CO2 from jet fuel is soaring 4 times faster: what can save the day?

The global aviation industry has started burning jet fuel like there is no tomorrow. Its climate pollution is rocketing upward. And hoped-for "solutions" like biofuels and electric planes are being buried by the rising flood of emissions. In response, a growing number of climate-concerned people, including the world's most famous climate champion, Greta Thunberg, are advocating less flying.

If you're interested in an illustrated guide to the hot topic of soaring flight pollution and what's being done about it, you're in luck. I've read dozens of detailed reports, built the geeky spreadsheets and created a series of charts that tell the story.

CO2 taking off

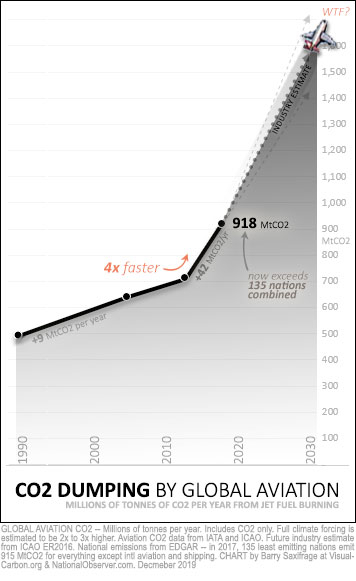

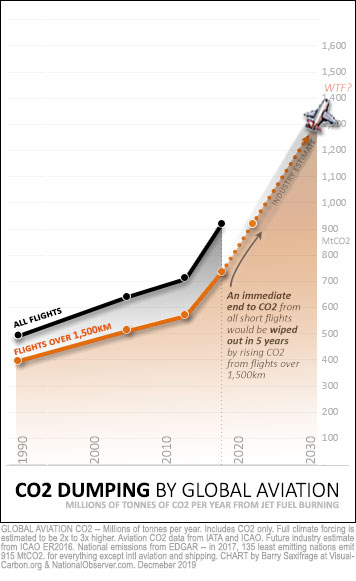

Let's start by looking at the dramatic rise in climate pollution from global aviation. My first chart shows past and projected CO2 data from the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Air Transport Association (IATA).

As you can see, the aviation industry's climate pollution is taking off. Its CO2 is now rising four times faster than its already scorching pace in previous decades.

The burning of jet fuel is increasing by an additional 44 million litres every day — an additional 16,000 million extra litres each year. That's like burning 1,000 tanker trucks more than the day before. And then 1,000 more than that the next day … ad nauseum.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) credits the "spectacular expansion" of jet fuel burning, along with increasing plastic production, for fuelling the vigorous rise in global oil demand.

At current rates, the aviation industry will soon be dumping a billion tonnes of CO2 per year into our atmosphere. That exceeds the combined emissions of 135 nations … for everything.

As the soaring dotted line on the chart shows, the industry isn't planning to stop at a billion tonnes. They are spending trillions of dollars to buy more jetliners, expand airports and build the fossil fuel infrastructure that will push their climate pollution to ever more dizzying heights.

And that’s just the portion of their climate pollution the industry is willing to count.

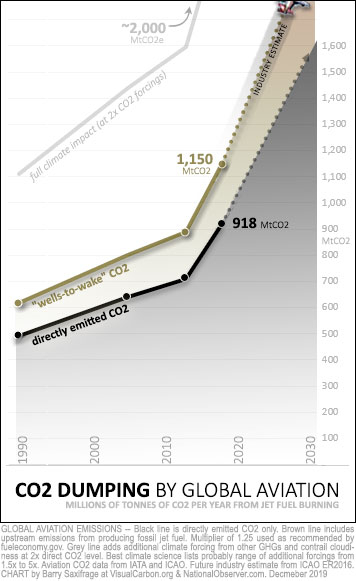

As my second chart shows, the upstream emissions from producing jet fuel (a.k.a. "wells-to-wake" accounting) pushes aviation's CO2 impact significantly higher.

On top of that, the best climate science indicates that burning jet fuel in the upper atmosphere creates additional warming from other greenhouse gases and contrail cloudiness. While less well quantified, the full climate impact is estimated to be between 1.5 times CO2 at the low end, and five times CO2 at the high end. The grey line in the chart shows that at two times CO2, aviation's full climate impact already exceeds two billion tonnes.

Is it any wonder that kids are taking to the streets in worldwide protests to try to save themselves? As Greta Thunberg laments to Time magazine: “We can’t just continue living as if there was no tomorrow, because there is a tomorrow.”

One of the world's dirtiest industries

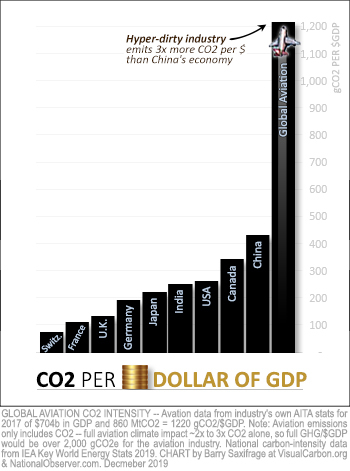

Aviation's soaring climate pollution carries another large, though little appreciated, climate risk: the industry produces very little value from each tonne of CO2 it emits. The economists' term is "high carbon intensity," while a more colloquial term is dirty dollars.

My next chart lets you quickly compare how the global aviation industry compares to some of the world's major economies.

The industry's own GDP and CO2 numbers show they emit around 1,200 grams of CO2 per dollar of GDP they produce. For context, China's coal-choked economy emits only a third as much CO2 per dollar.

The aviation industry says: "If aviation were a country, it would rank 20th in size by GDP (similar to Switzerland)." What they don't mention, but the chart shows clearly, is that the industry dumps 15 times more climate pollution than Switzerland to get there.

However you slice it, there is growing risk — to industry, investors and humanity — from driving such a breakneck expansion of a "three-times-dirtier-than-China" industry into the teeth of the gathering climate storm.

But, aren't there technology solutions coming — like electric jetliners and biofuels — that will clean up flying? Good question. Let's next take a look at what the industry is planning for each, and you can decide for yourself.

How much can electric planes help?

There are many hopeful stories about electric planes these days. Can e-flight solve aviation's climate problem?

I wish!

I love travelling. But I also decided to stop flying more than a decade ago because of the oversized climate damage even one long-distance flight creates.

So, I'd be one of the first and most eager customers for zero-emissions electric flights. I'm an e-flight fanboy and try to keep up with the technology closely. One can dream…

Unfortunately, as the industry regularly points out, 80 per cent of aviation CO2 is emitted from flights over 1,500 kilometres in length. Sadly, none of the dozens of proposed all-electric airplanes plan to fly anywhere close to that far. As a study this year by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) concluded: "Electrifying commercial aircraft does not appear feasible in the 2050 time frame, except for short-haul flights."

And even if humanity electrified every short-haul flight, it would not stop aviation emissions from soaring. To illustrate why, I've updated my first chart to include a line showing CO2 from flights over 1,500 km.

As this rising orange line makes clear, long-haul flights are increasing so fast they will exceed today's total aviation emissions in just five years.

So even an immediate global ban on all flights less than 1,500 km would be wiped out within five years by surging long-haul flight emissions.

In reality, switching all short-haul flights to clean electricity will take decades. Huge fleets of new electric jetliners need to be developed, tested and produced. Existing jetliners written off. Every airport will need massive new electricity supplies capable of fast-charging multiple jetliners at a time. And all those super-grids will need to be powered by newly developed zero-carbon electricity installations. That's a lot of money and effort to not solve the problem. That's doubly true when we already have solutions for short-haul distances via low-carbon ground transportation.

So, if electric planes can't stop jet fuel CO2 from soaring ever upward, what can?

The industry claims that huge quantities of bio-jet fuel are the only way to lower the amount of CO2 they emit. A growing number of climate-concerned people are instead advocating fewer flights to ensure aviation's CO2 emissions start falling. Will the climate solution to flying come from mountains of bio-jet or capping flights? Or both?

How much can bio-jet help?

The industry says "sustainable aviation fuels" are crucial to their "licence to grow." As a Boeing executive told Bloomberg: "There is a tremendous amount of determination to make biofuel work because we just don’t have any alternative." Well, other than capping the rise in flights. The International Renewable Energy Association (IRENA) says bio-jet is the "only real option to achieve significant reductions in aviation emissions by 2050." Again, other than halting flight expansion, that is.

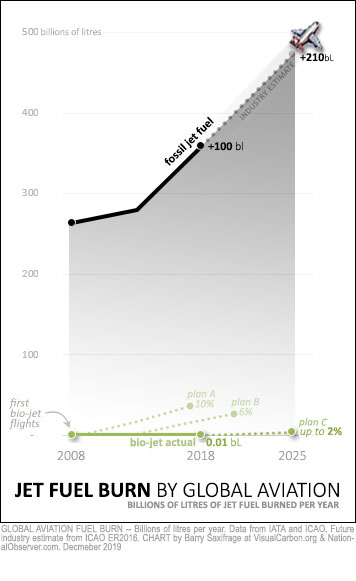

Unfortunately, bio-jet is languishing as a "fuel nobody makes in volume." My next chart tells the story. It shows jet fuel use, in billions of litres per year.

The bottom green line shows bio-jet plans versus production, since the first bio-jet flights a decade ago.

Back in 2009, the industry heralded a clean future via bio-jet. "Look at our amazing work on biofuels. They have the potential to reduce our carbon footprint by up to 80 per cent. IATA set a target of 10 per cent alternative fuels by 2017." (H/T Dan Rutherford at ICCT)

But when 2017 arrived, the airlines bought thousands of times less than that — just 0.002 per cent of their fuel use. So much for plan "A."

In the meantime, the airlines increased their fossil jet fuel purchases by 10,000 times as much. In fact, fossil jet fuel use is now rising more every four hours (+10 million litres) than bio-jet has managed to do in a decade (+7 million litres).

Ever-shrinking targets

My chart also lets you see the discouraging trend toward ever-smaller bio-jet targets. In 2009, the industry's target was for 10 per cent bio-jet by 2017. By 2011, they cut it sharply to six per cent and pushed out five years. Now, in 2019, the target has been slashed to just one or two per cent by 2025. And even that amount is considered unlikely unless governments jump in soon to help pay for it.

Collapsing investment

With the aviation industry unwilling to pay the higher price of bio-jet, production has faltered. Indeed, global investment in all biofuels has fallen off a cliff — down 90 per cent from a decade ago.

At this point, promises of gigantic surges in bio-jet — like the rapid 10,000-fold increase underpinning the ICAO's climate solution called "Vision 2050" — are so wildly beyond what is actually being funded that they've become just another form of predatory climate delay like "clean coal" and "clean diesel."

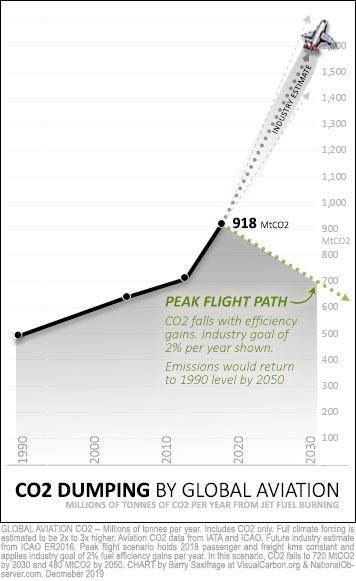

Peak flight?

“I’ve decided to stop flying because I want to practice as I preach, to create opinion and to lower my own emissions... If a large number of people do this, then it will. It sends a message that we are in a crisis and have to change our behaviour.”

– Greta Thunberg, 16-year-old Swedish climate strike leader

With aviation's emissions soaring and its promised climate solutions failing to arrive, a growing number of climate-concerned people are boycotting flying and advocating a halt to flight expansion ("peak flights").

The most famous flight boycotter, of course, is Greta Thunberg. The worldwide media coverage of her efforts to avoid jet travel has propelled the threat of rising flight emissions into the global conversation. Her nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize, followed by being named Person of the Year by Time magazine, has amplified it further. The idea of fewer fossil-fuelled flights has emerged into both personal and policy discussions.

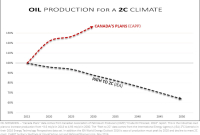

To illustrate the potential climate benefits of capping flight levels, I've added a "peak flights" scenario in which flights remain at current levels. It's the falling dotted green CO2 line.

As you can see, flight emissions would fall steadily even as the amount of flying stayed the same. The falling CO2 would come from the industry's ongoing efficiency gains. In this illustrative scenario, I've assumed the industry meets its target of increasing fuel efficiency by two per cent each year.

If the world wants to quickly and consistently cut the amount of climate pollution from the aviation industry, "peak flight" is the only solution being discussed that can do it. In fact, "peak flight" has the potential to cut aviation emissions in half by 2050, all without reducing today's level of flights.

Instant climate progress. No techno-miracle required. And, as a bonus, we get to avoid ugly global struggles over food-versus-fuel, flying-versus-forests and who gets access to the planet's remaining biomass. It's no wonder that enthusiasm for limiting flights is taking off.

Comments

Radical but effective. Slapping on a $300 per ton carbon tax would probably work too. Given the choice, the airlines would probably opt for the carbon tax rather than accept "no-growth". They will fight tooth & nail to avoid both.

Yes, pricing climate pollution as you suggest is one effective way to reduce emissions. The two big stumbling blocks to taxing jet fuel are (1) that jet fuel for international flights (67% of all jet fuel use) is exempt from national taxes and (2) creating a situation where only the wealthiest can fly might not be politically viable. Aviation is cheap because it doesn't pay fuel taxes like ground transport does...so it is both the fastest and the cheapest way to fry the climate and acidify the oceans. The industry has fought tooth and nail to prevent EU from including it in its carbon pricing markets for example. And wealthy folks love a system that limits access to carbon fuel benefits to those that can pay. Alternatives I've seen proposed include rationing and rising fees with each additional flight taken each year.

Good work, Barry. Well done. And, yes, sadly, a good reminder to deal more rapidly with our travel habits.

I appreciate you writing and letting me know that the article was interesting. And I agree that we need to rapidly shift to more leisurely travel modes that are less damaging to our kids' futures.

I've not flown for over 5 years now, and don't miss the hassles, the feelings of being treated like cattle, the the small seats, etc. I had to laugh at my brother recently as he battled with Air Canada over his naive attempt to actually use airline points; what a joke; 'the gift that keeps on not giving'. Cutting out flying was one of the easiest adjustments I've made as a result of a decision some years back to change to a low-carbon lifestyle.

Instead, I look for more local destinations I can drive to.....with my EV of course. With the Tesla super-charger network stretching across Canada now, and with an RV power adapter, even out-of-the-way locations are accessible by EV these days.

As the saying goes, "flying's for the birds"!

I certainly agree, James! Giving up fossil jet-setting has been far easier than I expected as well. Part of that is because slower travel has turned out to be far more rewarding than I expected. Part of it is because I get to more live in step with my core values, which is a huge relief.

And ditto on the Tesla road tripping. The autopilot and superchargers have made our long-distance road-trips-instead-of-flying a pleasure. Thanks for the tip about RV power adapter.

The effect of this article is nothing short of terrifying, and while I understand that you want readers pay to attention, the author appears to have missed an important part of the story.

It is the IATA’s Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) which promises carbon-neutral growth on international flights from 2020. The success of this is by no means assured, and there are a number of notable loopholes, such as

1. That domestic flights are not covered by the cap.

2. The current level of emissions will not be offset.

3. It will put the offsetting industry under pressure to expand rapidly ($40 billion to offset 2.6 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions).

4. It will only be as effective as the offsets (along with other efficiencies) prove to be.

5. The industry is self-policing and the first phase is voluntary, with approximately 80% of airlines expected to participate.

I am not intending to defend the industry, but would like to see your newspaper continue to write about this topic with an emphasis on how governments and civil society at large must watch the airline industry closely as they embark on this program. If it isn’t done well enough, we all need to push them aggressively for a new international solution to the growth of their emissions.

Thanks for writing, Adrienne. I do follow CORSIA closely. And I've written about it in the past on the National Observer. You have a good list of concerns about it. I would add to your list:

6. The huge threat of locking in dangerous levels of fossil fuel burning by building out trillions of dollars in infrastructure that require far too much fossil burning for decades.

7. The industry's refusal to take responsibility for their very sizable non-CO2 climate impacts

8. The industry's lack of any plan that will ever reduce climate pollution from aviation. For many, including myself, we are far too deep into the climate crisis for any industry to be increasing emissions while lacking any pathway to bring them down to zero emissions. Those industries are climate rogues at this point in my view.

9. The history of big promises that they have not followed through on: failure to fund bio-fuels as promised, CORSIA diminished timing and scope, cancelling of hyped electric plane research projects, successful efforts to prevent equivalent levels of fuel taxes on jet fuel as paid by ground transportation, blocking of EU ETS being applied to international jet travel. For those of us that follow the industry climate promises closely, each new one is like Lucy holding the football for Charlie Brown and promising "this time" to not yank it away when the time comes to act.

I will definitely continue to cover CORSIA, but I'm very doubtful the industry will implement anything that will reduce their climate emissions as required to pass along a safe and sane climate future to our kids and grandkids generations.

The data seems very strange. Do you understand why the rate of CO_2 emission from aviation increases so sharply and dramatically in or around 2014? Could you publish your numbers and give links to your sources? Superficially, it appears that the numbers for your last data point are not calibrated correctly compared to the previous data points.

Hi John, the rise is really amazing, eh?

Data sources for recent years can be found in IATA fact sheets such as: https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/pressroom/fact-sheets/fact-shee…. I've been collecting them for years. The IATA has set 2005 as their baseline year for climate targets, much like Canada has. Until recently they were reporting 640 MtCO2 as the 2005 baseline. They recently removed the webpages list that number and have increased the baseline to 650 MtCO2 as listed here: https://aviationbenefits.org/media/166838/fact-sheet_4_aviation-2050-an… . This reduces the rate of increase from 1990 to 2014 a bit which makes the current surge even greater. For 1990 baseline most people use ICAO data of around 500 MtCO2 as reported in any of their ICAO Environmental Reports such as this one from 2010: https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/documents/environmentrepo…

I'm not sure that "amazing" is quite the right word. Perhaps "incredible" would be more appropriate.

It looks like the dramatic increase in slope that you see is mainly the result of data-point selection. The data are rather noisy (presumably for economic reasons), and sometimes annual jet fuel consumption actually decreases. To give an extreme example, had you chosen your reference slope to be the period, 2009-2012, the annual consumption of jet fuel would have increased by a total of 8 billion gal/yr over three years. From 2012 to 2018, consumption increased by only 12 billion gal/year over six years - a much slower rate of increase. I agree that the most recent rates of increase of jet fuel consumption are larger than in the past, but not by a factor of 4! Increased consumption is more likely related to the increase in GDP.

There'd have to be "full load" policies as well as some sort of rationing ... it's hardly as though most of the ppl "paying for" the downside are themselves frequent fliers ... or even fliers at all.

I fail to understand the necessity of vacations abroad to the extent of several flights a year.

The whole untrammeled growth thing is also all bound up in income inequality. Both coming and going.

Hi Barry,

As I stare at the plastic container holding my breakfast yogurt, I note the (relatively new) calorie labelling and wonder if governments couldn’t mandate ‘catbon labelling’ for all travel tickets. At a minimum it may raise awareness? It might empower consumers a bit more and allow companies that book travel to differentiate their offerings based on environmental impact. If it was evenly applied based on something like an iso company audit, maybe based on practices, inputs and equipment and ranked/rewarded companies within a category like airlines and was per-product it might even help incent and be ‘one more thing’ added to the pile of things that together will help a bit.

Why are we not talking about airships, which seem to represent a no-emissions way to fly? Not as fast as a jetliner, but far more pleasant, according to the historical record. I've written about this possibility here: https://thegreeninterview.com/blog/2019/06/19/the-green-way-to-fly/

Silver Donald Cameron

What are the practical alternatives to travel by jet plane? Are there less polluting alternatives? More efficient aircraft? Dirigibles? Video conferencing in lieu of travel? Return to trains and passenger ships?

What else? Which alternatives are growing in use? What incentives are required to shift the growth away from jet planes to more responsible alternatives?

I used to believe there would come a day when governments would have no choice, in order to save the planet from impending doom, but to impose bans on non-essential air travel. I no longer believe that. They lack the collective balls to do anything approaching such a progressive move. And the mindless hedonists who only want to get to the sun as many times as they possibly can, with zero thought for the consequences, wouldn't stand for it, anyway. There'd be revolution in the streets. Which raises the question.....are we worth saving? www.PlanetInPeril.ca

Problem occurs when you do not have a level playing field, put a price on carbon, then let the market decide what technologies to use, since 1992 we have seen the result of setting reduction goals that have no real consequences, low hanging fruit is picked, but that was likely to happen anyway.

Your article is insightful Barry, but I wonder why you do not raise the possibility in the future of using Clean Electricity to produce Hydrogen to power planes?..I realize that we are not there yet, but the technology seems to be just around the corner. It would eliminate the release of C02 gasses in the Upper Atmosphere and be much more easily adapted to existing technologies of flight.

Clean hydrogen to power planes has been just around the corner since 1975 (pic at https://www.quora.com/Is-zero-emission-air-travel-possible/answer/Graha… . Note the allocation of space within the fuselage).

Nuclear-generated kerosene, generated from atmospheric CO2 and water, would eliminate the carbon footprint. The high-altitude water vapour footprint would still exist. How serious that is, I'm not certain, but if it's very serious, a solution to it that also is a slight improvement on kerosene, both in mass *and in volume*, exists.