Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

There’s good news and bad news about Canada’s 2030 climate target.

The good news is that for the first time, Canada has proposed a way to meet a climate target. The government’s recently announced Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy (HEHE) plan contains enough new climate policy proposals that, if implemented, will allow Canada to reach its 2030 target.

The bad news is, promises don’t cut emissions. Laws do. Climate laws enacted by Canadian politicians to date don’t come anywhere close to meeting our 2030 target. With time running out and a gigantic emissions gap to close, Canada needs to enact climate laws now — not just add to the "maybe later" pile.

For an example of how a proposed policy ends up delayed and watered down, consider Ottawa’s long-promised Clean Fuel Standard. It was going to be broadly applied and lead to a reduction of 30 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) per year. But the policy still hasn’t been enacted, and the latest draft has a narrower scope that is expected to cut only 20 MtCO2 per year. As we will see in more detail below, Canada needs a lot more climate laws on the books.

The ugly part of the plan is how it ignores the flood of emissions pouring out of Canada’s managed forestry sector and instead claims this sector is a source of "net GHG removals." Over the last decade, logging emissions have vastly exceeded what our nation’s managed forests have absorbed. This carbon imbalance has created a flood of net GHG additions into, not removals from, the atmosphere, worsening the climate crisis.

Pencil-pushing this huge source of CO2 off the books won’t fool the climate. We need to rein in all our excess CO2 emissions if we want a safe and sane climate future.

To illustrate these good, bad and ugly parts of Canada’s 2030 plan, I’ve created a series of charts from the government’s latest emissions inventory and projections.

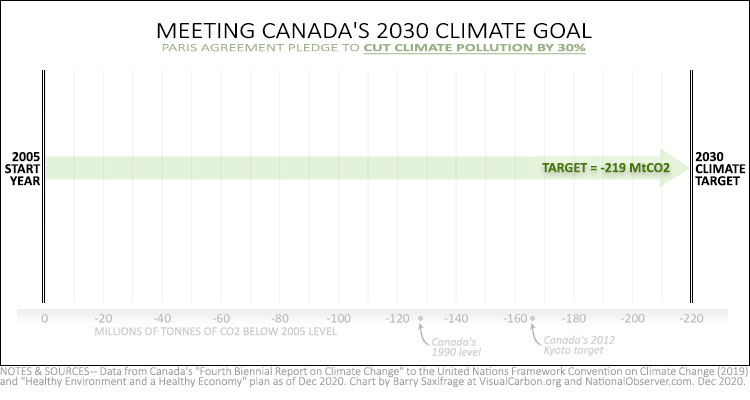

The 2030 goal

First, the goal.

Both the Harper Conservative government and Trudeau Liberal government that followed committed Canada to the same climate target for 2030.

That target, pledged under the global Paris Agreement, is to reduce our climate pollution to 30 per cent below our 2005 levels. That works out to a reduction of 219 MtCO2 in annual emissions.

To illustrate this visually, my first chart shows that task as a green arrow stretching from the 2005 starting line on the left, to the 2030 goal line on the right.

Next, let’s see how far Canada’s current federal and provincial climate policies will get us.

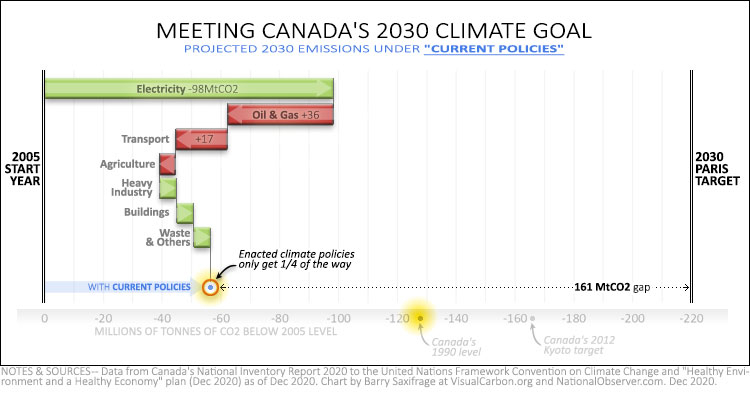

The bad: Current climate policies

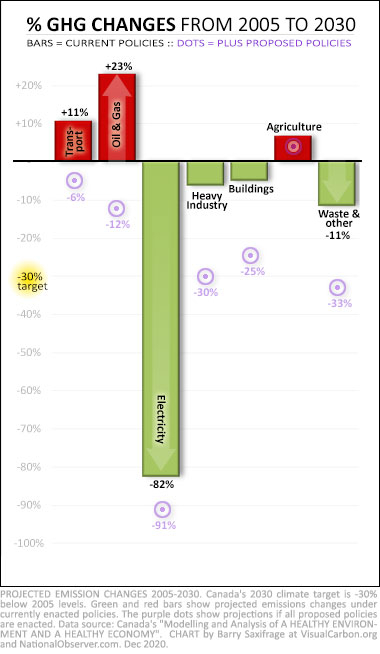

The chart below now includes coloured bars for each sector of the economy. The length of these bars indicates the projected change in emissions between 2005 and 2030 given current policies.

The green bars, like the top one for the electricity sector, show sectors that are projected to reduce climate pollution under current policies. Each of these move the nation closer to the goal line. In contrast, the red bars show sectors on track to increase climate pollution above the 2005 level. These push the country’s progress backwards.

The blue arrow in the bottom left shows the net result for Canada. As you can see, the policies actually on the books fall far short of what is needed.

Canadian politicians have been promising to cut our too-high emissions for 30 years. And yet, all the climate laws enacted over those three decades are too weak to even knock our emissions back to the 1990 starting line, which was already too high.

This can be seen by comparing the chart’s two yellow highlights. The one on the right shows Canada's 1990 emissions level. The one on the left is where our emissions are expected to be a decade from now under current policies — still 70 MtCO2 higher per year than they were in 1990.

Decades of Canada’s climate laws continue to be, even now in 2021, massively undersized compared to Canada’s promises.

Before moving on to look at the current crop of promises, it’s worth underlining the three sectors that dominate the chart above.

Electricity — As the top green bar on the chart shows, under current policies, almost all of Canada’s emissions cuts are expected to come from the electricity generation sector. It’s on track to reduce its annual emissions by nearly 100 MtCO2. This is being driven by two major climate policies. First, Ontario’s decision to eliminate coal-fired generation. Second, laws passed by the federal government to phase out coal-fired generation nationwide.

Oil and gas — At the other extreme, the red bar for the oil and gas extraction sector shows that it is on track to significantly increase its climate pollution. Under current policies, this sector is projected to emit 36 MtCO2 more in 2030 than it did in 2005. The primary driver is rising amounts of fossil carbon being extracted by the Alberta oilsands industry.

Transportation — The other big red bar on the chart is the transportation sector. Canadians continue to purchase and drive the world’s most climate-polluting cars. Clearly, all the climate laws enacted so far haven’t done much to rein in this pollution beast. As a result, transportation emissions under current policies are projected to be 17 MtCO2 higher per year by 2030 than they were in 2005.

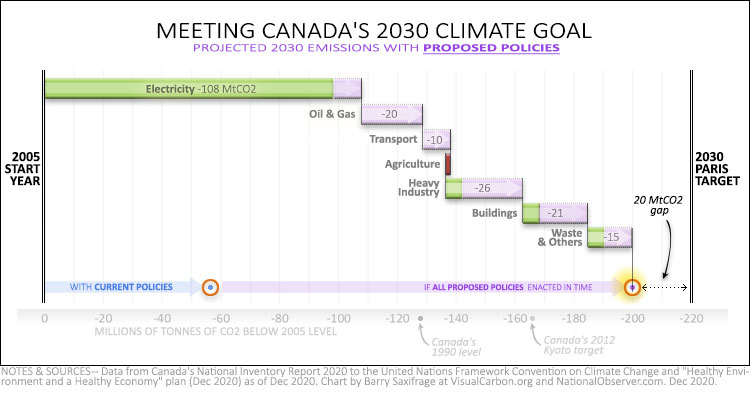

The good: Proposed policies

Now let’s look at the good news side: potential reductions from all the promised climate policies.

I’ve added purple bars to the chart to show the projected impact of all the proposed climate policies. (Note: These projections assume all proposed policies get enacted at full strength and on time.)

As you can see, these would lower Canada’s 2030 emissions to within 20 MtCO2 of our target. Getting that close would certainly count as good news in my book given Canada’s huge over-polluting misses so far.

And there is additional good news revealed by all those purple bars. Every sector, except agriculture, would be required to reduce emissions. That would also be a first for Canada. So far, Canada’s two most climate polluting sectors — oil and gas extraction, and transportation — have been allowed to increase emissions.

This failure to rein in the two most-polluting sectors has been at the heart of Canada’s multi-decade climate failure. It will be a major step towards climate sanity in Canada when these two sectors start making big emissions cuts.

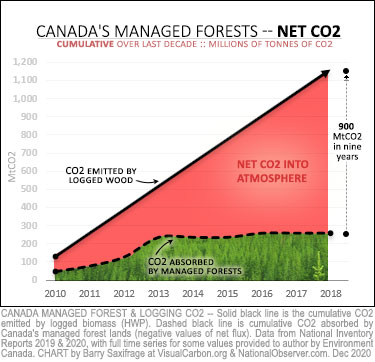

The ugly: Forestry offsets

And what about that remaining 20 MtCO2 gap to the target?

The government says it plans to close it using "net GHG removals" from Canada’s forestry sector.

The idea that our forestry sector claims to remove climate pollution from the atmosphere is mind-boggling to me. Take a look at this next chart showing forest carbon data from Canada’s latest official National Inventory Report.

The rising black line on the chart shows the CO2 emitted by all the wood logged in Canada. It has totalled nearly 1,200 MtCO2 over the last decade. To be clear, this is the CO2 emitted into the atmosphere when the wood was burned for energy, or rotted after being discarded.

Now compare those CO2 emissions from the logging sector, to the green area on that chart. That’s how much CO2 Canada’s managed forests absorbed over those years — just 300 MtCO2.

The excess 900 MtCO2, shown in red, has been piling up in our atmosphere, worsening the climate crisis. This flood of CO2 has grown into a serious and surging climate threat. Pretending it doesn’t exist won’t make the threat magically disappear.

If we want to stop the climate crisis from worsening, we must shut down this rising tide of CO2 into the atmosphere. It now totals more than a billion tonnes of CO2 over the last decade. That’s more than most Canadian sectors or provinces emitted over those years.

Ottawa’s 2030 climate plan, however, ignores these emissions. That certainly hasn’t been easy, because all those emissions used to be on Canada’s official carbon books. The effort to push this CO2 off the books has required a series of creative carbon accounting changes over the last few years.

But pencil-pushing climate pollution off the books doesn’t remove it from the atmosphere.

If we want a safe climate future, then Ottawa’s climate plans must stop contorting this rising CO2 flood into supposed carbon credits — and start reducing the threat.

Sharing the burden

Above, we saw how Canada’s 2030 plan aims to meet the target. I’ll finish up by looking at how that plan divides the burden of emission reductions across the sectors.

My next chart lets you see the percentage changes projected for each.

The bars show changes under current policies.

For example, the red bar for the oil and gas sector shows that it would be allowed to emit 23 per cent more in 2030 than it did in 2005 under current laws.

Conversely, the green bar for the electricity sector shows that its emissions would fall 82 per cent under current laws.

And the purple dots show the changes expected under proposed policies.

In this more hopeful scenario, all sectors except agriculture would end up with lower emissions in 2030 than in 2005.

But the percentage of cuts vary widely.

For example, Canada’s two most climate polluting sectors would reduce emissions by a smaller percentage than the national average. Transportation would be targeted for just a six per cent reduction from 2005.

Three other sectors would be targeted for reductions that are roughly in line with the national target of 30 per cent. These are the heavy industry sector, buildings and the waste sector.

And the electricity sector would be targeted for an impressive 91 per cent reduction from its 2005 level by 2030. This rapid decarbonizing of an entire sector has been the big climate success story for Canada.

But this success now poses a thorny policy problem going forward.

As the charts above have shown, Canada has relied on this one sector to make nearly all the nation’s big emissions cuts. But that strategy won’t work anymore because there’s just not enough electricity sector emissions left to cut. This is now forcing Canada to find big emissions cuts elsewhere. And that means Ottawa must now target the emissions from oil and gas and transportation sectors to make future progress.

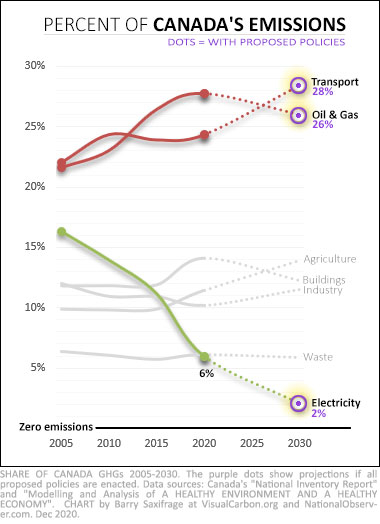

My next chart shows why.

On this chart, each sector has a line that shows its share of Canada’s emissions since 2005.

The green line shows the electricity sector. Its emissions are currently down to just six per cent of the nation’s total. This is now the least-emitting sector in Canada. And it’s headed to only two per cent by 2030.

In contrast, the red lines show that the oil and gas and transport sectors’ emissions have steadily increased their dominance of Canada’s emissions. Combined, they now emit over half of Canada’s climate pollution.

And as the purple dots at the end of those lines show, their combined share is expected to be even higher by 2030 — even with all the newly proposed policies in the HEHE plan.

Simple math requires the biggest emissions cuts to now come from these two sectors. That’s because they are now the lion’s share of the problem.

The hopeful news is that Canada has shown, via its electricity sector, that it can enact the laws needed to virtually eliminate climate pollution within 25 years from one of its major emitting sector. Now Ottawa needs to act just as quickly to rein in its remaining super-emitting sectors.

Comments

Three issues:

1) The Trudeau govt is still advertising that Canada's climate plan has room for new export pipelines transporting oilsands bitumen.

Kirsten Hillman, Canada's ambassador to the U.S.: "Keystone XL fits within Canada’s climate plan"

https://www.nationalobserver.com/2021/01/17/news/transition-biden-order…

That's true only if Canada's climate plan is to miss its inadequate targets by miles.

2) Gross Under-reporting of Emissions

As multiple studies based on actual measurements show, Canada's oil & gas industry grossly under-reports its emissions — of all types. The industry's emission stats are fiction.

Grossly under-reported oilsands emissions do nothing but climb year after year. AB's emissions show no sign of falling.

Under climate leader Trudeau, Canada's GHG emissions in 2018 hit levels not seen in a decade. Not on track to meet 2030 and 2050 targets.

Oilsands expansion enabled by new export pipelines will prevent Canada from meeting its inadequate targets for decades.

3) "The ugly part of the plan is how it ignores the flood of emissions pouring out of Canada’s managed forestry sector and instead claims this sector is a source of 'net GHG removals.' Over the last decade, logging emissions have vastly exceeded what our nation’s managed forests have absorbed. This carbon imbalance has created a flood of net GHG additions into, not removals from, the atmosphere, worsening the climate crisis."

Due to more forest fires and insect infestations, Canada's managed forests have been a net carbon SOURCE since the turn of the century, not a sink.

Adding to our man-made totals, not subtracting.

NRCan: "In 2016, total net emissions of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) from Canada’s managed forests (forest lands managed for timber production) were about 78 million tonnes (Mt), meaning that they were a net source of emissions.

"Total net emissions are calculated by adding emissions/removals caused by human activities in Canada’s managed forests to emissions/removals caused by large-scale natural disturbances in Canada’s managed forests."

"Indicator: Carbon emissions and removals"

https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/our-natural-resources/forests-forestry/state-ca…

*

20 Mt CO2e is the net amount of carbon stored by "forest management activities, such as harvesting, slash pile burning and regeneration, as well as the use and disposal of harvested wood products". That figure does not include the much larger net emissions due to natural disturbances (fire and infestation).

*

NRCan: "The total net emissions and removals from Canada’s managed forests, taking into account both human activities and natural disturbances, were about 78 Mt CO2e (–20 + 98 = 78) in 2016. This includes emissions from wood harvested in Canada and used in Canada and abroad."

*

Going back to 1990, Canada's managed forests have only rarely been carbon sinks, and the amount they absorbed was tiny.

In 2007, the Harper Govt decided to leave Canada's forests out of its Kyoto equation, because they would be a liability, not an asset.

"Canada's forests, once huge help on greenhouse gases, now contribute to climate change" (Chicago Tribune)

• www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/chi-canada-trees_wittjan02-stor…

*

In 2017, B.C. wildfires emitted c 190 Mt of carbon — more than triple B.C.’s annual (man-made) carbon footprint.

(2018 report: "Addressing the New Normal: 21st Century Disaster Management in British Columbia")

Thanks for the comment. Those are all good points.

Also, regarding methane emissions, new European satellites can now detect methane emissions at fine detail for the first time. This will revolutionize the accounting and assigning of responsibility for methane emissions worldwide going forward. The days of under-reporting and greenwashing on methane are just about over. Any "plans" that have relied on under-counting methane will fall apart.

The part of this commentary that catches my eye is the issue of automobiles. Yes cars are contributing to the problem. However, I believe the biggest contributors to the problem from a transportation point of view are transport trucks and airplanes. These seem to be ignored in this article. Everyone in Canada cannot afford to own an electric car. Also, the current electricity grid could not generate enough power to charge all those cars. Then you have the question of what form of fuel is going to be used to increase electricity generation and how much pollution is that going to generate. If you are not gaining in the overall reduction of emissions then what is the point in promoting electric cars. I would venture to say airplanes and transport trucks are two of the biggest polluters in Canada in terms of transportation.

Just one further thought. Why is there no mention of Mr. Trudeau's promise to plant millions of trees which he made in his first run for prime minister and reiterated lately. Is this going to be later on promoted as one of his major achievements around pollution associated with forestry.

What do you mean, everyone in Canada cannot afford to own an electric car? That's what policy is for. I bought an electric car; because of subsidies in BC at the time it was cheaper than buying a similar ICE car would have been.

And no, increased electricity generation is not going to involve "fuel". It's going to involve solar panels and wind turbines. Meanwhile, did you look at those charts? The projection is electricity generation representing 2% of carbon emissions. Double electricity generation to power cars, electrified industry etc. and it would still only be 4%--even if that doubling used the same mix as the existing electricity production, which it wouldn't.

Finally, while it's certainly a good idea to tackle transport trucks and planes, other articles I've read suggest the percentages aren't that large. We cannot ignore personal transport. Probably wise for that to involve as much increase in mass transit provision as shift to electric vehicles, but individual cars are not going to go away any time soon, and they should be electric. Transport trucks should be electric, and in any case should be de-emphasized in favour of a return to more efficient rail which should also be electric, but that is not an excuse to skip cars, which are a huge deal emissions-wise.

You are fortunate enough to live in a Province where jobs are plentiful and the rate of pay is on the upper end of the scale. I live in the Maritimes where income is not as rosy. Electric cars at 50K plus each are not within my budget. Also, we have a sparse population and a lot of travel is required to move between places. In other words we would need a substantial increase in the number of charging stations that are available within the Province. Do you see the carbon tax paying for things like wind turbines or wind power? I do agree railways should probably be providing a larger part in the transportation area. Unfortunately goods cannot get to the customer without being trucked from rail to the actual location of the business. If hydrogen powered vehicles could be perfected that would be the way to go. I

Unfortunately, per truck kilometer driven, hydrogen requires 3 to 4 times more electricity to create than it does to just power an EV truck directly. Hydrogen significantly increases the amount of new climate safe electricity Canada would need to build out. Its hard to store and dangerous too. EV tech is vastly more efficient and safer.

Mr. Saxifrage, thanks for the information on hydrogen. I was aware it was dangerous but not aware it used up a lot of electricity to produce. I am still left wondering about transport trucks and airplanes and what role these play in the environmental issues. Are there statistics available providing an estimate of the carbon produced by these forms of transportation during good times as opposed to a pandemic.

All good points. Especially agree that the role of government is to help people transition from fossil burning to clean energy. Many European nations have done this in personal transport by highly taxing sales of new gas burning vehicles and using that money to fund incentives for EVs. No net revenue lost. In my view a little discussed reason Canada govt hasn't incentivized EVs more is because new gas-burning cars and trucks lock-in decades more of paying customers for the oil companies. Petro-state mentality puts petro-industry needs first.

One quick data point: Passenger cars and trucks are sadly the main source of transport emissions in Canada -- 90 MtCO2 in 2018. Freight is 78 MtCO2. Passenger vehicles emit more than any other sectors including Heavy Industry or all the buildings in Canada. The average new car/truck bought by Canadians today will emit 66 tCO2 just from burning gasoline. There's safe climate future in which Canadians keep buying the world's most climate polluting cars and trucks.

Thank you for a great analysis. The Buildings sector is also somewhat "ugly" with proposed policies that will only get emissions back to where there were in 2005. The current proposals focus mostly incentives for homeowners for minor improvements, and low cost financing for various building types that will encourage some deep retrofits but nowhere near enough to meet the 100% target by 2050. To do that we will need, as soon as possible, building codes for existing buildings that require deep retrofits every time a home or building changes hands or undergoes a renovation. The federal government is promising a code covering "major alterations" by 2022, but this code then has to be adopted by each province and applied at the local level. Only the City of Vancouver can do this right now. We also need to rapidly commercialize prefabricated building cladding and window replacement systems to meet this code requirement that can be applied without inconvenience, and by all contractors. This means targeted incentives to drive down costs through economies of scale. Finally we need to support the development of a fully trained retrofit industry and workforce so that retrofit codes can be quickly and easily applied. Its time up the game on retrofits.

Great points Mr. Peters. Maybe part of the money being collected from the carbon tax could be returned to home owners in the form of a contribution by the Federal Government to upgrade your home to become more energy efficient and to reduce heating or air conditioning requirements thereby reducing the overall emissions contributing to climate change.

I agree.

Increasing the energy efficiency of buildings would be a key chapter in a National Climate Transition Plan, along with the improvements to urbanism you alluded to. The trouble is, where is the Plan? Who in the federal cabinet was designated to address climate transition planning? Why haven't we seen a comprehensive map for decarbonizing the economy, though "action on climate" has been repeated over and over since 2015? Six years in, and the Liberals have provided a few peanuts scattered randomly on the ground while spending all of two weeks to purchase a pipeline.

My hunch is that ministers are pestered daily by moneyed industry lobbyists to fall short of completing a plan, or they cannot see beyond the rim of their own silos. In addition to being wilfully blind to the reality that repairing the planetary biosphere IS the economy, ministers are collectively afraid of giving the opposition a target. This is what we get when we elect milquetoast career politicians who cannot stand up straight and be nourished by the principle of looking out for future generations by supporting science first and foremost over political donations, cheesy photo-ops and empty rhetoric seldom backed by genuinely meaningful acts.

Warnings by scientists are now ubiquitous. Great charts by people like Barry Saxifrage, and independent opinion leadership by outfits like this online journal and a handful of other media are now a run-of-the-mill industry. Still, none of these have slowed the flow of smily face politicos issuing hourly lying, vacuous non-statements for general consumption by the masses. We've had years and years of this crap, and even more protest against the weak action, or total lack of it, and still nothing gets done because of the foundational weaknesses embedded in our leadership.

The conversation really needs to be changed. That will only start from the bottom where the people live. The politicians have never earned our trust. There is too much private money in public officialdom.

I have recently been whining to anyone who would listen that, even though the feds have been seized by the COVID crisis, NRCan (the likely source of any support for retrofits) surely cannot have a severe COVID burden, so why is nothing forthcoming (like they haven't done this before)?

To add another piece of cynicism, it dawnwed on me that incentives may be being held back for the rumoured federal election. More goodies to buy votes?

Some of the commentators here, such as Biggs and Botta, seem to have missed the point of Saxifrage's well-researched analysis, which is that the federal government has finally published a plan that really might be effective ("the good", according to Saxifrage). Yes, there are still weaknesses, which the analysis clearly identifies.

What I would like to say is that it is now time to stop complaining about imperfect politicians. If you genuinely want to live in a cleaner, healthier natural environment -- and want to see action on climate change -- then be part of those changes. Read the new "HEHE" report and follow the links to other plans, like proposals on hydrogen, etc. Figure out what you can do to help make this world better -- not perfect, just better ... and better than just complaining about imperfect politicians.

Thanks of the comment. I strongly agree that personal action is critical to making climate progress. As Greta Thunberg regularly says, we need to act like it is a crisis if we want people and politicians to treat it as a crisis. Talk without the walk isn't enough. Regarding the role of politicians, my view is that it is a mixed bag. There is "good" that we should give them credit for. And there is "bad" and "ugly" that requires people to keep pushing the politicians to fix if we want a safe and sane climate future.