — could fall on the next 93 generations. The Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) official outlined the situation in a September 2018 presentation to oil and gas professionals as he made the case for stronger regulations.

While industry and government officials have long touted Alberta’s oversight as world-class and ahead of other jurisdictions, Rob Wadsworth, vice-president of closure and liability for the AER warned in the presentation that the province’s oilpatch was facing a financial and ecological catastrophe due to weak regulations.

It’s unlikely that well-owning companies will be around to clean up the mess in a few hundred years, said Blake Shaffer, a post-doctoral fellow at Stanford University who has studied well liabilities in Alberta.

“This is a big issue, and we need some policy changes,” said Shaffer, who is also a C.D. Howe Institute fellow and economist at the University of Calgary. “These shouldn’t be things that are multi-generational.”

National Observer obtained the presentation through a freedom-of-information request as part of a joint investigation with Star Calgary.

It doesn’t say how many wells would remain on the landscape for thousands of years, nor does it name the companies because “ the presentation may no longer represent the current state,” an AER spokesperson said in a May 21 email responding to questions from National Observer and the Star.

Alberta has an estimated 343,000 wells in total, according to the provincial government. Wadsworth’s presentation focused on the “top 15” companies with the biggest inventory of decommissioned wells. These are classified as abandoned, meaning they’ve been plugged, but the land hasn’t been returned to a natural state.

Wadsworth blamed the problem on the regulator’s “insufficient” collection of security deposits on wells and an increasing number of companies with “questionable” ability to pay for cleanup. Unlike most oil and gas producing jurisdictions, Alberta also doesn’t impose cleanup deadlines on oil and gas companies.

It leaves a multibillion dollar liability that is much larger than the regulator’s publicly stated figure of $58.65 billion to clean up oil and gas wells, potentially leaving taxpayers to foot the bill.

However, the cost of cleaning up oil and gas wells in Alberta varies, depending on the source.

'It’s so obviously not a sustainable well-liability regime'

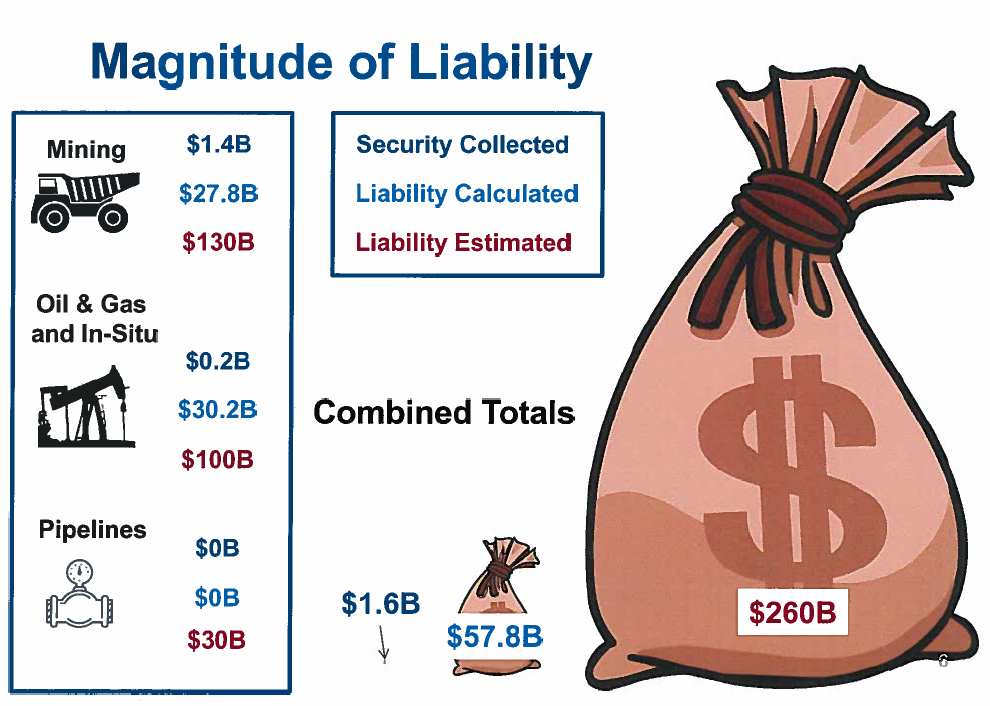

The presentation repeats a staggering estimate that it could cost $260 billion to clean up what remains of Alberta’s oilpatch, which the AER said was based on “a hypothetical, worst-case scenario” where “industry stopped producing all hydrocarbons.” It says the liabilities include $130 billion for mining — most of which involves waste reservoirs in the oilsands, called tailings ponds — $100 billion for conventional oil and gas and $30 billion for provincially regulated pipelines.

The estimate was first reported by National Observer, Global News and The Star last November, based on a February 2018 presentation also given by Wadsworth, which said the numbers were a “rough estimate” that was likely to grow.

At the time, the AER said the $260 billion figure had “not been validated by the AER” and using it was an “error in judgment,” statements it reiterated this year.

So far, the province has collected about $1.6 billion in liability security from oil and gas companies, with about $200 million of that allocated for well cleanup.

There are similar liabilities mounting in other jurisdictions such as Saskatchewan and B.C., but B.C.'s NDP government announced a new regulation on May 31, that would impose legal timelines for companies to restore old oil and gas sites. The provincial government is also phasing in a new levy, over three years, that will be collected to cover the liability costs of cleaning up orphan sites.

The cleanup timelines in the AER presentation are based on the companies’ current rates of abandoning and reclaiming their wells. The industry averages are based on operators with a history of decommissioned wells and an inventory of inactive sites, the AER said in its response to questions about Wadsworth’s presentation.

“The estimates included in the presentation reflect a snapshot in time that was based on an unlikely worst-case hypothetical scenario,” said the statement from the regulator’s spokesperson. “Development and closure activities occur constantly, therefore estimates related to the cost and time associated with liability are always in flux.”

The office of Alberta Energy Minister Sonya Savage and the province’s Ministry of Energy did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. The opposition NDP said no one was available to speak and declined an interview, as did the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, the industry lobby group.

Slumping companies are leaving millions of dollars in unpaid property taxes as they struggle to pay their bills. Rural municipalities in Alberta revealed in a recent survey that they are facing $81 million in unpaid property tax bills from oil and gas companies that are going bankrupt or refusing to pay.

On April 30, a Calgary-based natural-gas company called Trident Exploration shut down, unable to cover the cost of mounting liabilities and unpaid property taxes. The closure could double Alberta’s inventory of more than 3,000 orphan wells, which are sites with no legal owner to pay for their cleanup. Trident leaves behind 4,700 wells and a cleanup bill of $329 million.

Meanwhile, a report by online news outlet The Narwhal revealed the provincial regulator wants to speed up approvals of drill licences, a move that oilpatch industry lobbyists say could reduce current average wait times of five days to 15 minutes, according to internal records released through Freedom-of-Information legislation.

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers told The Narwhal that it saw the changes as a “significant opportunity” to make approvals more predictable while maintaining adequate environmental oversight and making it easier for companies to make a profit.

The estimated cleanup timelines in Wadsworth’s presentation don’t include orphan wells. In Alberta, such sites are handled by the industry-funded Orphan Well Association, which Wadsworth’s presentation described as “increasingly overloaded.” The Alberta government gave the association a $235-million loan in December 2017 to accelerate the cleanup process.

In the presentation, Wadsworth said Alberta’s conventional oil and gas basin is “mature” — meaning production has passed its peak and is beginning to decline. He also lists the price of Canadian oil and gas and competitiveness with the United States as “accelerating factors” in Alberta’s liability woes.

The province’s system of collecting money to cover well cleanup costs is “only designed to work when things are booming,” and overestimates the value of companies’ assets, said Lucija Muehlenbachs, an economist at the University of Calgary who studies oilpatch liabilities. In most cases, the province doesn’t collect any upfront security on wells, allowing companies to put off cleanup until they have no money left to pay for it.

“It’s so obviously not a sustainable well-liability regime,” Muehlenbachs said.

The average time needed to reclaim all decommissioned wells is 198 years, the presentation said. Even the “best” company out of the 15 that have the largest backlogs of decommissioned wells would need 51 years. The “worst” company would need 2,830.

“We’re almost getting into geological times,” said Thomas Schneider, an accounting professor at Ryerson University who has tracked liability management issues in the oilpatch for years.

“Alberta was a have-not province (a) long time ago. It could very well be again in the not-too-far distant future and could have a lot of contaminated areas as a legacy of its oil and gas history.”

What's the cost?

The estimates come at a tricky time for new Alberta Premier Jason Kenney, who was elected on promises to advocate for the province’s energy sector and go after environmental charities who have questioned the industry’s ethics and environmental impact.

The AER said it is working with the Alberta government to ensure industry—not taxpayers — handles the costs of and responsibility for cleanups.

It’s now common for companies to take 50 years to reclaim wells, said Daryl Bennett, director of Action Surface Rights, a group that advocates for landowners who have wells on their property. “Their business model is pump and dump and avoid it for as long as possible.”

Though many companies operate responsibly, a few know they can avoid their cleanup responsibilities by delaying as long as possible because Alberta doesn’t impose deadlines on reclaiming inactive wells, Bennett said. It’s especially harmful since many operators are behind on their lease payments to landowners, and their property taxes.

The problems are compounded by a spike in companies going bankrupt since oil prices tanked in 2015, Wadsworth’s presentation said.

Between 2010 and 2014, when oil prices were between $70 and $100 a barrel, the AER recorded only a handful of insolvencies per year, the presentation said. But between 2015 and 2017, after prices fell to between $40 to $50 per barrel, insolvencies skyrocketed, with 56 companies going under in just three years.

The money that’s likely to come out of oil and gas production in Alberta in the future probably won’t be enough to cover cleanup costs, said Schneider. But it’s also difficult to try and collect the money now when the industry is already under significant strain.

“How do you take billions of dollars (in cleanup costs) out of industry when they’re struggling?” said Schneider. “It’s a tough one.”

Wadsworth’s presentation shows the AER was continuing to repeat the $260-billion cleanup figure up to six weeks before the joint investigation first published them.

“The way we calculate liability is evolving,” the regulator said in its statement. The AER also noted that it expects to improve its estimates through a program that encourages companies to work together to reclaim oil and gas infrastructure.

In a separate Freedom of Information request, The Star also obtained data used by the AER to calculate the $260-billion estimate. It included six detailed spreadsheets used by AER experts to calculate the oil and gas portion of the $260-billion figure, including average cost estimates from three consultants.

The AER calculated the mining figure based on the average rate for cleaning up tailings ponds, and used estimates from the National Energy Board, Canada’s federal pipeline regulator, to arrive at a cleanup cost for pipelines within Alberta, the documents said.

Shaffer believes it could actually be faster and cheaper to clean up the oilpatch than the estimates in Wadsworth’s presentation. If a lot of companies failed at once, wages would likely plummet and drive labour costs down, possibly speeding up parts of the process.

Regardless, he added, these are still enormous numbers. “The bigger issue at this point is recognizing that there is this sort of looming problem in Alberta and our policy is not well designed to deal with it.”

The regulator aims to tighten its rules

In the September 2018 presentation, Wadsworth outlined the regulator’s plan to tackle the situation.

The AER has tightened scrutiny on the companies operating in the province. It’s also calculating liability costs across the entire energy sector and revising the system it uses to assess whether companies can pay for their environmental obligations.

The Office of Alberta’s Auditor General, which holds government agencies accountable through audits, is also working on an audit of the management of orphan oil and gas sites, the regulator said.

The AER also said it’s analyzing the impact of a Supreme Court decision that requires energy companies to fund the cleanup of their old oil and gas sites before paying off other debts.

The previous NDP government had promised to impose clean up deadlines on oil and gas sites, but newly-elected United Conservative Party Premier Jason Kenney said he would encourage the federal government to give companies financial support for environmental reclamation instead.

Muehlenbachs hopes the contents of Wadsworth’s presentation — and Trident Exploration’s recent bankruptcy — will motivate the provincial government to tighten the law and prevent oil and gas liabilities from becoming a long-term public problem.

“They pushed regulation down the road,” she said. “Maybe this is enough to change the system now rather than later.”

Comments

If they want a pipeline, maybe they should pay their liabilities first. This is how humans live. We guarantee a pipeline will be built in 2,800 years!

What a ridiculous statement. We can not accurately guess the price of the worlds energy commodities in 5 years much less what the province of Alberta will do with oil patch sites for 2800 years.

Who's writing the garbage Van. If anything is fake, it's you. This comment was simply a clever referral to fossil fuels and dinosaurs. National Observer is one of the finest online publications. Independent Publisher of the Year! Get used to it, it's the future!

This is not fake Geoff Smith are you a landowner with pipelines, satellites facilities, well leases, active, discontinued, abandoned? Until you do then you have no clue about what is happening in rural Alberta. I have a pipeline in a discontinued state for over 10 years, the company will never reclaim it. Yet I gave contamination on my property. This is a well known company just made $900 million in its first quarter 2019. AER only holds a minimum of AER hearings mine was last week. All about aging infrastructure and the time to reclaim the soil for a reclamation certificate and so I wait for the decision to come in 60-90 days. My file took 1.5 years to be granted a hearing ...talk about Red Tape to protect my property Rights.....

Hi Wouter, thanks for providing your feedback. Did you read the entire story, beyond the headline? It was sourced and based on facts and evidence, related to the actual pace of cleanup on sites. This information was provided by the regulator itself in a discussion that it had with industry. The statement came from the regulator which reports to the Alberta government. What part of this do you thin is ridiculous?

There won't be any energy commodities in 2,800 years, don't worry about it. That, or no people.

North Dakota requires drillers to put up a bond for the cost of decommissioning each well. It is not enough but is more than what Alberta does. Farmers by law have to allow companies to drill on their land. However before you can go back to growing something on it, it has to be re-claimed. Just like when a gas station shuts down or a house has an underground oil tank that leaks. According to CD Howe to reclaim the 115,000 orphan oil and gas wells would cost $9billion.

All you high and mighty virtue signaling folks bad-mouthing the oil sands should also recommend that the feds return all the equalization payments AB has ever made to Canada to help with your so-called 2800 years of clean-up. Just saying.

does that include the 50 years when Alberta received equalization as a have not province before the oil rush.

And of you use any fossil fuels or byproducts you are a hypocrite

By the same line of "reasoning", your continued use of clean air and water makes you a hypocrite. Please grow up and take this crisis seriously.

What ever the right numbers are concerning the environmental mess being left behind from the O&G industry the fact is they are leaving it for future generations to clean up. Not to mention the harm being done to our health. These are fo the most part mulitinational corporations getting away with murder all the while taking huge profits for themselves. All under the nose of our political leaders. Time they were called out and made to pay.

Far too accurate a description. The profiteers know to take the money and run, as the public will never catch up to them.

Understatement of the millennia:

"Alberta could have a lot of contaminated areas as a legacy of its oil and gas history."

Pity the next few generations of Alberta's children, given that "Jason Kenney said he would encourage the federal government to give companies financial support for environmental reclamation instead." — in other words, let's have ALL Canadian taxpayers pay for AB's lack of integrity and responsibility for years of environmental degradation. Let's watch what happens to the Athabaska River and delta — has legislation been approved to allow tailings to flow into that invaluable ecosystem?

Why shouldn't the federal government pay part of the cost they have received many many billions in profits from the oil and gas sector and for those that don't know B.C. also has a large mess to clean up themselves.

Provincial government.

Why shouldn't the federal government pay part of the cost they have received many many billions in profits from the oil and gas sector and for those that don't know B.C. also has a large mess to clean up themselves.

Understatement of the millennia:

"Alberta could have a lot of contaminated areas as a legacy of its oil and gas history."

Pity the next few generations of Alberta's children, given that "Jason Kenney said he would encourage the federal government to give companies financial support for environmental reclamation instead." — in other words, let's have ALL Canadian taxpayers pay for AB's lack of integrity and responsibility for years of environmental degradation. Let's watch what happens to the Athabaska River and delta — has legislation been approved to allow tailings to flow into that invaluable ecosystem?

How do they come up with a number like 2800 years?

Hi Greg, the number was calculated based on the existing pace of abandonment/reclamation.

Very well put.

Oil and gas companies are recklessly polluting our atmosphere, denying the impact. Why should we expect them to behave any differently when it comes to polluting our soil and water. The article sums it up perfectly in one line “Their business model is pump and dump and avoid it for as long as possible.”.

The need for strong regulation and adequate cleanup payments on an ongoing basis is obvious. Politicians focus on being elected / re-elected, has led to immoral behaviour on the part of industry and politicians which is destroying the Alberta landscape, and our futures.

2800 years effectively means "never" under the current plan, but still perhaps amounts to "too much red tape" for those preferring slogans and ideology over evidence.

I'm no expert, but I strongly suspect that the longer this effort is put off the more expensive it will be become. As the saying goes, "rust never sleeps".