Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

At the end of spring, Canada’s National Observer published a five-part series on the incredible odds stacked against First Nation students in northern Ontario who must travel hundreds of kilometres away from their families to get a high school education.

Our series reported on the trials facing students when moving south, how the grassroots staff in Indigenous education are not appropriately resourced, and how repercussions stemming from residential schools and colonization of northern First Nations disrupt education success. We wrote about how a revolving door of teachers brings precarity to classrooms on northern First Nations and how immersion language programs and on-the-land education must be prioritized to indigenize curriculums in schools up North.

Now, Canada’s National Observer is summarizing our reporting through data and an interactive map to show in a qualitative and quantitative sense what Kiera Brant-Birioukov, an Indigenous education researcher at York University, calls the “multi-pronged systemic discrimination” faced by Indigenous children and their families. Brant-Birioukov describes it as a double whammy of historical injustice coupled with contemporary inequities.

Although Canada’s National Observer cannot prove a correlation that moving south for a high school education leads to worse graduation outcomes, we can say that moving south and away from family support systems for school is one of the contributing factors to lower graduation rates, according to experts.

“There are kids down the street [who] get to go home at night, and [First Nation students in Thunder Bay] are making the ultimate sacrifice,” Brant-Birioukov said.

Using 2021 census data from Statistics Canada, Canada’s National Observer mapped the graduation rates for First Nations across Ontario.

The map gives a snapshot of the graduation rates for students aged 20 to 25. This does not consider the older individuals who may have gone back to obtain their high school diploma, according to census experts at StatCan. Communities with graduation numbers less than 10 were removed to ensure statistical accuracy. Statistics Canada’s methodology rounds census numbers to protect confidentiality, so any number between zero and 10 is randomly rounded to either zero or 10. Statistics Canada also randomly rounds any number greater than 10 to the nearest five, according to a Statistics Canada spokesperson.

The graphs below show the differing graduation rates for working-age populations. The first table is of non-remote First Nations, where students can stay with their families throughout high school. Those First Nations also have greater access to resources and less teacher turnover.

The graphs and map below show Canada’s National Observer's cumulative impact of the multi-prong systemic discrimination. The colour-coded graphs show the difference between remote First Nations and non-remote First Nations with road access.

However, our investigation found myriad contributing factors that impede graduation for First Nation students.

An odyssey nobody asked for

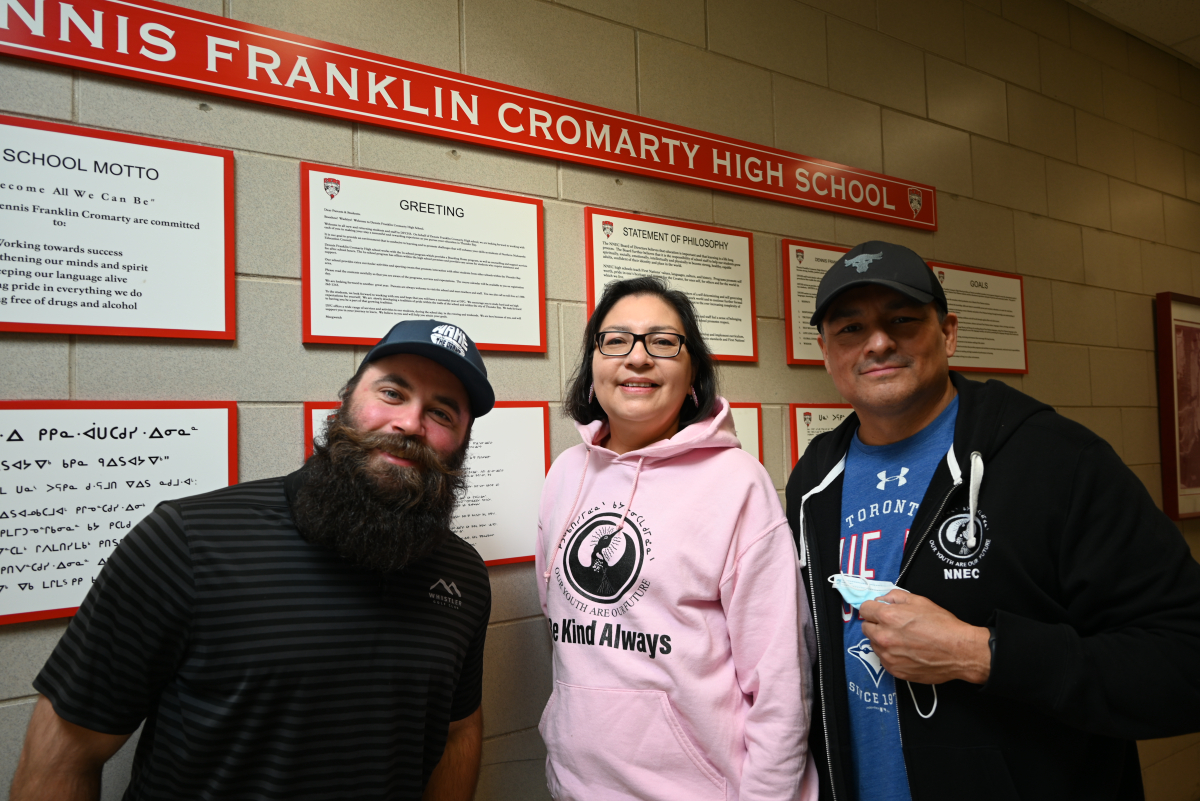

We spoke with students who chronicled their journeys south in Canada’s National Observer’s story while reporting on students at the Indigenous-led Dennis Franklin Cromarty High School in Thunder Bay. The school’s chief, Derek Monias, spoke about the challenges of arriving at 16 and being supported by his family. But he was lucky. His home community of Sandy Lake, about 600 kilometres north of Thunder Bay, has education up to Grade 10, while others at the school have to leave home at age 13 or 14.

Monias, a young student leader, believes students should control their education and decide when they want to leave their community to chase opportunity and independence because “everyone is different.”

“When they do it on their own time … their success goes way higher,” Monias said. “And I would make a push to have Grade 12 offered in the rez because they might not be ready to leave yet.”

Limited resources and Sisyhpus’ grant proposals

Sharon Nate, education director for Matawa Education, one of the Indigenous high schools in Thunder Bay, described the administrative burden of chasing project-specific funding on a short-term basis as leaving staff like an “elastic that is about to break.” Unlike Nate’s non-Indigenous counterparts, who receive stable funding, Indigenous high schools operate on piecemeal funding that can leave staff scrambling to fill positions or applying and reapplying for grants.

The conditions have made Nate an expert at stretching every single resource available.

“If you give me $10, I’ll stretch that as long as I can because that's the mindset I've been living in; that's my whole career,” she told Canada’s National Observer.

School infrastructure is also a concern, with Matawa Education facing uphill challenges to build its first gym. Due to construction costs, the school had to remove bleachers from the plans to cut costs. Meanwhile, down the street, a Thunder Bay high school had renovations on its new gym completed “in a matter of months.”

Colonially rooted crises within First Nations

In our reporting from Cat Lake First Nation, Canada’s National Observer spent time in the remote, fly-in community. Chief Russell Wesley emphasized the importance of the social determinants of life in a northern First Nation.

For example, an addiction emergency seen across Canada has hit a crisis point in First Nations. Yet, the First Nations must cope without specialized health care, relying instead on just one specialized health-care professional who treats the entire northern region via telehealth from Toronto. Wesley said if there were more doctors working inside First Nations, “then we could get somewhere.”

Like the rest of Canada, there is a housing and cost-of-living crisis in northern First Nations. Crowded, and sometimes even mouldy homes lead to poor health and education outcomes. If there is not enough infrastructure for children and if necessities are not met, then we cannot expect children to reach their full potential, Brant-Birioukov explained.

Some northern First Nations lack preschools and staffing. Without the staff or infrastructure for a preschool, many children can fall behind on literacy skills and miss out on interventions with early speech delays and learning disabilities, Brant-Birioukov said.

Brant-Birioukov points to research showing a high correlation between success in early childhood education and lifelong success in education and employment satisfaction and success.

“Especially as a mom, that just breaks my heart,” she said.

For Chief Wesley, education doesn’t begin and end in the classroom. It takes place daily with family and community, both of which have been infected by the traumas of residential schools and other colonial injustices.

“It's just not an education story — it's a social story,” he told Canada’s National Observer.

The revolving door of teachers

Canada’s National Observer discovered a teacher staffing crisis at First Nations schools that is often ignored by mainstream media. It’s reached a boiling point for Ken Sanderson, executive director for Teach For Canada-Gakinaamaage, a non-profit helping First Nations staff their schools.

High turnover carries a burden on First Nation students by having to build and rebuild trusting relationships with non-Indigenous teachers, making it difficult for children to become excited about lessons and learning, he said.

Sanderson is calling on governments, particularly the federal government, to incentivize teachers to move North and stay North, similar to programs that offer loan forgiveness to work in remote locations.

Brant-Birioukov is from Tyendinaga, a First Nation roughly between Toronto and Ottawa. She thinks one of the most damaging impacts on First Nation students is high teacher turnover.

Teachers might often be less experienced or perhaps they do not have the cultural knowledge and expertise needed to teach in a culturally appropriate way, she explained.

Indigenizing the curriculum

Canada’s National Observer also investigated how the current curriculum does not adequately reflect the culture and celebrate Indigenous forms of education.

For example, Brant-Birioukov points to standardized testing to show how a curriculum can marginalize First Nation students. Questions might refer to going to restaurants or to the movies. But for Brant-Birioukov, it goes deeper: school curriculum emphasizes universal truth grounded in western science. That form of education can devalue a student’s own culture and tradition and open a void in a student’s identity.

It was similar for Cassandra Spade, a young Anishinaabe language learner, who felt her identity was obscured. Like a smudged mirror, she couldn’t see herself in the languages she was learning or articulate who she was until she studied Anishinaabemowin in an immersion program.

However, currently some northern First Nations lack an immersion program for their languages and are required to hire language teachers who have teaching certificates. Language teachers without a certificate are paid less and “so it’s a matter of that pay differential as well,” Brant-Birioukov said.

Also missing from First Nations’ curriculum is land-based education, a catch-all term for practices learned on the land: like how to harvest sap for maple syrup, clean an animal, prepare a hide or set a trap.

Sol Mamakwa, Ontario NDP MPP for Kiiwetinoong and once the education director in his community of Kingfisher Lake First Nation, envisions reforms to First Nation education by being on the land — learning numeracy through counting geese, and literacy through a student’s own language.

“I think as First Nation Anishinaabeg, we cannot just learn … about who we are in the four walls,” Mamakwa, said during a keynote speech to Indigenous students in March.

Comments

Once again, thank you. This is also my first experience with the trying to share a news story on Facebook, and having it blocked by: "Error. News content can't be shared in Canada: In response to Canadian government legislation, news content can’t be shared." Alarming. Any ideas on how I can share this information? Thank you.

Email several friends with it, ask for replies: do they want to keep getting stuff like that? Would they send it on in turn? Maybe few of the people who read your page were taking it in, anyway: now you'll know, and know which.