The Haida language is here to stay

A look inside the Skidegate Haida Immersion Program

Story by Emilee Gilpin

As politicians argue over pipelines and nuclear warfare, fear not. In many corners of the world, people are working tirelessly to learn land-based languages old as time, remembering, reawakening and revitalizing alternative ways forward.

In Haida Gwaii, an archipelago off the northwest coast of British Columbia, many indomitable spirits and multi-layered moving parts are tending to the fire of the Haida language. From the Skidegate Haida Immersion Program, which connects elders to state-of-the-art technology, to a team of hardworking teachers in Masset, the Haida's approach to language revitalization sets an example for Indigenous communities worldwide.

X̱aad kil/X̱aayda Kil (the Haida language) is not extinct and it is not dying. The Haida are using every tool available to cradle the gifts of their fluent speakers, semi-fluent speakers and silent speakers (those who understand, but don't speak the language), and pass them on to the generations hungry for a culture that has sustained their people since time immemorial.

X̱aad kil/X̱aayda kil is alive

An eagle rests on the eastern coast of Haida Gwaii. Photo by Mary Helmer

Sometimes the line between fiction and reality is blurry, if not utterly unbelievable.

The fictitious story about the history of Canada is much easier to stomach than the reality of how this country came to be. The colonial government's attempt to eradicate Indigenous cultures was multi-pronged - family bonds were progressively broken, systems of governance prohibited, and languages forbidden.

The Haida were no exception to the stretch of colonial conquest. Before this era, the Haida, in tens of thousands, populated all islands in the archipelago. Over time, the Haida congregated to three communities, one in southeastern Alaska, and the other two in Haida Gwaii, one in Old Masset (on the north end of the island of Haida Gwaii) and one in Skidegate (on the south end of the island).

Language is at the heart of a culture.

As Indigenous nations revitalize cultures carefully preserved and protected, language necessarily rests at the heart of these efforts. Language revitalization looks different for every community. Support for language programs and projects in B.C. comes primarily from the First Peoples' Cultural Council (FPCC), a First Nations-run Crown corporation responsible for distributing funds to support the 34 Indigenous languages in the province.

British Columbia is a hotbed for linguistic and cultural diversity, home to 60 per cent of the Indigenous languages spoken in Canada. To account for this diversity, the FPCC works with language experts from each community to determine what approaches work best for their language objectives. The provincial government recently announced $50 million towards Indigenous languages, some of which will go towards supporting initiatives in Haida Gwaii.

The Haida language was once spoken in more than 30 different dialects, across all islands. Today, there are three remaining dialects.

Skidegate and Old Masset have each created programs to keep the language of the land alive. Many have called Indigenous languages extinct, in a critical state, dead or dying, but there is spirit and life to the revitalization of X̱aad kil/X̱aayda kil that is undeniable. It is an inspiring and powerful force and one that has existed in the Haida people since time immemorial.

Language revitalization in Masset

Students in a Haida language class in 2016 gather seaweed during a field trip. Photo by Jaskwaan Bedard.

If Haida teachers made one thing clear, it's that they're just today's part of generations dedicated to the well-being of the Haida language.

Kwiiagee iiwaaans (Maureen) LaGroix has been teaching the Haida language in Old Masset for many years. Her name, Kwiiagee iiwaaans, means "precious one." She currently teaches at Guudangee Tlaatsgaa Naay "Strong Minded House," in Gaw (Old Masset).

LaGroix thinks herself lucky. When she was a child, she lived with her grandmother, who spoke only Haida and didn't allow English in the home.

"I was taken away when she passed," she said over the phone, "and as time went on, I didn't get to hear as much of it and my language disappeared."

In 1982, LaGroix was hired to work in an elementary school in Old Masset. She spent two and a half years learning a Haida writing system developed by linguist John Enrico. A lot of the work Haida language teachers did at that time, she said, was accomplished with few resources. LaGroix stayed in the elementary school for 10 years, then got her teaching degree, came home and worked for the band for seven years.

One of the lessons LaGroix wants to pass on now to language teachers and learners, is to not waste time trying to talk to kids about English grammar, or trying to translate English into Haida.

"It just takes forever," LaGroix stressed. "It's not working and it hasn't worked all this time. Our language isn't the same as English. You spend most of your time trying to figure out what all the terms are to make it Haida, and you run out of time. Our language is so different."

LaGroix said the best approach to teaching the language is utilizing a methodology relevant to one's daily life. People call it immersion, she said, but she prefers the words of an elder who once told her, "You'll never get anywhere, unless the language is used with what you're doing right now."

It has to be a part of your natural environment, she said, and can't be set up, like in a classroom. LaGroix thought about how her community would travel to different places throughout the changing seasons – gathering fish, harvesting food and moving with the language.

"It was a living spoken language," she said.

"When they took away those fish camps, where all the families worked together to get things done, they lost a lot of the family unit, but they also lost a lot of the connection to everyday language."

The language has to have meaning, she said, otherwise you'll forget it.

Eventually, LaGroix started to have high school students show up at her house at night. They wanted to continue learning the language, outside of the classroom. A hereditary chief also approached her. He was a silent speaker who understood a lot of the language, but he wanted to do his introduction using high-ranking Haida. Inspired by the interest, LaGroix started giving weekly classes from her home, first Thursdays, then Sundays, then whenever you could find the time.

LaGroix is grateful for the foresight of her grandmother, who would whack them every time they spoke English.

"How good of her to do that," she said.

Everything is connected to everything else

Jaskwaan (Amanda) Bedard was recently hired in Masset as the Haida language and culture curriculum teacher. The position was advertised in December last year, the same month she finished a teaching certification program through Simon Fraser University.

Bedard is also a board member for the First Peoples' Cultural Council (FPCC) and a part of the Haida Gwaii Master Apprentice Committee. She completed the Mentor-Apprenticeship Program through the FPCC.

"The apprenticeship program is a proven method for Indigenous language revitalization," Bedard said over the phone. The program matches fluent speakers with learners for a one-on-one immersion experience over a number of years. Bedard worked with Haida elder Primrose Adams for three years.

Last year, the Haida Gwaii Mentor-Apprentice Committee was born. The first session accepted three people from Masset and three from Skidegate, but this year, there was an influx of applicants – 13 from Masset and 10 from Skidegate.

"We altered it to be a semester program," Bedard said, "because we wanted to say yes to everybody."

Now, it won't be one-on -one, but two to three language learners will work with one master. That's what has to be done, she said, to make the language accessible to all people who want to learn.

Bedard also commended the language program at the Chief Matthews School in Old Masset. The program is taught by Kaayhlt’aa Xuhl (Rhonda) Bell, one of the youngest fluent speakers in Gaw.

Recently, the Integrated Resource Package, a compilation of instruction and resources for teachers implementing Haida language classes into their curriculum, has been approved by the government. The Haida language will now be implemented in schools in the north and south of Haida Gwaii. Bedard commended other language teachers in Masset, like Candace Weir-White, Maureen Brown, Rhonda Bell, and others, saying that nothing has been achieved without the efforts of many moving parts.

On top of Haida language class on island, those interested in learning the language can also access online resources, like the Skidegate Haida language app, and classes offered at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, including a postgraduate program in language revitalization. People in the community can work towards a language proficiency certificate, or choose to participate in one of the language nest programs (young families learn in an immersive setting together) – there are multiple avenues available for those who want to learn.

For Bedard, who says learning her language has helped her learn about herself, nurturing the Haida language is invaluable.

"Everything is connected to everything else," she said. "The strength of Indigenous peoples speaking the language of the land contributes to the strength of humanity."

Some have taken a different approach to preserving and sharing the Haida language, outside of the classroom. Brothers Gwaai and Jaalen Edenshaw, with musician Kinnie Starr and others, have created stop-motion videos and music videos. These shorts have in many ways set the stage for the full-length feature film, Edge of the Knife, a film produced entirely in the Haida language. The brothers wrote the script for the film along with Graham Richard.

The Edge of the Knife is a collaboration by the Haida Nation and producer Jonathan Frantz who works for the Inuit company Kingulliit Productions. Franz has worked closely with director Zacharias Kunuk, who directed Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. Unlike many feature films that portray Indigenous stories through the eyes of an outsider, Atanarjuat was an example of a traditional Inuit story portrayed by an entirely Inuit cast, through the direction of Inuit filmmakers.

Gwaai Edenshaw co-directed Edge of the Knife with Helen Haig-Brown, a Tsilhqot'in filmmaker. The entire cast, and as many of the production team as possible, were Haida. Community members went through an intensive Haida language immersion program to learn their lines.

In a video posted on the film's Facebook page, Gwaii called Edge of the Knife a "homegrown movie."

"It's not outsiders coming in and telling our story," he said. "It'll be a chance for us to be telling our own story."

Bedard said the film is an incredible example of the three Haida communities in Alaska, Masset and Skidegate, coming together with a common goal. She said it is powerful for their children and coming generations to have access to a film entirely in their language. The Edge of the Knife will be released this May.

The Skidegate Haida Immersion Program

Dii gway (bingo), "flirty Friday" lessons and weekly lunches are some of the activities that take place in the Long House Iitl'lxid Naay (the House of Chiefs) in the village of Skidegate.

The Skidegate Haida Immersion Program (SHIP) was founded in 1998, after an extremely impactful and successful 10-day Haida immersion summer session, with more than 40 students and 16 fluent teachers.

The language immersion program is based out of Iitl'lxid Naay (House of Chiefs) in HlGaagilda (Skidegate). As written in That Which Makes us Haida: The Haida Language – an astounding book documenting Haida language efforts – the philosophy behind SHIP is to make the program "everything that residential school wasn't."

For the first 11 years, the program was run by GwaaGanad (Diane Brown) and Luu Gaahlandaay (Kevin Borserio), but, due to funding cuts, Luu began to run the program alone. Funding is administered through the Skidegate Band Council, the school district and various project grants, but the majority of the time and energy dedicated to the program has been entirely voluntary.

The program is unique. Elders are connected to top-of-the-line technology, given headphones for hearing, microphones for recording and incentives to participate in what feels more like a family than a class.

Over the 20 years, SHIP has lost many beloved elders, including nine fluent speakers. The program started with 18 fluent speakers. Portraits of past participants are painted across the walls of the building. Today, the program is home to nine fluent speakers that attend regularly, with an average age of 80. A handful of silent speakers and learners come and go.

The program operates Monday to Friday from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. Participants are welcome for part-time classes, full-time classes, or to drop in and attend whenever possible. It is open to anyone with a heart open to learning the Skidegate Haida language, and elders instruct on a rotational basis.

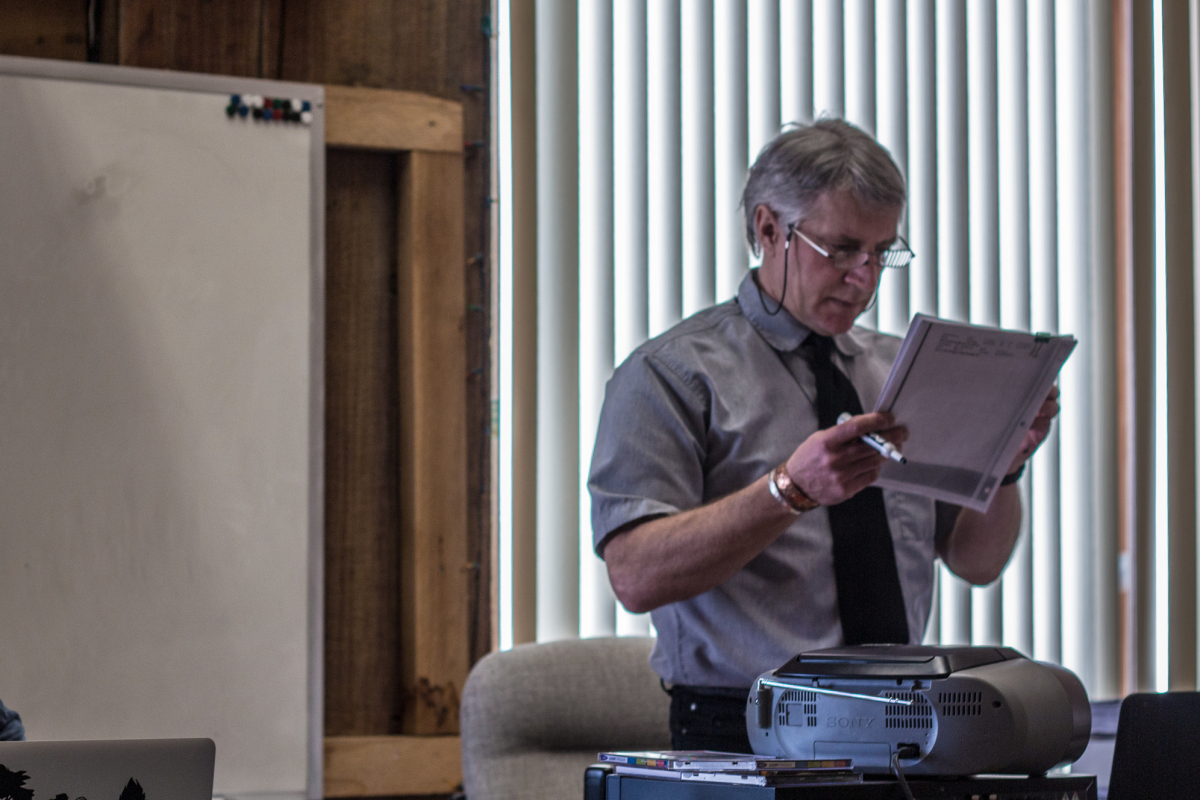

Kevin Borserio (known as Luu), is a non-Haida person, but has been working with the program since the beginning. Today, he is SHIP's primary facilitator. He has become semi-fluent in the Skidegate Haida dialect. In an interview for the book, That Which Makes us Haida, Borserio described his position as a "great privilege," and the Haida elders he works with as "heroes and family."

"Their language is a sound of beauty," he said. "It conveys deep and vivid connections to the earth, her people, the ocean and all creatures."

"We do a lot of documentation work," Borserio said, as the class settled in one Friday morning. "We have binders full of translation requests from the community and the Nation. Sometimes an elder will request that we translate a story or song, and we'll stop what we're doing and do that."

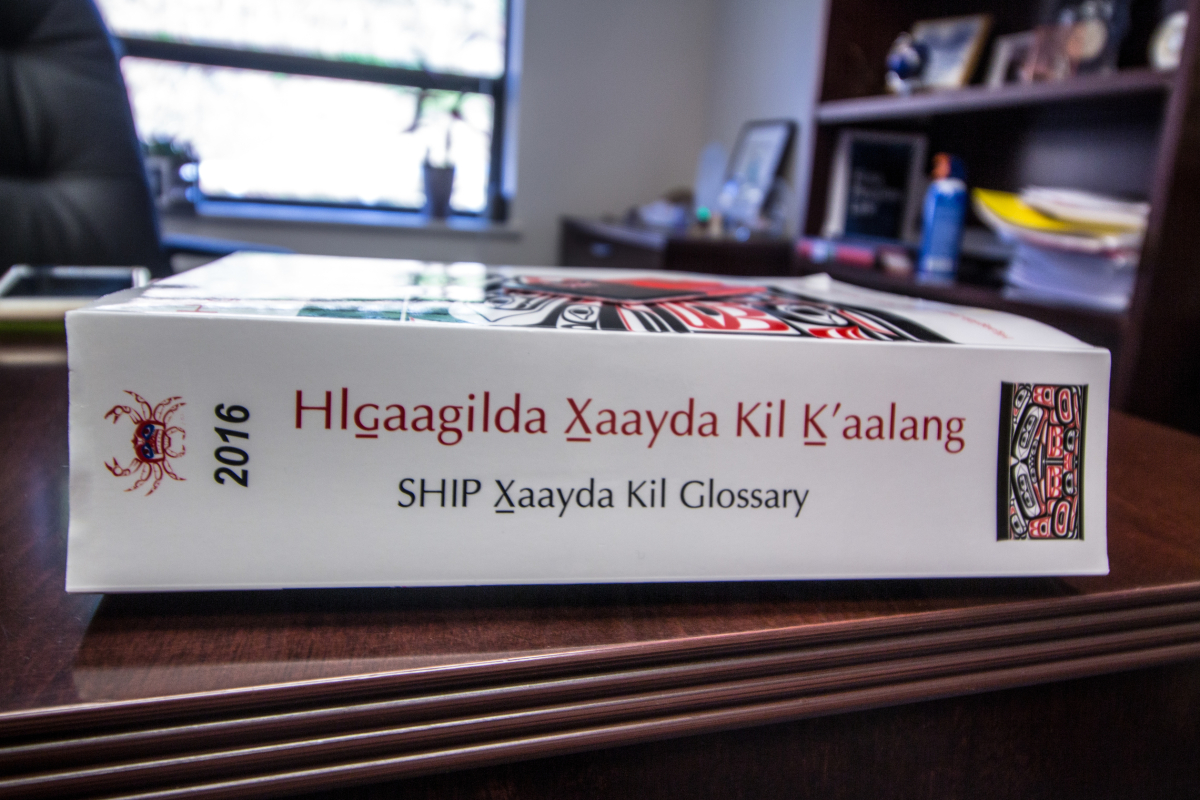

The SHIP program has produced over 240 instructional CDs for use in the program, in schools, at home, and for Haida living off-island. SHIP has also documented more than 11,000 words in a glossary published in 2016 – a glossary 20 years in the making.

"This glossary is all the work of these elders," Borserio said, holding up the thick white book. "Thirty thousand words in here that we have been documenting since 1998. The faces on the walls started all that work."

The class is working on prayer projects, a flirtation project (they call Friday afternoons, which are all about flirting in Haida, "flirty Fridays"), and a cook-book. They are translating stories from the Masset dialect into the Skidegate dialect and working for White Raven Law on reinstating Haida traditional knowledge to be used in the Haida title case launched in 2002.

The maps, pinned up on the large wooden walls of the building are another success story from the SHIP program. At least 3-4 months of ten of the last 20 years were spent working on maps.

Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Parks Canada paid for the SHIP group to go out on a sailboat for 14 days. The elders circumnavigated Gwaii Haanas, recalling traditional place names and recording them on new maps of their territories. Elders remembered traveling their territories as children, the names they knew and called back. The maps are a historic piece of work.

On Wednesdays, lunch is served, which usually includes salmon, halibut, chowder, herring eggs and bannock. A team of volunteers, directed by Elder Jixa (Gladys) Vandal, prepares, cooks and serves the food, welcoming community members to come by and share.

The SHIP program is well known and loved in the community. Visitors often drop in to share news, see what's going on with the elders and lend a hand in any way possible. Through their collaboration with certain partners, the elders were recently able to go on a group trip to Hawai'i, where they visited Hawaiian language schools. SHIP's monthly newsletter said the experience of Hawaiian students and staff speaking to them only in their Hawaiian language was the highlight of their trip.

Billy Yovanovich, chief of the Skidegate Band Council, said the SHIP program intends to take care of the community's elders. It gives them a place to go, keeps them active, walking to and from the building, and gives them something to focus their time and intention on, he explained on the way to one Wednesday lunch of halibut chowder.

That Which Makes Us Haida

Late Stephen Brown. Photo by Farah Nosh

While this story is meant to share a glimpse of current Haida language revitalization efforts, a book published in 2011 expands extensively on these efforts, as only community members themselves really could.

That Which Makes Us Haida was published by the Haida Gwaii Museum Press. It was curated by Jaskwaan (Amanda) Bedard and Nika Collison, edited by Scott Steedman and Collison, and includes forewords by Guujaaw and Wade Davis.

The book touches on the unique history of the Haida language and profiles elders in Alaska, Masset and Skidegate, sharing some of their stories and experiences speaking and preserving their precious language and interconnected culture.

The pages come to life with striking photographs by Farah Nosh, a photographer that has spent ample time on Haida Gwaii, photographing the community. The book also includes a CD with three Haida stories and three songs.

Collison is the executive director and curator at the Haida Gwaii Museum. In her opening statement of the book, she said Xaayda kil/Xaad kil is not just a language, but a different way of thinking.

"It is Haida knowledge, history and wisdom stores," she wrote. "It defines our intrinsic relationship to the lands, waters, airways and Supernatural Beings of Haida Gwaii: that which makes us Haida."

The book was an attempt to document stories and struggles, and honour of those who have worked to keep the Haida language alive. It is a testament to their service and another powerful part of how the heart of the Haida language beats.